Immunotherapy may hold the key to defeating virally associated cancers

Citation JCSO 2018;16(2):e110-e116

©2018 Frontline Medical Communications

doi https://doi.org/10.12788/jcso.0399

Submit a paper here

Hepatocellular carcinoma: a tale of two viruses

The hepatitis viruses are a group of 5 unrelated viruses that causes inflammation of the liver. Hepatitis B (HBV), a DNA virus, and hepatitis C (HCV), an RNA virus, are also oncoviruses; HBV in particular is one of the main causes of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the most common type of liver cancer.

The highly inflammatory environment fostered by HBV and HCV infection causes liver damage that often leads to cirrhosis. Continued infection can drive permanent damage to the hepatocytes, leading to genetic and epigenetic damage and driving oncogenesis. As an RNA virus, HCV doesn’t integrate into the genome and no confirmed viral oncoproteins have been identified to date, therefore it mostly drives cancer through these indirect mechanisms, which is also reflected in the fact that HCV-associated HCC predominantly occurs against a backdrop of liver cirrhosis.

HBV does integrate into the host genome. Genome sequencing studies revealed hundreds of integration sites, but most commonly they disrupted host genes involved in telomere stability and cell cycle regulation, providing some insight into the mechanisms by which HBV-associated HCC develops. In addition, HBV produces several oncoproteins, including HBx, which disrupts gene transcription, cell signaling pathways, cell cycle progress, apoptosis and other cellular processes.15,16

,Multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) have been the focal point of therapeutic development in HCC. However, following the approval of sorafenib in 2008, there was a dearth of effective new treatment options despite substantial efforts and numerous phase 3 trials. More recently, immunotherapy has also come to the forefront, especially immune checkpoint inhibitors.

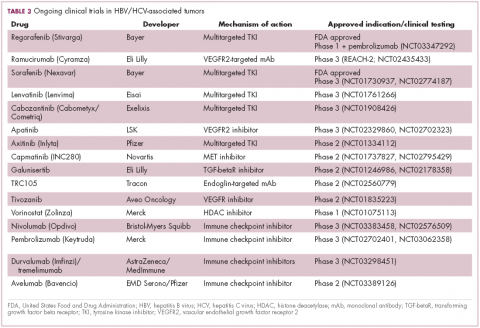

Last year marked the first new drug approvals in nearly a decade – the TKI regorafenib (Stivarga) and immune checkpoint inhibitor nivolumab (Opdivo), both in the second-line setting after failure of sorafenib. Treatment options in this setting may continue to expand, with the TKIs cabozantinib and lenvatinib and the immune checkpoint inhibitor pembrolizumab and the combination of durvalumab and tremelimumab hot on their heels.17-20 Many of these drugs are also being evaluated in the front-line setting in comparison with sorafenib (Table 3).

At the current time, the treatment strategy for patients with HCC is independent of etiology, however, there are significant ongoing efforts to try to tease out the implications of infection for treatment efficacy. A recent meta-analysis of patients treated with sorafenib in 3 randomized phase 3 trials (n = 3,526) suggested that it improved overall survival (OS) among patients who were HCV-positive, but HBV-negative.21

Studies of the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2-targeting monoclonal antibody ramucirumab, on the other hand, suggested that it may have a greater OS benefit in patients with HBV, while regorafenib seemed to have a comparable OS benefit in both subgroups.22-25 The immune checkpoint inhibitors studied thus far seem to elicit responses irrespective of infection status.

A phase 2 trial of the immune checkpoint inhibitor tremelimumab was conducted specifically in patients with advanced HCC and chronic HCV infection. The disease control rate (DCR) was 76.4%, with 17.6% partial response (PR) rate. There was also a significant drop in viral load, suggesting that tremelimumab may have antiviral effects.26,27,28

Adoptive cell therapy promising in EBV-positive cancers

More than 90% of the global population is infected with EBV, making it one of the most common human viruses. It is a member of the herpesvirus family that is probably best known as the cause of infectious mononucleosis. On rare occasions, however, EBV can cause tumor development, though our understanding of its exact pathogenic role in cancer is still incomplete.

EBV is a DNA virus that doesn’t tend to integrate into the host genome, but instead remains in the nucleus in the form of episomes and produces several oncoproteins, including latent membrane protein-1. It is associated with a range of different cancer types, including Burkitt lymphoma and other B-cell malignancies. It also infects epithelial cells and can cause nasopharyngeal carcinoma and gastric cancer, however, much less is known about the molecular underpinnings of these EBV-positive cancer types.26,27Gastric cancers actually comprise the largest group of EBV-associated tumors because of the global incidence of this cancer type. The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network recently characterized gastric cancer on a molecular level and identified an EBV-positive subgroup as a distinct clinical entity with unique molecular characteristics.29

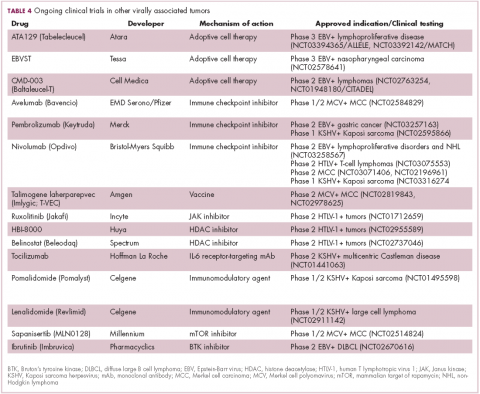

The focus of therapeutic development has again been on immunotherapy, however in this case the idea of collecting the patients T cells, engineering them to recognize EBV, and then reinfusing them into the patient – adoptive cell therapy – has gained the most traction (Table 4).

Two presentations at the American Society of Hematology annual meeting in 2017 detailed ongoing clinical trials of Atara Biotherapeutics’ ATA129 and Cell Medica’s CMD-003. ATA129 was associated with a high response rate and a low rate of serious AEs in patients with posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder; ORR was 80% in 6 patients treated after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, and 83% in 6 patients after solid organ transplant.30

CMD-003, meanwhile, demonstrated preliminary signs of activity and safety in patients with relapsed extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, according to early results from the phase 2 CITADEL trial. Among 6 evaluable patients, the ORR was 50% and the DCR was 67%.31