Patterns and Predictors of Short-Term Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter Use: A Multicenter Prospective Cohort Study

BACKGROUND: The guidelines for peripherally inserted central catheters (PICCs) recommend avoiding insertion if the anticipated duration of use is ≤5 days. However, short-term PICC use is common in hospitals. We sought to identify patient, provider, and device characteristics and the clinical outcomes associated with short-term PICCs.

METHODS: Between January 2014 and June 2016, trained abstractors at 52 Michigan Hospital Medicine Safety (HMS) Consortium sites collected data from medical records of adults that received PICCs during hospitalization. Patients were prospectively followed until PICC removal, death, or 70 days after insertion. Multivariable logistic regression models were fit to identify factors associated with short-term PICCs, defined as dwell time of ≤5 days. Complications associated with short-term use, including major (eg, venous thromboembolism [VTE] or central line-associated bloodstream infection [CLABSI]) or minor (eg, catheter occlusion, tip migration) events were assessed.

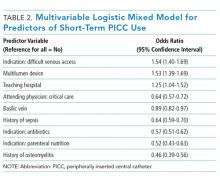

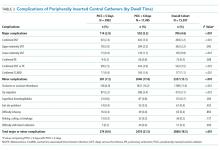

RESULTS: Of the 15,397 PICCs placed, 3902 (25.3%) had a dwell time of ≤5 days. Most (95.5%) short-term PICCs were removed during hospitalization. Compared to PICCs placed for >5 days, variables associated with short-term PICCs included difficult venous access (odds ratio [OR], 1.54; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.40-1.69), multilumen devices (OR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.39-1.69), and teaching hospitals (OR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.04-1.52). Among those with short-term PICCs, 374 (9.6%) experienced a complication, including 99 (2.5%) experiencing VTE and 17 (0.4%) experiencing CLABSI events. The most common minor complications were catheter occlusion (4%) and tip migration (2.2%).

CONCLUSION: Short-term use of PICCs is common and associated with patient, provider, and device factors. As PICC placement, even for brief periods, is associated with complications, efforts targeted at factors underlying such use appear necessary.

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

Among short-term PICCs, 3618 (92.7%) were power-capable devices, 2785 (71.4%) were 5-French, and 2813 (72.1%) were multilumen. Indications for the use of short-term PICCs differed from longer term devices in important ways (P < .001). For example, the most common documented indication for short-term PICC use was difficult venous access (28.2%), while for long-term PICCs, it was antibiotic administration (39.8%). General internists and hospitalists were the most common attending physicians for patients with short-term and long-term PICCs (65.1% and 65.5%, respectively [P = .73]). Also, the proportion of critical care physicians responsible for patients with short versus long-term PICC use was similar (14.0% vs 15.0%, respectively [P = .123]). Of the short-term PICCs, 2583 (66.2%) were inserted by vascular access nurses, 795 (20.4%) by interventional radiologists, and 439 (11.3%) by advance practice professionals. Almost all of the PICCs placed ≤5 days (95.5%) were removed during hospitalization.

Complications Associated with Short-Term Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter Use

DISCUSSION

This large, multisite prospective cohort study is the first to examine patterns and predictors of short-term PICC use in hospitalized adults. By examining clinically granular data derived from the medical records of patients across 52 hospitals, we found that short-term use was common, representing 25% of all PICCs placed. Almost all such PICCs were removed prior to discharge, suggesting that they were placed primarily to meet acute needs during hospitalization. Multivariable models indicated that patients with difficult venous access, multilumen devices, and teaching hospital settings were associated with short-term use. Given that (a) short term PICC use is not recommended by published evidence-based guidelines,12,13 (b) both major and minor complications were not uncommon despite brief exposure, and (c) specific factors might be targeted to avoid such use, strategies to improve PICC decision-making in the hospital appear increasingly necessary.

