If You Book It, Will They Come? Attendance at Postdischarge Follow-Up Visits Scheduled by Inpatient Providers

BACKGROUND: Postdischarge follow-up visits (PDFVs) are widely recommended to improve inpatient-outpatient transitions of care.

OBJECTIVE: To measure PDFV attendance rates. DESIGN: Observational cohort study.

SETTING: Medical units at an academic quaternary-care hospital and its affiliated outpatient clinics.

PATIENTS: Adult patients hospitalized between April 2014 and March 2015 for whom at least 1 PDFV with our health system was scheduled. Exclusion criteria included nonprovider visits, visits cancelled before discharge, nonaccepted health insurance, and visits scheduled for deceased patients.

MEASUREMENTS: The study outcome was the incidence of PDFVs resulting in no-shows or same-day cancellations (NS/SDCs).

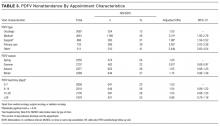

RESULTS: Of all hospitalizations, 6136 (52%) with 9258 PDFVs were analyzed. Twenty-five percent of PDFVs were NS/SDCs, 23% were cancelled before the visit, and 52% were attended as scheduled. In multivariable regression models, NS/SDC risk factors included black race (odds ratio [OR] 1.94, 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.63-2.32), longer lengths of stay (hospitalizations ≥15 days: OR 1.51, 95% CI, 1.22-1.88), and discharge to facility (OR 2.10, 95% CI, 1.70-2.60). Conversely, NS/SDC visits were less likely with advancing age (age ≥65 years: OR 0.39, 95% CI, 0.31-0.49) and driving distance (highest quartile: OR 0.65, 95% CI, 0.52-0.81). Primary care visits had higher NS/SDC rates (OR 2.62, 95% CI, 2.03-3.38) than oncologic visits. The time interval between discharge and PDFV was not associated with NS/SDC rates.

CONCLUSIONS: PDFVs were scheduled for more than half of hospitalizations, but 25% resulted in NS/SDCs. New strategies are needed to improve PDFV attendance. Journal of Hospital Medicine 2017;12:618-625. © 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

DISCUSSION

When comparing PDFV characteristics themselves, oncologic visits had the lowest NS/SDC incidence of any group analyzed in our study. This may be related to the inherent life-altering nature of a cancer diagnosis or our cancer center’s use of patient navigators.23,30 In contrast, primary care clinics suffered from NS/SDC rates approaching 40%, which is a concerning finding given the importance of primary care coordination in the posthospitalization period.9,31 Why are primary care appointments so commonly missed? Some studies suggest that forgetting about a primary care appointment is a leading reason.15,32,33 For PDFVs, this phenomenon may be augmented because the visits are not scheduled by patients themselves. Additionally, patients may paradoxically undervalue the benefit of an all-encompassing primary care visit, compared to a PDFV focused on a specific problem, (eg, a cardiology follow-up appointment for a patient with congestive heart failure). In particular, patients with limited health literacy may potentially undervalue the capabilities of their primary care clinics.34,35

The low absolute number of primary care PDFVs (only 8% of all visits) scheduled for patients at our hospital was an unexpected finding. This low percentage is likely a function of the patient population hospitalized at our large, urban quaternary-care facility. First, an unknown number of patients may have had PDFVs manually scheduled with primary care providers external to our health system; these PDFVs were not captured within our study. Second, 71% of the hospitalizations in our study occurred in subspecialty services, for which specific primary care follow-up may not be as urgent. Supporting this fact, further analysis of the 6136 hospitalizations in our study (data not shown) revealed that 28% of the hospitalizations in general internal medicine were scheduled with at least 1 primary care PDFV as opposed to only 5% of subspecialty-service hospitalizations.

In contrast to several previous studies of outpatient nonattendance,we did not find that visits scheduled for time points further in the future were more likely to be missed.14,24,25,36,37 Unlike other appointments, it may be that PDFV lead time does not affect attendance because of the unique manner in which PDFV times are scheduled and conveyed to patients. Unlike other appointments, patients do not schedule PDFVs themselves but instead learn about their PDFV dates as part of a large set of discharge instructions. This practice may result in poor recall of PDFV dates in recently hospitalized patients38, regardless of the lead time between discharge and the visit itself.

Supplementary Table 1 details a 51% NS/SDC rate for the small number of PDFVs (n = 65) that were excluded a priori from our analysis because of general ineligibility for UPHS outpatient care. We specifically chose to exclude this population because of the infrequent and irregular process by which these PDFVs were authorized on a case-by-case basis, typically via active engagement by our hospital’s social work department. We did not study this population further but postulate that the 51% NS/SDC rate may reflect other social determinants of health that contribute to appointment nonadherence in a predominantly uninsured population.

Beyond their effect on patient outcomes, improving PDFV-related processes has the potential to boost both inpatient and outpatient provider satisfaction. From the standpoint of frontline inpatient providers (often resident physicians), calling outpatient clinics to request PDFVs is viewed as 1 of the top 5 administrative tasks that interfere with house staff education.39 Future interventions that involve patients in the PDFV scheduling process may improve inpatient workflow while simultaneously engaging patients in their own care. For example, asking clinic representatives to directly schedule PDFVs with hospitalized patients, either by phone or in person, has been shown in pilot studies to improve PDFV attendance and decrease readmissions.40-42 Conversely, NS/SDC visits harm outpatient provider productivity and decrease provider availability for other patients.13,17,43 Strategies to mitigate the impact of unfilled appointment slots (eg, deliberately overbooking time slots in advance) carry their own risks, including provider burnout.44 As such, preventing NSs may be superior to curing their adverse impacts. Many such strategies exist in the ambulatory setting,13,43,45 for example, better communication with patients through texting or goal-directed, personalized phone reminders.46-48Our study methodology has several limitations. Most importantly, we were unable to measure PDFVs made with providers unaffiliated with UPHS. As previously noted, our low proportion of primary care PDFVs may specifically reflect patients with primary care providers outside of our health system. Similarly, our low percentage of Medicaid patients receiving PDFVs may be related to follow-up visits with nonaffiliated community health centers. We were unable to measure patient acuity and health literacy as potential predictors of NS/SDC rates. Driving distances were calculated from patient postal codes to our hospital, not to individual outpatient clinics. However, the majority of our hospital-affiliated clinics are located adjacent to our hospital; additionally, we grouped driving distances into quartiles for our analysis. We had initially attempted to differentiate between clinic-initiated and patient-initiated cancellations, but unfortunately, we found that the data were too unreliable to be used for further analysis (outlined in Supplementary Table 3). Lastly, because we studied patients in medical units at a single large, urban, academic center, our results are not generalizable to other settings (eg, community hospitals, hospitals with smaller networks of outpatient providers, or patients being discharged from surgical services or observation units).