Impact of Displaying Inpatient Pharmaceutical Costs at the Time of Order Entry: Lessons From a Tertiary Care Center

BACKGROUND: A lack of cost-conscious medication use is a major contributor to excessive healthcare expenditures in the inpatient setting. Expensive medicines are often utilized when there are comparable alternatives available at a lower cost. Increasing prescriber awareness of medication cost at the time of ordering may help promote cost-conscious use of medications in the hospital.

OBJECTIVE: To evaluate the impact of cost messaging on the ordering of 9 expensive medications.

DESIGN: Retrospective analysis of an institutional cost-transparency initiative.

SETTING: A 1145-bed, tertiary care, academic medical center.

PARTICIPANTS: Prescribers who ordered medications through the computerized provider order entry system at the Johns Hopkins Hospital.

METHODS: Interrupted time series and segmented regression models were used to examine prescriber ordering before and after implementation of cost messaging for 9 high-cost medications.

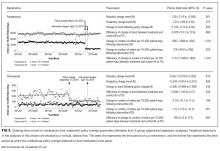

RESULTS: Following the implementation of cost messaging, no significant changes were observed in the number of orders or ordering trends for intravenous (IV) formulations of eculizumab, calcitonin, levetiracetam, linezolid, mycophenolate, ribavirin, and levothyroxine. An immediate and sustained reduction in medication utilization was seen in 2 drugs that underwent a policy change during our study, IV pantoprazole and oral voriconazole. IV pantoprazole became restricted at our facility due to a national shortage (–985 orders per 10,000 patient days; P < 0.001), and oral voriconazole was replaced with an alternative antifungal in oncology order sets (–110 orders per 10,000 patient days; P = 0.001).

CONCLUSIONS: Prescriber cost transparency alone did not significantly influence medication utilization at our institution. Active strategies to reduce ordering resulted in dramatic reductions in ordering. Journal of Hospital Medicine 2017;12: 639-645. © 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

Here, 3 coefficients were added (β4-β7) to describe an additional cohort of orders. Cohort, a binary indicator variable, held a value of either 0 or 1 when the model was used to describe the treatment or comparison group, respectively. The coefficients β4-β7 described the treatment group, and β0-β3 described the comparison group. β4 was the difference in the number of baseline orders per 10,000 patient days between treatment and comparison groups; Β5 represented the difference between the estimated ordering trends of treatment and comparison groups; and Β6 indicated the difference in immediate changes in the number of orders per 10,000 patient days in the 2 groups following the intervention.

The number of orders per week was recorded for each medicine, which enabled a large number of data points to be included in our analyses. This allowed for more accurate and stable estimates to be made in our regression model. A total of 143 data points were collected for each study group, 116 before and 27 following each intervention.

All analyses were conducted by using STATA version 13.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

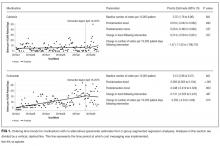

Initial results pertaining to 9 IV medications were examined (Table). Following the implementation of cost messaging, no significant changes were observed in order frequency or trend for IV formulations of eculizumab, calcitonin, levetiracetam, linezolid, mycophenolate, ribavirin, voriconazole, and levothyroxine (Figures 1 and 2). However, a significant decrease in the number of oral ribavirin orders (Figure 2), the control group for the IV form, was observed (–16.3 orders per 10,000 patient days; P = .004; 95% CI, –27.2 to –5.31).

DISCUSSION

Our results suggest that the passive strategy of displaying cost alone was not effective in altering prescriber ordering patterns for the selected medications. This may be due to a lack of awareness regarding direct financial impact on the patient, importance of costs in medical decision-making, or a perceived lack of alternatives or suitability of recommended alternatives. These results may prove valuable to hospital and pharmacy leadership as they develop strategies to curb medication expense.

Changes observed in IV pantoprazole ordering are instructive. Due to a national shortage, the IV form of this medication underwent a restriction, which required approval by the pharmacy prior to dispensing. This restriction was instituted independently of our study and led to a 73% decrease from usage rates prior to policy implementation (Figure 3). Ordering was restricted according to defined criteria for IV use. The restriction did not apply to oral pantoprazole, and no significant change in ordering of the oral formulation was noted during the evaluated period (Figure 3).

The dramatic effect of policy changes, as observed with pantoprazole and voriconazole, suggests that a more active strategy may have a greater impact on prescriber behavior when it comes to medication ordering in the inpatient setting. It also highlights several potential sources of confounding that may introduce bias to cost-transparency studies.

This study has multiple limitations. First, as with all observational study designs, causation cannot be drawn with certainty from our results. While we were able to compare medications to their preintervention baselines, the data could have been impacted by longitudinal or seasonal trends in medication ordering, which may have been impacted by seasonal variability in disease prevalence, changes in resistance patterns, and annual cycling of house staff in an academic medical center. While there appear to be potential seasonal patterns regarding prescribing patterns for some of the medications included in this analysis, we also believe the linear regressions capture the overall trends in prescribing adequately. Nonstationarity, or trends in the mean and variance of the outcome that are not related to the intervention, may introduce bias in the interpretation of our findings. However, we believe the parameters included in our models, namely the immediate change in the intercept following the intervention and the change in the trend of the rate of prescribing over time from pre- to postintervention, provide substantial protections from faulty interpretation. Our models are limited to the extent that these parameters do not account for nonstationarity. Additionally, we did not collect data on dosing frequency or duration of treatment, which would have been dependent on factors that are not readily quantified, such as indication, clinical rationale, or patient response. Thus, we were not able to evaluate the impact of the intervention on these factors.

Although intended to enhance internal validity, comparison groups were also subject to external influence. For example, we observed a significant, short-lived rise in oral ribavirin (a control medication) ordering during the preintervention baseline period that appeared to be independent of our intervention and may speak to the unaccounted-for longitudinal variability detailed above.

Finally, the clinical indication and setting may be important. Previous studies performed at the same hospital with price displays showed a reduction in laboratory ordering but no change in imaging.18,19 One might speculate that ordering fewer laboratory tests is viewed by providers as eliminating waste rather than choosing a less expensive option to accomplish the same diagnostic task at hand. Therapeutics may be more similar to radiology tests, because patients presumably need the treatment and often do not have the option of simply not ordering without a concerted effort to reevaluate the treatment plan. Additionally, in a tertiary care teaching center such as ours, a junior clinician, oftentimes at the behest of a more senior colleague, enters most orders. In an environment in which the ordering prescriber has more autonomy or when the order is driven by a junior practitioner rather than an attending (such as daily laboratories), results may be different. Additionally, institutions that incentivize prescribers directly to practice cost-conscious care may experience different results from similar interventions.

We conclude that, in the case of medication cost messaging, a strategy of displaying cost information alone was insufficient to affect prescriber ordering behavior. Coupling cost transparency with educational interventions and active stewardship to impact clinical practice is worthy of further study.