Morbo Serpentino

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

Metastatic cancer, including lymphoma, could cause pulmonary and cutaneous nodules and liver involvement, but the chronic time course and uveitis are not consistent with malignancy. Tuberculosis is still a consideration, though one would have expected him to report fevers, night sweats, and, perhaps, exposure to patients with pulmonary tuberculosis in his job as a nurse. Multiple solid pulmonary nodules are also uncommon with pulmonary tuberculosis. Fungal infections such as histoplasmosis can cause skin lesions and pulmonary nodules but do not fit well with uveitis.

At this point, “ tissue is the issue.” A skin nodule would be the easiest site to biopsy. If skin biopsy was not diagnostic, computed tomography (CT) of his chest and abdomen should be performed to identify the next most accessible site for biopsy.

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) and colonoscopy showed normal findings, and random biopsies from the stomach and colon were normal. CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis performed with the administration of intravenous contrast showed multiple solid opacities in both lung fields up to 1 cm, with enlarged mediastinal and retroperitoneal lymph nodes measuring 1 to 3 cm in diameter, a left pleural effusion, wall thickening in the right colon, and several nonspecific hypodensities in the liver. A punch biopsy taken from the right chest wall lesion demonstrated chronic inflammation without granulomas. The patient underwent CT-guided biopsy of 1 of the right-sided lung nodules, which revealed noncaseating granulomatous inflammation, fibrosis, and necrosis. Neither biopsy contained malignant cells, and additional stains revealed no bacteria, fungi, or acid fast bacilli.

The retroperitoneal and mediastinal adenopathy are indicative of a widely disseminated inflammatory process. Lymphoma continues to be a concern, though uveitis as an initial presenting problem would very unusual. Although biopsy of the chest wall lesion failed to demonstrate granulomatous inflammation, the most parsimonious explanation is that the skin and lung nodules are both related to a single systemic process.

Granulomas form in an attempt to wall off offending agents, whether foreign antigens (talc, certain medications), infectious agents, or self-antigens. Review of histopathology and microbiologic studies are useful first steps. Stains for bacteria, fungi, or acid-fast organisms may diagnose an infectious cause, such as tuberculosis, leprosy, syphilis, fungi, or cat scratch disease. Granulomas in association with vascular inflammation would indicate vasculitis. Other autoimmune considerations include sarcoidosis and Crohn disease. Noncaseating granulomas are typically found in sarcoidosis, cat scratch disease, syphilis, leprosy, or Crohn disease, but do not entirely exclude tuberculosis.

The negative infectious studies and lack of classic features of Crohn disease or other autoimmune diseases further point to sarcoidosis as the etiology of this patient’s illness. A Norwegian dermatologist first described the pathology of sarcoidosis based upon specimens taken from skin nodules. He thought the lesions were sarcoma and described them as, “ multiple benign sarcoid of the skin,” which is where the name “ sarcoidosis” originated.

Diagnosing sarcoidosis requires excluding other mimickers. Additional testing should include syphilis serologies, rheumatoid factor, and antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibodies. The latter is associated with granulomatosis with polyangiitis and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, either of which may produce granulomatous inflammation of the lungs, skin, and uvea.

At this juncture, PET-CT represents a costly and unnecessary test that does not narrow our diagnostic possibilities sufficiently to justify its use. Osteolytic lesions would be unusual in sarcoidosis and more likely in lymphoma or infectious processes such as tuberculosis. Tests for syphilis and tuberculosis are required, and are a fraction of the cost of a PET-CT.

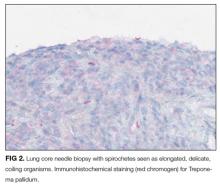

With the biopsy revealing spirochetes, and the positive results of a nontreponemal test (RPR) and confirmatory treponemal results, the diagnosis of syphilis is firmly established. Uveitis indicates neurosyphilis and warrants a longer course of intravenous penicillin. Lumbar puncture should be performed.

A lumbar puncture was performed. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) contained 9 white blood cells and 73 red blood cells per cubic milliliter; protein concentration was 73 mg/dL, and glucose was 116 mg/dL. Polymerase chain reaction for T. pallidum was negative. Transthoracic ECG and magnetic resonance imaging of the brain were normal. The patient was treated with intravenous penicillin G at 5 million units 4 times daily for 15 days. A PET-CT scan 3 months later revealed complete resolution of the subcutaneous, pulmonary, liver lesions, lymphadenopathy, and uveitis. Repeat treponemal serologies demonstrated a greater than 4-fold decline in titers.