Mass Confusion

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

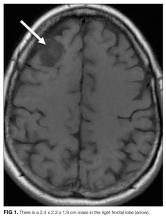

A 57-year-old woman presented to the emergency department of a community hospital with a 2-week history of dizziness, blurred vision, and poor coordination following a flu-like illness. Symptoms were initially attributed to complications from a presumed viral illness, but when they persisted for 2 weeks, she underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain, which was reported as showing a 2.4 x 2.3 x 1.9 cm right frontal lobe mass with mild mass effect and contrast enhancement (Figure 1). She was discharged home at her request with plans for outpatient follow-up.

Brain masses are usually neoplastic, infectious, or less commonly, inflammatory. The isolated lesion in the right frontal lobe is unlikely to explain her symptoms, which are more suggestive of multifocal disease or elevated intracranial pressure. Although the frontal eye fields could be affected by the mass, such lesions usually cause tonic eye deviation, not blurry vision; furthermore, coordination, which is impaired here, is not governed by the frontal lobe.

Two weeks later, she returned to the same emergency department with worsening symptoms and new bilateral upper extremity dystonia, confusion, and visual hallucinations. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis revealed clear, nonxanthochromic fluid with 4 nucleated cells (a differential was not performed), 113 red blood cells, glucose of 80 mg/dL (normal range, 50-80 mg/dL), and protein of 52 mg/dL (normal range, 15-45 mg/dL).

Confusion is generally caused by a metabolic, infectious, structural, or toxic etiology. Standard CSF test results are usually normal with most toxic or metabolic encephalopathies. The absence of significant CSF inflammation argues against infectious encephalitis; paraneoplastic and autoimmune encephalitis, however, are still possible. The CSF red blood cells were likely due to a mildly traumatic tap, but also may have arisen from the frontal lobe mass or a more diffuse invasive process, although the lack of xanthochromia argues against this. Delirium and red blood cells in the CSF should trigger consideration of herpes simplex virus (HSV) encephalitis, although the time course is a bit too protracted and the reported MRI findings do not suggest typical medial temporal lobe involvement.

The disparate neurologic findings suggest a multifocal process, perhaps embolic (eg, endocarditis), ischemic (eg, intravascular lymphoma), infiltrative (eg, malignancy, neurosarcoidosis), or demyelinating (eg, postinfectious acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, multiple sclerosis). However, most of these would have been detected on the initial MRI. Upper extremity dystonia would likely localize to the basal ganglia, whereas confusion and visual hallucinations are more global. The combination of a movement disorder and visual hallucinations is seen in Lewy body dementia, but this tempo is not typical.

Although the CSF does not have pleocytosis, her original symptoms were flu-like; therefore, CSF testing for viruses (eg, enterovirus) is reasonable. Bacterial, mycobacteria, and fungal studies are apt to be unrevealing, but CSF cytology, IgG index, and oligoclonal bands may be useful. Should the encephalopathy progress further and the general medical evaluation prove to be normal, then tests for autoimmune disorders (eg, antinuclear antibodies, NMDAR, paraneoplastic disorders) and rare causes of rapidly progressive dementias (eg, prion diseases) should be sent.

Additional CSF studies including HSV polymerase chain reaction (PCR), West Nile PCR, Lyme antibody, paraneoplastic antibodies, and cytology were sent. Intravenous acyclovir was administered. The above studies, as well as Gram stain, acid-fast bacillus stain, fungal stain, and cultures, were negative. She was started on levetiracetam for seizure prevention due to the mass lesion. An electroencephalogram (EEG) was reported as showing diffuse background slowing with superimposed semiperiodic sharp waves with a right hemispheric emphasis. Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) 0.4 mg/kg/day over 5 days was administered with no improvement. The patient was transferred to an academic medical center for further evaluation.

The EEG reflects encephalopathy without pointing to a specific diagnosis. Prophylactic antiepileptic medications are not indicated for CNS mass lesions without clinical or electrophysiologic seizure activity. IVIG is often administered when an autoimmune encephalitis is suspected, but the lack of response does not rule out an autoimmune condition.

Her medical history included bilateral cataract extraction, right leg fracture, tonsillectomy, and total abdominal hysterectomy. She had a 25-year smoking history and a family history of lung cancer. She had no history of drug or alcohol use. On examination, her temperature was 37.9°C, blood pressure of 144/98 mm Hg, respiratory rate of 18 breaths per minute, a heart rate of 121 beats per minute, and oxygen saturation of 97% on ambient air. Her eyes were open but she was nonverbal. Her chest was clear to auscultation. Heart sounds were distinct and rhythm was regular. Abdomen was soft and nontender with no organomegaly. Skin examination revealed no rash. Her pupils were equal, round, and reactive to light. She did not follow verbal or gestural commands and intermittently tracked with her eyes, but not consistently enough to characterize extraocular movements. Her face was symmetric. She had a normal gag and blink reflex and an increased jaw jerk reflex. Her arms were flexed with increased tone. She had a positive palmo-mental reflex. She had spontaneous movement of all extremities. She had symmetric, 3+ reflexes of the patella and Achilles tendon with a bilateral Babinski’s sign. Sensation was intact only to withdrawal from noxious stimuli.

The physical exam does not localize to a specific brain region, but suggests a diffuse brain process. There are multiple signs of upper motor neuron involvement, including increased tone, hyperreflexia, and Babinski (plantar flexion) reflexes. A palmo-mental reflex signifies pathology in the cerebrum. Although cranial nerve testing is limited, there are no features of cranial neuropathy; similarly, no pyramidal weakness or sensory deficit has been demonstrated on limited testing. The differential diagnosis of her rapidly progressive encephalopathy includes autoimmune or paraneoplastic encephalitis, diffuse infiltrative malignancy, metabolic diseases (eg, porphyria, heavy metal intoxication), and prion disease.