In our study, difficult venous access was the most common documented indication for short-term PICC placement. For patients in whom an anticipated catheter dwell time of 5 days or less is expected, MAGIC recommends the consideration of midline or peripheral IV catheters placed under ultrasound guidance.12 A midline is a type of peripheral IV catheter that is about 7.5 cm to 25 cm in length and is typically inserted in the larger diameter veins of the upper extremity, such as the cephalic or basilic veins, with the tip terminating distal to the subclavian vein.7,12 While there is a paucity of information that directly compares PICCs to midlines, some data suggest a lower risk of bloodstream infection and thrombosis associated with the latter.24-26 For example, at one quaternary teaching hospital, house staff who are trained to insert midline catheters under ultrasound guidance in critically ill patients with difficult venous access reported no CLABSI and DVT events.26

Interestingly, multilumen catheters were used twice as often as single lumen catheters in patients with short-term PICCs. In these instances, the use of additional lumens is questionable, as infusion of multiple incompatible fluids was not commonly listed as an indication prompting PICC use. Because multilumen PICCs are associated with higher risks of both VTE and CLABSI compared to single lumen devices, such use represents an important safety concern.27-29 Institutional efforts that not only limit the use of multilumen PICCs but also fundamentally define when use of a PICC is appropriate may substantially improve outcomes related to vascular access.28,30,31We observed that short-term PICCs were more common in teaching compared to nonteaching hospitals. While the design of the present study precludes understanding the reasons for such a difference, some plausible theories include the presence of physician trainees who may not appreciate the risks of PICC use, diminishing peripheral IV access securement skills, and the lack of alternatives to PICC use. Educating trainees who most often order PICCs in teaching settings as to when they should or should not consider this device may represent an important quality improvement opportunity.32 Similarly, auditing and assessing the clinical skills of those entrusted to place peripheral IVs might prove helpful.33,34 Finally, the introduction of a midline program, or similar programs that expand the scope of vascular access teams to place alternative devices, should be explored as a means to improve PICC use and patient safety.

Our study also found that a third of patients who received PICCs for 5 or fewer days had moderate to severe chronic kidney disease. In these patients who may require renal replacement therapy, prior PICC placement is among the strongest predictors of arteriovenous fistula failure.35,36 Therefore, even though national guidelines discourage the use of PICCs in these patients and recommend alternative routes of venous access,12,37,38 such practice is clearly not happening. System-based interventions that begin by identifying patients who require vein preservation (eg, those with a GFR < 45 ml/min) and are therefore not appropriate for a PICC would be a welcomed first step in improving care for such patients.37,38Our study has limitations. First, the observational nature of the study limits the ability to assess for causality or to account for the effects of unmeasured confounders. Second, while the use of medical records to collect granular data is valuable, differences in documentation patterns within and across hospitals, including patterns of missing data, may produce a misclassification of covariates or outcomes. Third, while we found that higher rates of short-term PICC use were associated with teaching hospitals and patients with difficult venous access, we were unable to determine the precise reasons for this practice trend. Qualitative or mixed-methods approaches to understand provider decision-making in these settings would be welcomed.

Our study also has several strengths. First, to our knowledge, this is the first study to systematically describe and evaluate patterns and predictors of short-term PICC use. The finding that PICCs placed for difficult venous access is a dominant category of short-term placement confirms clinical suspicions regarding inappropriate use and strengthens the need for pathways or protocols to manage such patients. Second, the inclusion of medical patients in diverse institutions offers not only real-world insights related to PICC use, but also offers findings that should be generalizable to other hospitals and health systems. Third, the use of a robust data collection strategy that emphasized standardized data collection, dedicated trained abstractors, and random audits to ensure data quality strengthen the findings of this work. Finally, our findings highlight an urgent need to develop policies related to PICC use, including limiting the use of multiple lumens and avoidance in patients with moderate to severe kidney disease.

In conclusion, short-term use of PICCs is prevalent and associated with key patient, provider, and device factors. Such use is also associated with complications, such as catheter occlusion, tip migration, VTE, and CLABSI. Limiting the use of multiple-lumen PICCs, enhancing education for when a PICC should be used, and defining strategies for patients with difficult access may help reduce inappropriate PICC use and improve patient safety. Future studies to examine implementation of such interventions would be welcomed.