Qualitative assessment of organizational barriers to optimal lung cancer care in a community hospital setting in the United States

Background Lung cancer is a major public health challenge in the United States with a complicated process of care delivery. In addition, it is a challenge for many lung cancer patients and their caregivers to navigate health care systems while coping with the disease.

Objective To explore the organizational barriers to receiving quality health care from the perspective of lung cancer patients and their caregivers.

Methods In a qualitative study involving 10 focus groups of patients and their caregivers, we recorded and transcribed guided discussions for analysis by using Dedoose software to investigate recurrent themes.

Results Analysis of the transcriptions revealed 4 recurring themes related to organizational barriers to quality care: insurance, scheduling, communication, and knowledge. The participants perceived support with navigating the health care system, either through their own social network or from within the health care systems, as beneficial in coping with the lung cancer, seeking information, expediting appointments, connecting patients to physicians, and receiving timely care.

Limitations Institutional and geographic differences in the experience of lung cancer care may limit the generalizability of the results of this study.

Conclusions This study offers insights into the perspectives of lung cancer patients and caregivers on the organizational barriers to receiving quality care. Targeting barriers related to insurance coverage, appointment scheduling, provider-patient communication, and patient or family education about lung cancer and its treatment process will likely improve patient and caregiver experience of care.

Funding Partially funded through a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute Award (IH-1304-6147).

Accepted for publication March 2, 2018

Correspondence Raymond U Osarogiagbon, MBBS; rosarogi@bmhcc.org

Disclosures The authors report no disclosures/conflicts of interest.

Citation JCSO 2018;16(2):e89-e96.

©2018 Frontline Medical Communications

doi https://doi.org/10.12788/jcso.0394

Submit a paper here

Lung cancer is a major public health challenge in the United States. It is the leading cause of cancer death in the United States, accounting for 27% of all cancer deaths, and it has an aggregate 5-year survival rate of 18%.1 Advances in diagnostic and treatment options are rapidly increasing the complexity of lung cancer care delivery, which involves multiple specialty providers and often cuts across health care institutions.2-4 Navigating the process of care while coping with the complexities of the illness can be overwhelming for both the patient and the caregiver.5 With increasing regulations and cost-cutting measures, the health care system in the United States can pose many challenges, especially for those dealing with catastrophic and life-threatening illnesses. Any barrier to accessing care often increases anxiety in patients, who are already trying to cope with the management of their disease.6-8

The concept of barriers to quality care (such as the receipt of timely and appropriate diagnostic and staging work-up and treatment selection according to evidence-based guidelines) is generally used in the context of improving health care management or prevention programs.9-13 Barriers might include high costs, transportation, distance, underinsurance, limited hours for access to care, patient sharing by physicians, and a lack of access to information about physicians’ recommendations.10,14-16 Such barriers have been categorized as organizational (leadership and workforce), structural (process of care), clinical (provider-patient encounter), and macro (policy and population).17,18 Organizational barriers are defined as impediments encountered within the medical system and health care organizations when accessing, receiving, and delivering care.12 Several organizational barriers have been identified in the literature based on characteristics of the targeted population (eg, race, ethnicity, type of illness), key stakeholder views, and aspects of care (eg, screening, preventive practice, care, and treatment).

In a systematic review, Betancourt and colleagues reported provider-patient interactions, processes of care, and language as some of the barriers to receiving quality care.17 Although cancer screening has been shown to reduce mortality in the adult population for several types of cancer,19-21 barriers that impede access to services have been identified as emanating not only from the macro level (eg, age of screening, reimbursement problems, screening guidelines) or inter- and intra-individual levels (eg, awareness of screening, various perspectives on life and cancer, comorbidities, social support), but also from the organization (organizational infrastructure that inhibits screening because of limited participation in research trials) and provider levels (impaired communication regarding screening between patient and physician, low commitment to shared decision-making, provider’s awareness of screening and screening guidelines).18 Other organizational barriers, such as difficulty navigating the health care system, poor interaction between patients and medical staff, and language barriers, have been identified in a systematic review of breast cancer screening in immigrant and minority women.22

,Other barriers to quality cancer care reported by patients include knowledge about the disease and treatment, poor communication with providers, lack of coordination and timeliness of care, and lack of attention to care. Providers have identified other barriers to quality care, which include a lack of access to care, reimbursement problems, poor psychosocial support services, accountability of care, provider workload, and inadequate patient education.23 Few qualitative studies have been conducted to understand the organizational barriers that lung cancer patients and their caregivers face within the health care system.

