A simple algorithm for predicting bacteremia using food consumption and shaking chills: a prospective observational study

BACKGROUND

Predicting the presence of true bacteremia based on clinical examination is unreliable.

OBJECTIVE

We aimed to construct a simple algorithm for predicting true bacteremia by using food consumption and shaking chills.

DESIGN

A prospective multicenter observational study.

SETTING

Three hospital centers in a large Japanese city.

PARTICIPANTS

In total, 1,943 hospitalized patients aged 14 to 96 years who underwent blood culture acquisitions between April 2013 and August 2014 were enrolled. Patients with anorexia-inducing conditions were excluded.

INTERVENTIONS

We assessed the patients’ oral food intake based on the meal immediately prior to the blood culture with definition as “normal food consumption” when >80% of a meal was consumed and “poor food consumption” when <80% was consumed. We also concurrently evaluated for a history of shaking chills.

MEASUREMENTS

We calculated the statistical characteristics of food consumption and shaking chills for the presence of true bacteremia, and subsequently built

RESULTS

Among 1,943 patients, 223 cases were true bacteremia. Among patients with normal food consumption, without shaking chills, the incidence of true bacteremia was 2.4% (13/552). Among patients with poor food consumption and shaking chills, the incidence of true bacteremia was 47.7% (51/107). The presence of poor food consumption had a sensitivity of 93.7% (95% confidence interval [CI], 89.4%-97.9%) for true bacteremia, and the absence of poor food consumption (ie, normal food consumption) had a negative likelihood ratio (LR) of 0.18 (95% CI, 0.17-0.19) for excluding true bacteremia, respectively. Conversely, the presence of the shaking chills had a specificity of 95.1% (95% CI, 90.7%-99.4%) and a positive LR of 4.78 (95% CI, 4.56-5.00) for true bacteremia.

CONCLUSION

A 2-item screening checklist for food consumption and shaking chills had excellent statistical properties as a brief screening instrument for predicting true bacteremia. Journal of Hospital Medicine 2017;12:510-515. © 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

The underlying clinical diagnoses in the true bacteremic group included urinary tract infection (UTI), pneumonia, abscess, catheter-related bloodstream infection (CRBSI), cellulitis, osteomyelitis, infective endocarditis (IE), chorioamnionitis, iatrogenic infection at hemodialysis puncture sites, bacterial meningitis, septic arthritis, and infection of unknown cause (Supplemental Table 2).

Interrater Reliability Testing of Food Consumption

Patients were evaluated during their hospital stays. The interrater reliability of the evaluation of food consumption was very high across all participating hospitals (Supplemental Table 3). To assess the reliability of the evaluations of food consumption, patients (separate from this main study) were selected randomly and evaluated independently by 2 nurses in 3 different hospitals. The kappa scores of agreement between the nurses at the 3 different hospitals were 0.83 (95% CI, 0.63-0.88), 0.90 (95% CI, 0.80-0.99), and 0.80 (95% CI, 0.67-0.99), respectively. The interrater reliability of food consumption evaluation by the nurses was very high at all participating hospitals.

Food Consumption

The low, moderate, and high food consumption groups consisted of 964 (52.1%), 306 (16.6%), and 577 (31.2%) patients, respectively (Table 1). Of these, 174 (18.0%), 33 (10.8%), and 14 (2.4%) patients, respectively, had true bacteremia. The presence of poor food consumption had a sensitivity of 93.7% (95% CI, 89.4%-97.9%), specificity of 34.6% (95% CI, 33.0%-36.2%), and a positive LR of 1.43 (95% CI, 1.37-1.50) for predicting true bacteremia. Conversely, the absence of poor food consumption (ie, normal food consumption) had a negative LR of 0.18 (95% CI, 0.17-0.19).

Chills

The no, mild, moderate, and shaking chills groups consisted of 1,514 (82.0%), 148 (8.0%), 53 (2.9%), and 132 (7.1%) patients, respectively (Table 1). Of these, 136 (9.0%), 25 (16.9%), 8 (15.1%), and 52 (39.4%) patients, respectively, had true bacteremia. The presence of shaking chills had a sensitivity of 23.5% (95% CI, 22.5%-24.6%), a specificity of 95.1% (95% CI, 90.7%-99.4%), and a positive LR of 4.78 (95% CI, 4.56–5.00) for predicting true bacteremia. Conversely, the absence of shaking chills had a negative LR of 0.80 (95% CI, 0.77-0.84).

