Addressing the rarity and complexities of sarcomas

Citation JCSO 2018;16(4):e210-e215

©2018 Frontline Medical Communications

doi https://doi.org/10.12788/jcso.0418

Related content

Patterns of malignancies in patients with HIV-AIDS

Submit a paper here

Long-sought success for STS

Sunitinib and regorafenib include PDGFRα and the vascular endothelial growth factor receptors (VEGFRs) among their targets, receptors that play crucial roles in the formation of new blood vessels (angiogenesis). Many types of non-GIST sarcomas have been shown to be highly vascularized and express high levels of both of those receptors and other angiogenic proteins, which sparked interest in the development of multitargeted TKIs and other anti-angiogenic drugs in patients with STS.18

In 2012, pazopanib became the first FDA-approved molecularly targeted therapy for the treatment of non-GIST sarcomas. Approval in the second-line setting was based on the demonstration of a 3-month improvement in PFS compared with placebo.19 Four years later, the monoclonal antibody olaratumab, a more specific inhibitor of PDGFRα, was approved in combination with doxorubicin, marking the first front-line approval for more than 4 decades.20Numerous other anti-angiogenic drugs continue to be evaluated for the treatment of advanced STS. Among them, anlotinib is being tested in phase 3 clinical trials, and results from the ALTER0203 trial were presented at the 2018 annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).21 After failure of chemotherapy, 223 patients were randomly assigned to receive either anlotinib or placebo. Anlotinib significantly improved median PFS across all patients, compared with placebo (6.27 vs 1.4 months, respectively; hazard ratio [HR], 0.33; P < .0001), but was especially effective in patients with alveolar soft part sarcoma (ASPS; mPFS: 18.2 vs 3 months) and was well tolerated.21

,Sarcoma secrets revealed

Advancements in genome sequencing technologies have made it possible to interrogate the molecular underpinnings of sarcomas in greater detail. However, their rarity presents a significant technical challenge, with a dearth of samples available for genomic testing. Large-scale worldwide collaborative efforts have facilitated the collection of sufficiently large patient populations to provide statistically robust data in many cases. The Cancer Genome Atlas has established a rare tumor characterization project to facilitate the genomic sequencing of rare cancer types like sarcomas.

Genome sequencing studies have revealed 2 types of sarcomas: those with relatively stable genomes and few molecular alterations, exemplified by Ewing sarcoma, which has a mutational load of 0.15 mutations/Megabase (Mb); and those that are much more complex with frequent somatic mutations, the prime example being leiomyosarcoma. The latter are characterized by mutations in the TP53 gene, dubbed the “guardian of the genome” for its essential role in genome stability.

The 2 types are likely to require very different therapeutic strategies. Although genomically complex tumors offer up lots of potential targets for therapy, they also display significant heterogeneity and it can be challenging to find a shared target across different tumor samples. The p53 protein would make a logical target but, to date, tumor suppressor proteins are not readily druggable.

The most common type of molecular alterations in sarcomas are chromosomal translocations, where part of a chromosome breaks off and becomes reattached to another chromosome. This can result in the formation of a gene fusion when parts of 2 different genes are brought together in a way in which the genetic code can still be read, leading to the formation of a fusion protein with altered activity.22-25

In sarcomas, these chromosomal translocations predominantly involve genes encoding transcription factors and the gene fusion results in their aberrant expression and activation of the transcriptional programs that they regulate.

Ewing sarcoma is a prime example of a sarcoma that is defined by chromosomal translocations. Most often, the resulting gene fusions occur between members of theten-eleven translocation (TET) family of RNA-binding proteins and the E26 transformation-specific (ETS) family of transcription factors. The most common fusion is between the EWSR1 and FLI1 genes, observed in between 85% and 90% of cases.

Significant efforts have been made to target EWSR1-FLI1. Since direct targeting of transcription factors is challenging, those efforts focused on targeting the aberrant transcriptional programs that they initiate. A major downstream target is the insulin-like growth factor receptor 1 (IGF1R) and numerous IGF1R inhibitors were developed and tested in patients with Ewing sarcoma, but unfortunately success was limited. Attention turned to the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) as a potential mechanism of resistance to IGF1R inhibitors and explanation for the limited responses. Clinical trials combining mTOR and IGF1R inhibitors also proved unsuccessful.26

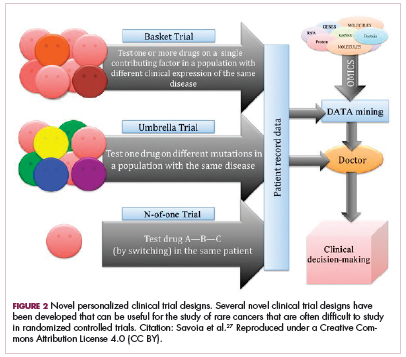

Although overall these trials were deemed failures, they were notable for the dramatic responses that were seen in 1 or 2 patients. Researchers are probing these “exceptional responses” using novel N-of-1 clinical trial designs that focus on a single patient (Figure 2).27-30 More recently, the first drug to specifically target the EWSR1-FLI1 fusion protein was developed. TK216 binds to the fusion protein and prevents it from binding to RNA helicase A, thereby blocking its function.31

Another type of gene fusion, involving the neurotrophic tropomyosin receptor kinase (NTRK) genes, has recently come into the spotlight for the treatment of lung cancer. According to a recent study, NTRK fusions may also be common in sarcomas. They were observed in 8% of patients with breast sarcomas, 5% with fibrosarcomas, and 5% with stomach or small intestine sarcomas.32

The NTRK genes encode TRK proteins and several small molecule inhibitors of TRK have been developed to treat patients with NTRK fusion-positive cancers. Another novel clinical trial design – the basket trial – is being used to test these inhibitors. This type of trial uses a tumor-agnostic approach, recruiting patients with all different histological subtypes of cancer that are unified by the shared presence of a specific molecular alteration.33