A shocking diagnosis

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

The patient’s symptoms are consistent with anaphylaxis, though prototypical immunoglobulin E (IgE)–mediated anaphylaxis is usually accompanied by urticaria, angioedema, and wheezing, which have been absent during his presentations. There are no clear food, pharmacologic, or environmental precipitants.

Recurrent anaphylaxis can be a manifestation of mast cell excess (eg, cutaneous or systemic mastocytosis). A markedly elevated tryptase level during an anaphylactic episode is consistent with mastocytosis or IgE-mediated anaphylaxis. An elevated baseline tryptase level days after an anaphylactic episode signals increased mast cell burden. There may be a reservoir of mast cells in the bone marrow. Alternatively, the hypervascular pancreatic mass may be a mastocytoma or a mast cell sarcoma (missed because of inadequate sampling or staining).

The lactic acidosis likely reflects global tissue hypoperfusion from vasodilatory hypotension. The leukocytosis may reflect WBC mobilization secondary to endogenous corticosteroids and catecholamines in response to hypotension or may be a direct response to the release of mast cell–derived mediators of inflammation.

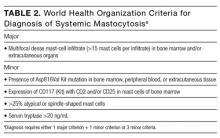

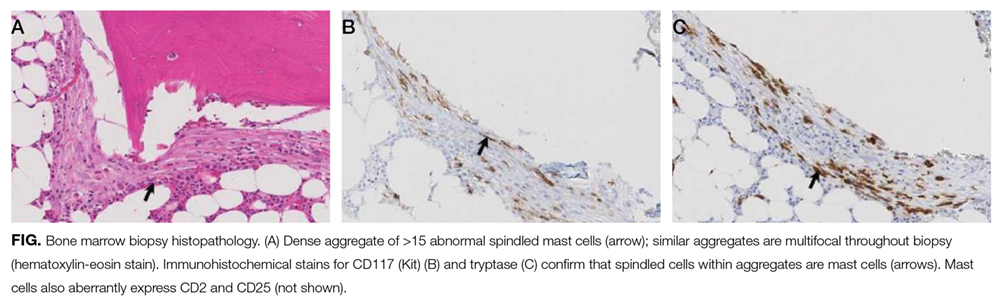

The patient was treated with diphenhydramine and ranitidine. Serum tryptase level was 46.8 ng/mL (normal, <11.5 ng/mL), and 24-hour urine histamine level was 95 µ g/dL (normal, <60 µ g/dL). Bone marrow biopsy results showed multifocal dense infiltrative aggregates of mast cells (>15 cells/aggregate), which were confirmed by CD117 (Kit) and tryptase positivity (Figure). Mutation analysis for Kit Asp816Val, which is present in 80% to 90% of patients with mastocytosis, was positive. He fulfilled the 2008 World Health Organization criteria for systemic mastocytosis (Table 2). Prednisone, histamine inhibitors, and montelukast were prescribed. Six months later, magnetic resonance imaging of the abdomen showed no change in the pancreatic mass, which was now characterized as a possible splenule. The patient had no additional episodes of flushing or syncope over 2 years.

DISCUSSION

Cardiovascular collapse (hypotension, tachycardia, syncope) in an elderly patient prompts clinicians to focus on life-threatening conditions, such as acute coronary syndrome, pulmonary embolus, arrhythmia, and sepsis. Each of these diagnoses was considered early in the course of this patient’s presentations, but each was deemed unlikely as it became apparent that the episodes were self-limited and recurrent over years. Incorporating flushing into the diagnostic problem representation allowed the clinicians to focus on a subset of causes of hypotension.

Flushing disorders may be classified by whether they are mediated by the autonomic nervous system (wet flushes, because they are usually accompanied by diaphoresis) or by exogenous or endogenous vasoactive substances (dry flushes).1 Autonomic nervous system flushing is triggered by emotions, fever, exercise, perimenopause (hot flashes), and neurologic conditions (eg, Parkinson disease, spinal cord injury, multiple sclerosis). Vasoactive flushing precipitants include drugs (eg, niacin); alcohol (secondary to cutaneous vasodilation, or acetaldehyde particularly in people with insufficient acetaldehyde dehydrogenase activity)2; foods that contain capsaicin, tyramine, sulfites, or histamine (eg, eating improperly handled fish can cause scombroid poisoning); and anaphylaxis. Rare causes of vasoactive flushing include carcinoid syndrome, pheochromocytoma, medullary thyroid carcinoma, VIPoma, and mastocytosis.2

Mastocytosis is a rare clonal disorder characterized by the accumulation of abnormal mast cells in the skin (cutaneous mastocytosis), in multiple organs (systemic mastocytosis), or in a solid tumor (mastocytoma). Urticaria pigmentosa is the most common form of cutaneous mastocytosis; it is seen more often in children than in adults and typically is associated with a maculopapular rash and dermatographism. Systemic mastocytosis is the most common form of the disorder in adults.3 Symptoms are related to mast cell infiltration or mast cell mediator–related effects, which range from itching, flushing, and diarrhea to hypotension and anaphylaxis. Other manifestations are fatigue, urticaria pigmentosa, osteoporosis, hepatosplenomegaly, bone pain, cytopenias, and lymphadenopathy.4

Systemic mastocytosis can occur at any age and should be considered in patients with recurrent unexplained flushing, syncope, or hypotension. Eighty percent to 90% of patients with systemic mastocytosis have a mutation in Kit,5 a transmembrane tyrosine kinase that is the receptor for stem cell factor. The Asp816Val mutation leads to increased proliferation and reduced apoptosis of mast cells.3,6,7 Proposed diagnostic algorithms8-11 involve measurement of serum tryptase levels and examination of bone marrow. Bone marrow biopsy and testing for the Asp816Val

The primary goals of treatment are managing mast cell–mediated symptoms and, in advanced cases, achieving cytoreduction. Alcohol can trigger mast cell degranulation in indolent systemic mastocytosis and should be avoided. Mast cell–mediated symptoms are managed with histamine blockers, leukotriene antagonists, and mast cell stabilizers.12 Targeted therapy with tyrosine kinase inhibitors (eg, imatinib) in patients with transmembrane Kit mutation (eg, Phe522Cys, Lys509Ile) associated with systemic mastocytosis has had promising results.13,14 However, this patient’s Asp816Val mutation is in the Kit catalytic domain, not the transmembrane region, and therefore would not be expected to respond to imatinib. A recent open-label trial of the multikinase inhibitor midostaurin demonstrated resolution of organ damage, reduced bone marrow burden, and lowered serum tryptase levels in patients with advanced systemic mastocytosis.15 Interferon, cladribine, and high-dose corticosteroids are prescribed in patients for whom other therapies have been ineffective.8

The differential diagnosis is broad for both hypotension and for flushing, but the differential diagnosis for recurrent hypotension and flushing is limited. Recognizing that flushing was an essential feature of this patient’s hypotensive condition, and not an epiphenomenon of syncope, allowed the clinicians to focus on the overlap and make a shocking diagnosis.