Extramedullary plasmacytoma of the thyroid, refractory to radiation therapy and treated with bortezomib

Accepted for publication July 17, 2018

Correspondence

Subash Ghimire, MD; drsubash01@gmail.com

Disclosures The authors report no disclosures/conflicts of interest.

Citation JCSO 2018;16(5):e206-e209

©2018 Frontline Medical Communications

doi https://doi.org/10.12788/jcso.0414

Submit a paper here

Plasma cell neoplasms involving tissues other than the bone marrow are known as extramedullary plasmacytoma (EMP).1 EMPs mostly involve the head and neck region.2 Solitary EMP involving only the thyroid gland is very rare.3,4 Because of the limited knowledge about this condition and its rarity, its management can be challenging and is often extrapolated from plasma cell myeloma.5,6 In general, surgery or radiation are considered as front-line therapy.3,5 EMPs usually respond well to radiotherapy with almost complete remission. No definite guidelines outlining the treatment of radio-resistant EMP of the thyroid have yet been published. Data supporting the use of chemotherapy is particularly limited.4,7,8

Here, we describe the case of a 53-year-old woman with a long history of thyroiditis who presented with rapidly worsening symptomatic thyroid enlargement. She was diagnosed with EMP of the thyroid gland that was not amenable to surgery and was refractory to radiotherapy but responded to adjuvant chemotherapy with bortezomib. This report highlights 2 unique aspects of this condition: it focuses on a rare case of EMP and, as far as we know, it reports for the first time on EMP that was resistant to radiotherapy. It also highlights the need for guidelines for the treatment of EMPs.

Case presentation and summary

A 53-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with complaints of difficulty swallowing, hoarseness, and neck pain during the previous 1 month. She had a known history of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, and an ultrasound scan of her neck 6 years previously had demonstrated diffuse thyromegaly without discrete nodules. On presentation, the patient’s vitals were stable, and a neck examination revealed a firm and enlarged thyroid without any cervical adenopathy. Laboratory investigations revealed a normal complete blood count and comprehensive metabolic panel. She had an elevated thyroid-stimulating hormone level of 13.40 mIU/L (reference range, 0.47-4.68 mIU/L) and normal thyroxine level of 4.5 pmol/L (reference range, 4.5-12.0 pmol/L). A computerized tomography (CT) scan of the neck revealed an enlarged thyroid gland (right lobe length, 10.3 cm; isthmus, 2 cm; left lobe, 8 cm) with a focal area of increased echogenicity in the midpole of the left lobe measuring 9.5 mm × 5.5 mm. The patient was discharged to home with pain medications, and urgent follow-up with an otolaryngologist was arranged. A flexible laryngoscopy was done in the otolaryngology clinic, which revealed retropharyngeal bulging that correlated with the thyromegaly evident on the CT scan.

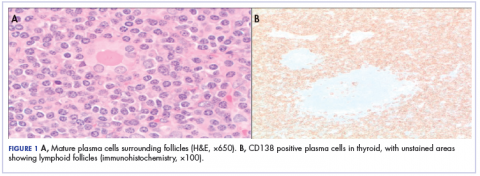

,Because of the patient’s significant symptoms, we decided to proceed with surgery with a clinical diagnosis of likely thyroiditis. A left subtotal thyroidectomy with extension to the superior mediastinum was performed, but a right thyroidectomy could not be done safely. On gross examination, a well-capsulated left lobe with a tan-white, lobulated, soft cut surface was seen. Microscopic examination revealed replacement of thyroid parenchyma with sheets of mature-appearing plasma cells with eccentric round nuclei, abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm without atypia, and few scattered thyroid follicles with lymphoepithelial lesions (Figure 1A). Immunohistochemistry confirmed plasma cells with expression of CD138 (Figure 1B).

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) showed that the neoplastic plasma cells contained monotypic kappa immunoglobulin light chain messenger RNA. Clonal immunoglobulin gene rearrangement was detected on polymerase chain reaction. A diagnosis of plasmacytoma of the thyroid gland in a background of thyroiditis was made on the basis of the aforementioned observations.

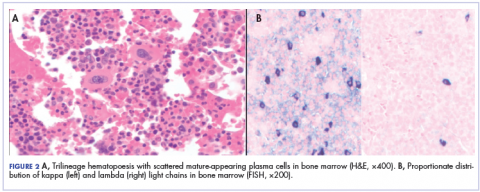

After that diagnosis, we performed an extensive work-up for plasma cell myeloma. Bone marrow biopsy showed normal maturing trilineage hematopoiesis with scattered mature-appearing plasma cells Figure 2A. Flow cytometry showed a rare (0.2%) population of polytypic plasma cells and was confirmed by CD138 immunohistochemistry. FISH showed proportionate distribution (2-5:1) of kappa and lambda light chains in plasma cells (Figure 2B).

Serum protein electrophoresis showed normal levels of serum proteins with no M spike. Serum total protein was 7.9 g/dL, albumin 5.0 g/dL, α1-globulin 0.3 g/dL, α2-globulin 0.8 g/dL, β-globulin 0.7 g/dL, and γ-globulin 1.6 g/dL, with an albumin–globulin ratio of 1.47. Calcium and β2-microglobulin were also in the normal ranges. Serum-free kappa light chain was found to be elevated (20.9 mg/L; reference range, 3.3-19.4 mg/L). The immunoglobulin G level was also elevated at 3,104 mg/dL (reference range, 700-1,600 mg/dL).

A positron-emission tomographic (PET) scan done 1 month after the surgery showed no other sites of disease except the thyroid. No lytic bone lesions were present. The patient was treated with 50.4 Gy of radiation by external beam radiotherapy to the thyroid in 28 fractions as definitive therapy. Despite treatment with surgery and radiation, she continued to have pain around the neck, and a repeat PET scan 3 months after completion of radiation showed persistent uptake in the thyroid. Because of her refractoriness to radiotherapy, she was started on systemic therapy with a weekly regimen of bortezomib and dexamethasone for 9 cycles. Her symptoms began to resolve, and a repeat PET scan done after completion of chemotherapy showed no evidence of uptake, suggesting adequate response to chemotherapy, and chemotherapy was therefore stopped. The patient was scheduled a regular follow-up in 3 months. Because of continued local symptoms in this follow-up period, the decision was made to perform surgical gland removal, and she underwent completion of