Immunotherapy may hold the key to defeating virally associated cancers

Citation JCSO 2018;16(2):e110-e116

©2018 Frontline Medical Communications

doi https://doi.org/10.12788/jcso.0399

Submit a paper here

Infection with certain viruses has been causally linked to the development of cancer. In recent years, an improved understanding of the unique pathology and molecular underpinnings of these virally associated cancers has prompted the development of more personalized treatment strategies, with a particular focus on immunotherapy. Here, we describe some of the latest developments.

The link between viruses and cancer

Suspicions about a possible role of viral infections in the development of cancer were first aroused in the early 1900s. The seminal discovery is traced back to Peyton Rous, who showed that a malignant tumor growing in a chicken could be transferred to a healthy bird by injecting it with tumor extracts that contained no actual tumor cells.1

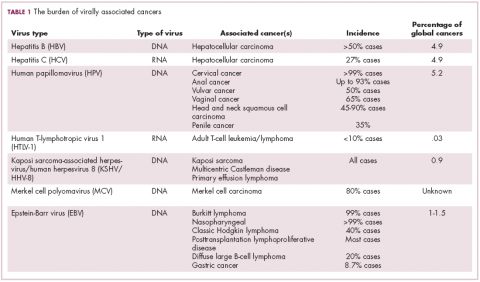

The infectious etiology of human cancer, however, remained controversial until many years later when the first cancer-causing virus, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), was identified in cell cultures from patients with Burkitt lymphoma. Shortly afterward, the Rous sarcoma virus was unveiled as the oncogenic agent behind Rous’ observations.2Seven viruses have now been linked to the development of cancers and are thought to be responsible for around 12% of all cancer cases worldwide. The burden is likely to increase as technological advancements make it easier to establish a causal link between viruses and cancer development.3

,In addition to making these links, researchers have also made significant headway in understanding how viruses cause cancer. Cancerous transformation of host cells occurs in only a minority of those who are infected with oncogenic viruses and often occurs in the setting of chronic infection.

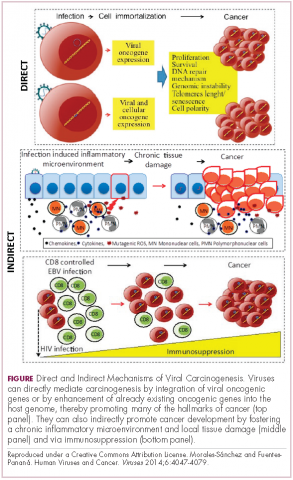

Viruses can mediate carcinogenesis by direct and/or indirect mechanisms (Figure 1). Many of the hallmarks of cancer, the key attributes that drive the transformation from a normal cell to a malignant one, are compatible with the virus’s needs, such as needing to avoid cell death, increasing cell proliferation, and avoiding detection by the immune system.

Viruses hijack the cellular machinery to meet those needs and they can do this either by producing viral proteins that have an oncogenic effect or by integrating their genetic material into the host cell genome. When the latter occurs, the process of integration can also cause damage to the DNA, which further increases the risk of cancer-promoting changes occurring in the host genome.

Viruses can indirectly contribute to carcinogenesis by fostering a microenvironment of chronic inflammation, causing oxidative stress and local tissue damage, and by suppressing the antitumor immune response.4,5

Screening and prevention efforts have helped to reduce the burden of several different virally associated cancers. However, for the substantial proportion of patients who are still affected by these cancers, there is a pressing need for new therapeutic options, particularly since genome sequencing studies have revealed that these cancers can often have distinct underlying molecular mechanisms.

Vaccines lead the charge in HPV-driven cancers

German virologist Harald zur Hausen received the Nobel Prize in 2008 for his discovery of the oncogenic role of human papillomaviruses (HPVs), a large family of more than 100 DNA viruses that infect the epithelial cells of the skin and mucous membranes. They are responsible for the largest number of virally associated cancer cases globally – around 5% (Table 1).

A number of different cancer types are linked to HPV infection, but it is best known as the cause of cervical cancer. The development of diagnostic blood tests and prophylactic vaccines for prevention and early intervention in HPV infection has helped to reduce the incidence of cervical cancer. Conversely, another type of HPV-associated cancer, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC), has seen increased incidence in recent years.

HPVs are categorized according to their oncogenic potential as high, intermediate, or low risk. The high-risk HPV16 and HPV18 strains are most commonly associated with cancer. They are thought to cause cancer predominantly through integration into the host genome. The HPV genome is composed of 8 genes encoding proteins that regulate viral replication and assembly. The E6 and E7 genes are the most highly oncogenic; as the HPV DNA is inserted into the host genome, the transcriptional regulator of E6/E7 is lost, leading to their increased expression. These genes have significant oncogenic potential because of their interaction with 2 tumor suppressor proteins, p53 and pRb.6,7

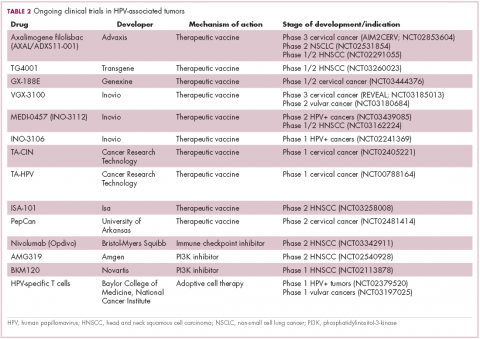

The largest investment in therapeutic development for HPV-positive cancers has been in the realm of immunotherapy in an effort to boost the anti-tumor immune response. In particular, there has been a focus on the development of therapeutic vaccines, designed to prime the anti-tumor immune response to recognize viral antigens. A variety of different types of vaccines are being developed, including live, attenuated and inactivated vaccines that are protein, DNA, or peptide based. Most developed to date target the E6/E7 proteins from the HPV16/18 strains (Table 2).8,9

Other immunotherapies are also being evaluated, including immune checkpoint inhibitors, antibodies designed to target one of the principal mechanisms of immune evasion exploited by cancer cells. The combination of immune checkpoint inhibitors with vaccines is a particularly promising strategy in HPV-associated cancers. At the European Society for Medical Oncology Congress in 2017, the results of a phase 2 trial of nivolumab in combination with ISA-101 were presented.

Among 24 patients with HPV-positive tumors, the majority oropharyngeal cancers, the combination elicited an overall response rate (ORR) of 33%, including 2 complete responses (CRs). Most adverse events (AEs) were mild to moderate in severity and included fever, injection site reactions, fatigue and nausea.14