A shocking diagnosis

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

The recurring yet self-limited nature, diaphoresis, flushing, and facial erythema suggest a non-sepsis distributive cause of hypotension. It is possible the patient is recurrently exposed to a toxin (eg, alcohol) that causes both flushing and dehydration. Flushing disorders include carcinoid syndrome, pheochromocytoma, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS), and mastocytosis. Carcinoid syndrome is characterized by bronchospasm and diarrhea and, in some cases, right-sided valvulopathy, all of which are absent in this patient. Pheochromocytoma is associated with orthostasis, but patients typically are hypertensive at baseline. DRESS, which may arise from nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) or aspirin use, can cause facial erythema and swelling but is also characterized by liver, renal, and hematologic abnormalities, none of which was demonstrated. Furthermore, DRESS typically does not cause hypotension. Mastocytosis can manifest as isolated or recurrent anaphylaxis.

It is important to investigate antecedents of these syncopal episodes. If the earlier episodes were food-related—one occurred at a restaurant—then deglutition syncope (syncope precipitated by swallowing) should be considered. If an NSAID or aspirin was ingested before each episode, then medication hypersensitivity or mast cell degranulation (which can be triggered by these medications) should be further examined. Loss of consciousness lasting 20 minutes without causing any neurologic sequelae is unusual for most causes of recurrent syncope. This feature raises the possibility that a toxin or mediator might still be present in the patient’s system.

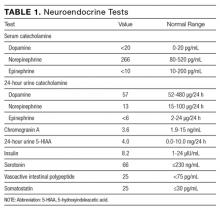

Serial cardiac enzymes and electrocardiogram were normal. A tilt-table study was negative. The cortisol response to ACTH (cosyntropin) stimulation was normal. The level of serum tryptase, drawn 2 days after syncope, was 18.4 ng/dL (normal, <11.5 ng/dL). Computed tomography scan of chest and abdomen was negative for pulmonary embolism but showed a 1.4×1.3-cm hypervascular lesion in the tail of pancreas. The following neuroendocrine tests were within normal limits: serum and urine catecholamines; urine 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA); and serum chromogranin A, insulin, serotonin, vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP), and somatostatin (Table 1). The patient remained asymptomatic during his hospital stay and was discharged home with appointments for cardiology follow-up and endoscopic ultrasound-guided biopsy of the pancreatic mass.

Pheochromocytoma is unlikely with normal serum and urine catecholamine levels and normal adrenal images. The differential diagnosis for a pancreatic mass includes pancreatic carcinoma, lymphoma, cystic neoplasm, and neuroendocrine tumor. All markers of neuroendocrine excess are normal, though elevations can be episodic. The normal 5-HIAA level makes carcinoid syndrome unlikely. VIPomas are associated with flushing, but the absence of profound and protracted diarrhea makes a VIPoma unlikely.

As hypoglycemia from a pancreatic insulinoma is plausible as a cause of episodic loss of consciousness lasting 15 minutes or more, it is important to inquire if giving food or drink helped resolve previous episodes. The normal insulin level reported here is of limited value, because it is the combination of insulin and C-peptide levels at time of hypoglycemia that is diagnostic. The normal glucose level recorded during one of the earlier episodes and the hypotension argue against hypoglycemia.

The elevated tryptase level is an indicator of mast cell degranulation. Tryptase levels are transiently elevated during the initial 2 to 4 hours after an anaphylactic episode and then normalize. An elevated level many hours or days later is considered a sign of mast cell excess. Although there is no evidence of the multi-organ disease (eg, cytopenia, bone disease, hepatosplenomegaly) seen in patients with a high systemic burden of mast cells, mast cell disorders exist on a spectrum. There may be a focal excess of mast cells confined to one organ or an isolated mass.

The same day as discharge, the patient’s wife drove them to the grocery store. He remained in the car while she shopped. When she returned, she found him confused and minimally responsive with subsequent brief loss of consciousness. He was taken to an ED, where he was flushed and hypotensive (systolic BP, 60 mm Hg) and tachycardic. Other examination findings were normal. After fluid resuscitation he became alert and oriented. WBC count was 20,850/μL with 89% neutrophils, hemoglobin level was 14.6 g/dL, and platelet count was 168,000/μL. Serum lactate level was 3.7 mmol/L (normal, <2.3 mmol/L). Chest radiograph was normal. He was treated with broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy and admitted to the hospital. Blood and urine cultures were sterile. Fine-needle aspiration of the pancreatic mass demonstrated nonspecific inflammation. Four days after admission (3 days after pancreatic mass biopsy) the patient developed palpitations, felt unwell, and had marked flushing of the face and trunk, with concomitant BP of 90/50 mm Hg and HR of 140 bpm.

The salient features of this case are recurrent hypotension, tachycardia, and flushing. Autonomic insufficiency, to which elderly patients are prone, causes hemodynamic perturbations but rarely flushing. The patient does not have diabetes mellitus, Parkinson disease, or another condition that puts him at risk for dysautonomia. Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors secrete mediators that lead to vasodilation and hypotension but are unlikely given the clinical and biochemical data.