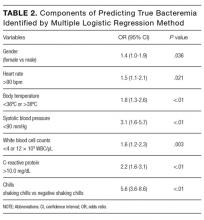

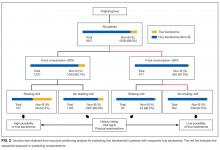

Prediction Model for True Bacteremia

The components identified as significantly related to true bacteremia by multiple logistic regression analysis are indicated in Table 2. The significant predictors of true bacteremia were shaking chills (odds ratio [OR], 5.6; 95% CI, 3.6-8.6; P < .01), SBP <90 mmHg (OR, 3.1; 95% CI, 1.6-5.7; P < 01), CRP levels >10.0 mg/dL (OR, 2.2; 95% CI, 1.6-3.1; P < .01), BT <36°C or >38°C (OR, 1.8; 95% CI, 1.3-2.6; P < .01), WBC <4 × 103/μL or >12 × 103/μL (OR, 1.6; 95% CI, 1.2-2.3; P = .003), HR >90 bpm (OR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.1-2.1; P = .021), and female (OR, 1.4; 95% CI, 1.0-1.9; P = .036). An RPA to create an ideal prediction model for patients with true bacteremia or nonbacteremia is shown in Figure 2. The original group consisted of 1,847 patients, including 221 patients with true bacteremia. The pretest probability of true bacteremia was 2.4% (14/577) for those with normal food consumption (Group 1) and 2.4% (13/552) for those with both normal food consumption and the absence of shaking chills (Group 2). Conversely, the pretest probability of true bacteremia was 16.3% (207/1270) for those with poor food consumption and 47.7% (51/107) for those with both poor food consumption and shaking chills. The patients with true bacteremia with normal food consumption and without shaking chills consisted of 4 cases of CRBSI and UTI, 2 cases of osteomyelitis, 1 case of IE, 1 case of chorioamnionitis, and 1 case for which the focus was unknown (Supplemental Table 4).

DISCUSSION

In this observational study, we evaluated if a simple algorithm using food consumption and shaking chills was useful for assessing whether a patient had true bacteremia. A 2-item screening checklist (nursing assessment of food consumption and shaking chills) had excellent statistical properties as a brief screening instrument for true bacteremia.

We have prospectively validated that food consumption, as assessed by nurses, is a reliable predictor of true bacteremia.8 A previous single-center retrospective study showed similar findings, but these could not be generalized across all institutions because of the limited nature of the study. In this multicenter study, we used 2 statistical methods to reduce selection bias. First, we performed a kappa analysis across the hospitals to evaluate the interrater reliability of the evaluation of food consumption. Second, we used an RPA (Figure 2), also known as a decision tree model. RPA is a step-by-step process by which a decision tree is constructed by either splitting or not splitting each node on the tree into 2 daughter nodes.10 By using this method, we successfully generated an ideal approach to predict true bacteremia using food consumption and shaking chills. After adjusting for food consumption and shaking chills, groups 1 to 2 had sequentially decreasing diagnoses of true bacteremia, varying from 221 patients to only 13 patients.

Appetite is influenced by many factors that are integrated by the brain, most importantly within the hypothalamus. Signals that impinge on the hypothalamic center include neural afferents, hormones, cytokines, and metabolites.11 These factors elicit “sickness behavior,” which includes a decrease in food-motivated behavior.12 Furthermore, exposure to pathogenic bacteria increases serotonin, which has been shown to decrease metabolism in

The strengths of this study include its relatively large sample size, multicenter design, uniformity of data collection across sites, and completeness of data collection from study participants. All of these factors allowed for a robust analysis.

However, there are several limitations of this study. First, the physicians or nurses asked the patients about the presence of shaking chills when they obtained the BCs. It may be difficult for patients, especially elderly patients, to provide this information promptly and accurately. Some patients did not call the nurse when they had shaking chills, and the chills were not witnessed by a healthcare provider. However, we used a more specific definition for shaking chills: a feeling of being extremely cold with rigors and generalized bodily shaking, even under a thick blanket. Second, this algorithm is not applicable to patients with immunosuppressed states because none of the hospitals involved in this study perform bone marrow or organ transplantation. Third, although we included patients with dementia in our cohort, we did not specifically evaluate performance of the algorithm in patients with this medical condition. It is possible that the algorithm would not perform well in this subset of patients owing to their unreliable appetite and food intake. Fourth, some medications may affect appetite, leading to reduced food consumption. Although we have not considered the details of medications in this study, we found that the pretest probability of true bacteremia was low for those patients with normal food consumption regardless of whether the medication affected their appetites or not. However, the question of whether medications truly affect patients’ appetites concurrently with bacteremia would need to be specifically addressed in a future study.