Through the use of focus groups, we sought the perspectives of lung cancer patients and their caregivers on the organizational barriers that they experience while navigating the health care system. Identifying and understanding these barriers can help health care professionals work with patients and their caregivers to alleviate these stressors in an already difficult time.3,24 In addition, a more thorough understanding of patients’ and caregivers’ perspectives on organizational barriers may help improve health care delivery and, thus, patient satisfaction.

Methods

With the approval of the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Memphis and the Baptist Memorial Health Care Corporation, we conducted focus groups with lung cancer patients and their informal caregivers to understand the challenges they encounter while navigating the health care system during their illness. The Baptist Memorial Health Care system is centered in the Mid-South region of the United States, which has some of the highest US lung cancer incidence rates.25

Research staff identified potential participants from a roster of patients provided by treatment clinics within the system. Patients eligible for this study had received care for suspected lung cancer within a community-based health care system within 6 months preceding the date of the focus group. Eligible patients were approached by the research staff by cold calling or in-person contact during clinic visits for their consent to participate in the study. From a compiled list of 219 patients, 89 received initial contact to gauge interest. Of those, 42 patients were formally approached and asked to participate; 22 agreed to participate, and 20 did not participate for reasons including illness, previous participation in other forms of patient feedback, lack of interest, failure to show up to focus group sessions, change of mind, lack of transportation, or other commitments. Patients identified their informal caregivers to form patient-caregiver dyads. All patients and caregivers provided written informed consent before participating in the focus groups.

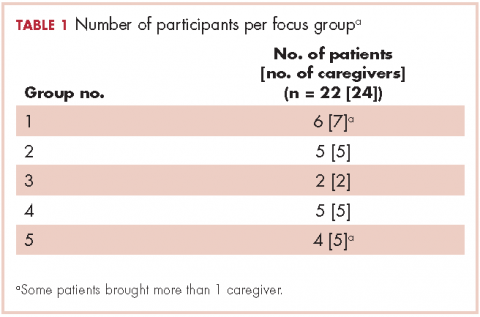

We conducted 10 focus groups during March 2013 through January 2014 – 5 with 22 patients and 5 with 24 caregivers (Table 1). Eight of the focus groups were conducted in Memphis, Tennessee, and to obtain the perspectives of patients from a rural setting, we conducted 2 focus groups in Grenada, Mississippi. All of the focus groups were facilitated by a medical anthropologist (SK) and a clinical psychologist (KDW), neither of whom was affiliated with the health care system. Each facilitator was accompanied by a note-taker. Patient-caregiver dyads came to the designated location together. Two focus groups (one for patients, the other for caregivers) were then conducted simultaneously in 2 separate rooms. The facilitators used a pilot-tested focus group interview guide during each session. The items in the focus group guide revolved around experience with the health care system in diagnosis and treatment; timeliness with appointments and procedures for diagnosis and subsequent care; physician communication in being informed about the disease, treatment, and getting questions answered; coordination of care; other challenges in receiving quality care; and suggestions for improving the patient and caregiver experience with the health care system.

The focus group sessions lasted 1 to 2 hours and were audiorecorded and transcribed verbatim. The data were analyzed by using Dedoose software version 5.0.11 (Sociocultural Research Consultants, Los Angeles, California). Data collection and analysis were conducted concurrently to achieve theoretical saturation. Creswell’s 7-step analysis framework was used as a guide to code and interpret the data.26 The process involved collecting raw data, preparing and organizing transcripts, reading the transcripts, coding the data with the help of qualitative software, analyzing the data for themes and subthemes, interpreting the themes, and devising the meaning of the themes.26 Initial codes were categorized and compared to determine recurrent themes. Three members of the research team independently reviewed the transcripts, extensively discussed the content, and developed consensus around the identified themes. Critical and rigorous steps were taken throughout data collection and analysis to ensure the credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability of the qualitative data.27-29 In addition, elements of the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research checklist were used to strengthen the data collection, analysis, and reporting process.30