Issues Identified by Postdischarge Contact after Pediatric Hospitalization: A Multisite Study

BACKGROUND: Many hospitals are considering contacting hospitalized patients soon after discharge to help with issues that arise.

OBJECTIVES: To (1) describe the prevalence of contact-identified postdischarge issues (PDI) and (2) assess characteristics of children with the highest likelihood of having a PDI.

DESIGN, SETTING, AND PATIENTS: A retrospective analysis of hospital-initiated follow-up contact for 12,986 children discharged from January 2012 to July 2015 from 4 US children’s hospitals. Contact was made within 14 days of discharge by hospital staff via telephone call, text message, or e-mail. Standardized questions were asked about issues with medications, appointments, and other PDIs. For each hospital, patient characteristics were compared with the likelihood of PDI by using logistic regression.

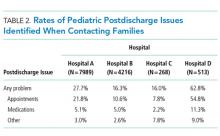

RESULTS: Median (interquartile range) age of children at admission was 4.0 years (0-11); 59.9% were non-Hispanic white, and 51.0% used Medicaid. The most common reasons for admission were bronchiolitis (6.3%), pneumonia (6.2%), asthma (5.1%), and seizure (4.9%). Twenty-five percent of hospitalized children (n = 3263) reported a PDI at contact (hospital range: 16.0%-62.8%). Most (76.3%) PDIs were related to follow-up appointments (eg, difficulty getting one); 20.8% of PDIs were related to medications (eg, problems filling a prescription). Patient characteristics associated with the likelihood of PDI varied across hospitals. Older age (age 10-18 years vs <1 year) was significantly (P < .001) associated with an increased likelihood of PDI in 3 of 4 hospitals.

CONCLUSIONS: PDIs were identified often through hospital-initiated follow-up contact. Most PDIs were related to appointments. Hospitals caring for children may find this information useful as they strive to optimize their processes for follow-up contact after discharge.

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

Clinical characteristics included a count of the different classes of medications (eg, antibiotics, antiepileptic medications, digestive motility medications, etc.) administered to the child during admission, the type and number of chronic conditions, and assistance with medical technology (eg, gastrostomy, tracheostomy, etc.). Except for medications, these characteristics were assessed with International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision-Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis codes.

We used the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Chronic Condition Indicator classification system, which categorizes over 14,000 ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes into chronic versus nonchronic conditions to identify the presence and number of chronic conditions.12 Children hospitalized with a chronic condition were further classified as having a complex chronic condition (CCC) by using the ICD-9-CM diagnosis classification scheme of Feudtner et al.13 CCCs represent defined diagnosis groupings of conditions expected to last longer than 12 months and involve either multiple organ systems or a single organ system severely enough to require specialty pediatric care and hospitalization.13,14 Children requiring medical technology were identified by using ICD-9-CM codes indicating their use of a medical device to manage and treat a chronic illness (eg, ventricular shunt to treat hydrocephalus) or to maintain basic body functions necessary for sustaining life (eg a tracheostomy tube for breathing).15,16

Statistical Analysis

Given that the primary purpose for this study was to leverage the natural heterogeneity in the approach to follow-up contact across hospitals, we assessed and reported the prevalence and type of PDIs independently for each hospital. Relatedly, we assessed the relationship between patient characteristics and PDI likelihood independently within each hospital as well rather than pool the data and perform a central analysis across hospitals. Of note, APR-DRG and medication class were not assessed for hospital D, as this information was unavailable. We used χ2 tests for univariable analysis and logistic regression with a backwards elimination derivation process (for variables with P ≥ .05) for multivariable analysis; all patient demographic, clinical, and hospitalization characteristics were entered initially into the models. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), and P < .05 was considered statistically significant. This study was approved by the institutional review board at all hospitals.

RESULTS

Study Population

There were 12,986 (51.4%) of 25,259 patients reached by follow-up contact after discharge across the 4 hospitals. Median age at admission for contacted patients was 4.0 years (interquartile range [IQR] 0-11). Of those contacted, 45.2% were female, 59.9% were non-Hispanic white, 51.0% used Medicaid, and 95.4% were discharged to home. Seventy-one percent had a chronic condition (of any complexity) and 40.8% had a CCC. Eighty percent received a prescribed medication during the hospitalization. Median (IQR) length of stay was 2.0 days (IQR 1-4 days). The top 5 most common reasons for admission were bronchiolitis (6.3%), pneumonia (6.2%), asthma (5.2%), seizure (4.9%), and tonsil and adenoid procedures (4.1%).

PDIs

Characteristics Associated with PDIs

Age

Older age was a consistent characteristic associated with PDIs in 3 hospitals. For example, PDI rates in children 10 to 18 years versus <1 year were 30.8% versus 21.4% (P < .001) in hospital A, 19.4% versus 13.7% (P = .002) in hospital B, and 70.3% versus 62.8% (P < .001) in hospital D. In multivariable analysis, age 10 to 18 years versus <1 year at admission was associated with an increased likelihood of PDI in hospital A (odds ratio [OR] 1.7; 95% CI, 1.4-2.0), hospital B (OR 1.4; 95% CI, 1.1-1.8), and hospital D (OR 1.7; 95% CI, 0.9-3.0) (Table 3 and Figure).