Hallmark tumor metabolism becomes a validated therapeutic target

Citation JCSO 2018;16(1):e47-e52

©2018 Frontline Medical Communications

doi https://doi.org/10.12788/jcso.0389

Submit a paper here

The Warburg paradox

Although the molecular mechanisms underlying the Warburg effect have been revealed to some extent, why cancer cells would choose to use such an energy-inefficient process when they have such high energy demands, remains something of a paradox. It’s still not entirely clear, but several explanations that are not necessarily mutually exclusive have been proposed and relate to the inherent benefits of glycolysis and might explain why cancer cells favor this pathway despite its poor energy yield. First, ATP is produced much more rapidly through glycolysis than oxidative phosphorylation, up to 100 times faster. Thus, using glycolysis is a trade-off, between making less energy and making it more quickly.

Second, cancer cells require more than just ATP to meet their metabolic demands. They need amino acids for protein synthesis; nucleotides for DNA replication; lipids for cell membrane synthesis; nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH), which helps the cancer cell deal with oxidative stress; and various other metabolites. Glycolysis branches off into other metabolic pathways that generate many of these metabolites. Among these branched pathways is the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP), which is required for the generation of ribonucleotides and is a major source for NADPH. Cancer cells have been shown to upregulate the flux of glucose into the PPP to meet their anabolic demands and counter oxidative stress.

Third, the lactic acid produced through glycolysis is actively exported from tumor cells by monocarboxylate transporters (MCTs). This creates a highly acidic tumor microenvironment, which can promote several cancer-related processes and also plays a role in tumor-induced immunosuppression, by inhibiting the activity of tumor-infiltrating T cells, reducing dendritic cell maturation, and promoting the transformation of macrophages to a protumorigenic form.2,4,6

Beyond the Warburg effect

Although the focus has been on glucose metabolism and glycolysis, it has been increasingly recognized that many different metabolic pathways are altered. Fundamental changes to the metabolism of all 4 major classes of macromolecules – carbohydrates, lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids – have been observed, encompassing all aspects of cellular metabolism and enabling cancer cells to meet their complete metabolic requirements. There is also evidence that cancer cells are able to switch between different metabolic pathways depending on the availability of oxygen, their energetic needs, environmental stresses, and many other factors. Certainly, there is significant heterogeneity in the metabolic changes that occur in tumors, which vary from tumor to tumor and even within the same tumor and across the lifespan of a tumor as it progresses from an early stage to more advanced or metastatic disease.

The notion of the Warburg effect as a universal phenomenon in cancer cells is now being widely disregarded. Many tumors continue to use oxidative phosphorylation, particularly slower growing tumors, to meet their energy needs. More recently a “reverse” Warburg effect was described, whereby cancer cells are thought to influence the metabolism of the surrounding stromal fibroblasts and essentially outsource aerobic glycolysis to these cells, while performing energy-efficient oxidative phosphorylation themselves (Figure 2).5,15,16

There is thought to be a “lactate shuttle” between the stromal and cancer cells. The stromal cells express high levels of efflux MCTs so that they can remove the subsequently high levels of lactate from the cytoplasm and avoid pickling themselves. The lactate is then shuttled to the cancer cells that have MCTs on their surface that are involved in lactate uptake. The cancer cells oxidize the lactate back into pyruvate, which can then be used in the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle to feed oxidative phosphorylation for efficient ATP production. This hypothesis reflects a broader appreciation of the role of the microenvironment in contributing to cancer metabolism.17,18

An improved holistic understanding of cancer cell metabolism has led to the recognition of altered cancer metabolism as one of the hallmark abilities required for transformation of a normal cell into a cancerous one. It is categorized as “deregulation of bioenergetics” in the most up to date review of the cancer hallmarks.19 It has also begun to shape the therapeutic landscape as new drug targets have emerged.

IDH inhibitors first to market

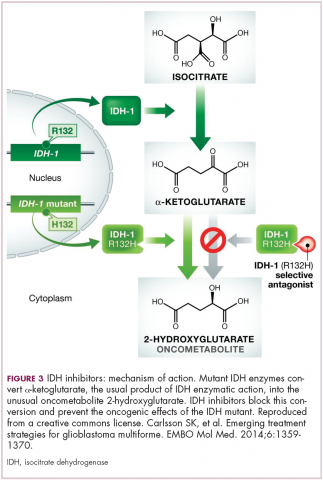

A number of new metabolically-targeted treatment strategies are being developed. Most promising are small molecule inhibitors of the isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) enzymes. These enzymes play an essential role in the TCA cycle, catalyzing the conversion of isocitrate to alpha-ketoglutarate, generating carbon dioxide and NADPH. Recurrent mutations in the IDH1 and IDH2 genes have been observed in several different types of cancer, including glioma, acute myeloid leukemia (AML), and cholangiocarcinoma.

IDH mutations are known as neomorphic mutations because they confer a new function on the altered gene product. In this case, the mutant IDH enzyme converts alpha-ketoglutarate further into D-2-hydroxyglutarate (D-2HG). This molecule has a number of different effects that promote tumorigenesis, including fostering defective DNA repair (Figure 3).20,21

Intriguing research presented at the American Association of Cancer Research Annual Meeting revealed that IDH mutations may make cancer cells more vulnerable to poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibition, likely as a result of defects in homologous recombination pathways of DNA repair.22The pursuit of IDH as a potential therapeutic target has yielded the first regulatory approval for a metabolically targeted anticancer therapy. In August 2017, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved enasidenib, an IDH2 inhibitor, for the treatment of relapsed or refractory AML with an IDH2 mutation. It was approved in combination with a companion diagnostic, the RealTime IDH2 Assay, which is used to detect IDH2 mutations.

The approval was based on a single-arm trial in which responses occurred in almost a quarter of the 199 patients treated with 100 mg oral enasidenib daily. After a median follow-up of 6.6 months, 23% of the patients experienced a complete response or a complete response with partial hematologic recovery lasting a median of 8.2 months. The most common AEs were nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, elevated bilirubin levels, and reduced appetite.23

Several other IDH inhibitors are also showing encouraging efficacy. Ivosidenib is an IDH1 inhibitor and the results of a phase 1 study in patients with cholangiocarcinoma were recently presented at a leading conference. Escalating doses of ivosidenib (100 mg twice daily to 1,200 mg once daily) were administered to 73 patients (as of December 2016). The confirmed partial response (PR) rate was 6%, the rate of stable disease was 56%, and PFS at 6 months was 40%. There were no dose-limiting toxicities (DLTs) and treatment-emergent AEs included fatigue, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, decreased appetite, dysgeusia, and QT prolongation.24

Another study of ivosidenib was presented at the 2017 annual meeting of the Society for Neuro-Oncology. In that study, patients with glioma received daily doses of ivosidenib ranging from 300 mg to 900 mg. Two patients had a minor response, 83% had stable disease, and the median PFS was 13 months. There were no DLTs and most AEs were mild to moderate and included, most commonly, headache, nausea, diarrhea, and vomiting.25