Gastrointestinal cancers: new standards of care from landmark trials

Received for publication October 2, 2017

Published online ahead of print March 28, 2018

Correspondence

David H Henry, MD; David.Henry@uphs.upenn.edu;

Daniel G Haller, MD, FACP, FRCP; Daniel.Haller@uphs.upenn.edu

Disclosures The authors report no disclosures/conflicts of interest.

Citation JCSO 2018; 16(2): e117-e122

©2018 Frontline Medical Communications

doi https://doi.org/10.12788/jcso.0377

Listen to the audio here

Submit a paper here

DR HENRY I am Dr David Henry, the Editor-in-Chief of

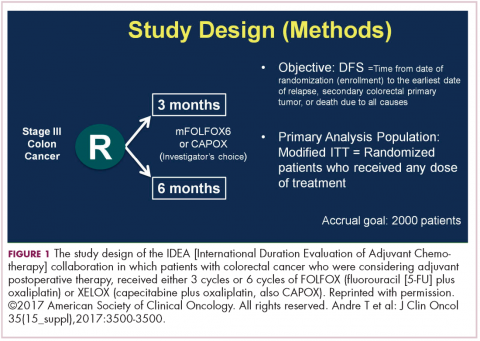

DR HALLER The IDEA collaboration was the brainchild of the late Dan Sargent, a biostatistician who was at the Mayo Clinic. It was his idea, since 6 international groups were all testing the same question of 3 months for oxaliplatin to 6 months of oxaliplatin, to combine the data in an individual patient database – which is the best way to do it – so there were these six trials that were all completed.

,Three of them were individually reported at ASCO this year, and then the totality was presented at the plenary session – the first time in 12 years that a gastrointestinal (GI) cancer trial made the plenary session. The whole point, obviously, is neuropathy. With 6 months of FOLFOX or XELOX, about 13% or more patients will develop grade 3 neuropathy, even if people stop short of the full-cycle length, and that is a big deal for the 50,000 patients or so who get adjuvant therapy. At the plenary session, the data were presented and the next day three individual trials were presented and discussed by Jeff Meyerhardt (of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston).

There were 6 different trials: a few included rectum, some included stage II, some used CAPOX and FOLFOX-4 or 6. The only trial that used only FOLFOX was the Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) trial in the United States (US). There was a lot of heterogeneity, but when Dan was around, I asked him whether that was a problem, and he said on the contrary, was a better thing because it allowed for real-life practice.

The primary endpoint of the study was to look for noninferiority of 3 months versus 6 months of treatment. The noninferiority margin was at a hazard ratio of 1.12, so they were willing to barter down a few percentage points from benefit. If you looked at the primary disease-free survival analysis, the hazard ratio was 1.07, which was an absolute difference of 0.9%, favoring 3 months of therapy. But because the hazard ratio crossed the 1.12 boundary, it was considered inconclusive and not proven.

If you looked at the regimens, CAPOX outperformed FOLFOX. That’s a regimen we don’t do much in the US. We tend to use more FOLFOX, but CAPOX looked better. What they then did was look at the different subsets of patients, and the subsets that it was obviously as good in was the group that had T1-3N1 disease, where 3 months of therapy was clearly just as good as 6 months of therapy, with only a 3% risk of grade 3 neuropathy.

DR HENRY That would be one to three nodes?

DR HALLER Exactly. That’s about 50% of patients. In the T4N2 patients, neither regimen did very well and the 3-year disease-free survival was in the range of 50%, which is clearly unacceptable. Jeff discussed two things. Why could CAPOX be better? If you do the math, when you do CAPOX, you get more oxaliplatin during the first few months of therapy, because it’s 130 mg every 3 weeks, rather than 85 mg every 2 weeks. His conclusion was, “for my next patient who has T4N2 disease, I’ll offer 6 months of FOLFOX.” The study that really need