Clinical presentation, diagnosis, and management of typical and atypical bronchopulmonary carcinoid

Carcinoid tumors account for about 1% of all lung tumors. Most patients remain asymptomatic, but if symptoms present they will depend on the tumor location, size, and pattern of growth. The distinction between typical and atypical carcinoid is based on histology. Atypical carcinoid tumors tend to have higher potential for local recurrence as well as distant metastasis. Surgery is the treatment of choice for locoregional disease, but there is no recognized standard of care for advanced lung carcinoids and successful management requires a multidisciplinary approach. The aim of this article is to provide an updated review of the most recent literature for the diagnosis and clinical management of lung carcinoids.

Accepted for publication July 14, 2017

Correspondence

Hamza Hashmi, MD; H0hash03@exchange.louisville.edu

Disclosures The authors report no disclosures/conflicts of interest.

Citation JCSO 2017;15(6):e303-e308

©2017 Frontline Medical Communications

doi https://doi.org/10.12788/jcso.0365

Submit a paper here

Somatostatin receptors (SSRs) are present in many tumors of neuroendocrine origin, including carcinoid tumors. These receptors interact with each other and undergo dimerization and internalization. SSTR subtypes (SSTRs) overexpressed in NETs are related to the type, origin, and grade of differentiation of tumor. The overexpression of an SSTR is a characteristic feature of bronchial NETs, which can be used to localize the primary tumor and its metastases by imaging with the radiolabeled SST analogues. Radionucleotide imaging modalities commonly used include single-photon–emission tomography and positron-emission tomography.

With regard to SSR scintigraphy testing, PET using Ga–DOTATATE/TOC is preferable to Octreoscan if it is available, because offers better spatial resolution and has a shorter scanning time. It has sensitivity of 97% and specificity of 92% and hence is preferable over Octreoscan in highly aggressive, atypical bronchial NETs. It also provides an estimate of receptor density and evidence of the functionality of receptors, which helps with selection of suitable treatments that act on these receptors.7

,

Tumor markers

Serum levels of chromogranin A in bronchial NETs are expressed at a lower rate than are other sites of carcinoid tumors, so its measurement is of limited utility in following disease activity in bronchial NETs.4,8

Bronchoscopy

About 75% of pulmonary carcinoids are visible on bronchoscopy. The bronchoscopic appearance may be characteristic but it is preferable that brushings or biopsy be performed to confirm the diagnosis. For central tumors endobronchial; and for peripheral tumors, CT-guided percutaneous biopsy is the accepted diagnostic approach. Cytologic study of bronchial brushings is more sensitive than sputum cytology, but the diagnostic yield of brushing is low overall (about 40%) and hence fine-needle biopsy is preferred. 8

A negative finding on biopsy should not produce a false sense of confidence. If a suspicion of malignancy exists despite a negative finding on transthoracic biopsy, surgical excision of the nodule and pathologic analysis should be undertaken.

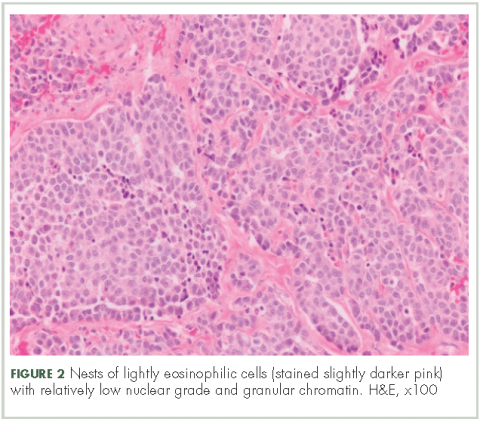

Histological findings

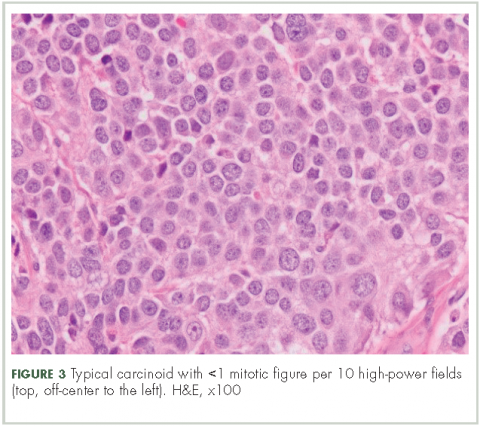

In typical carcinoid tumors, cells tend to group in nests, cords, or broad sheets. Arrangement is orderly, with groups of cells separated by highly vascular septa of connective tissue.9Individual cell features include small and polygonal cells with finely granular eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure 2). Nuclei are small and round. Mitoses are infrequent (Figure 3).

On electron microscopy, well-formed desmosomes and abundant neurosecretory granules are seen. Many pulmonary carcinoid tumors stain positive for a variety of neuroendocrine markers. Electron microscopy is of historical interest but is not used for tissue diagnosis for bronchial carcinoid patients.

Typical vs atypical tumors

In all, 10% of the carcinoid tumors are atypical in nature. They are generally larger than typical carcinoids and are located in the periphery of the lung in about 50% of cases. They have more aggressive behavior and tend to metastasize more commonly.2 Neither location nor size are distinguishing features. The distinction is based on histology and includes one or all of the following features:8,9

n Increased mitotic activity in a tumor with an identifiable carcinoid cellular arrangement with 2-10 mitotic figures per high-power field.9

n Pleomorphism and irregular nuclei with hyperchromatism and prominent nucleoli.

n Areas of increased cellularity with loss of the regular, organized architecture observed in typical carcinoid.

n Areas of necrosis within the tumor.

Ki-67 cell proliferation labeling index can be used to distinguish between high-grade lung NETs (>40%) and carcinoids (<20%), particularly in crushed biopsy specimens in which carcinoids may be mistaken for small-cell lung cancers. However, given overlap in the distribution of Ki-67 labeling index between typical carcinoids (≤5%) and atypical carcinoids (≤20%), Ki-67 expression does not reliably distinguish between well-differentiated lung carcinoids. The utility of Ki-67 to differentiate between typical and atypical carcinoids has yet to be established, and it is not presently recommended.9 Hence, the number of mitotic figures per high-power field of viable tumor area and presence or absence of necrosis continue to be the salient features distinguishing typical and atypical bronchial NETs.

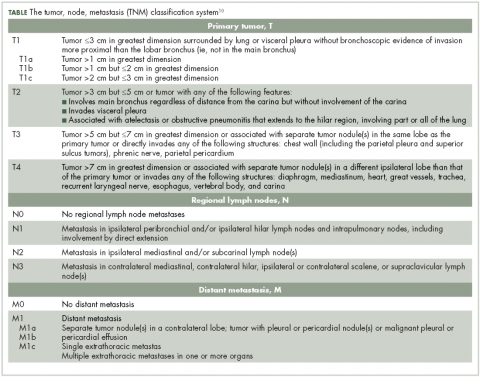

Staging10

Lung NETs are staged using the same tumor, node, metastasis (TNM) classification from the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) that is used for bronchogenic lung carcinomas (Table).

Typical bronchial NETs most commonly present as stage I tumors, whereas more than one-half of atypical tumors are stage II (bronchopulmonary nodal involvement) or III (mediastinal nodal involvement) at presentation.

Treatment

Localized or nonmetastatic and rescetable disease

Surgical treatment. As with other non–small-cell lung cancers (NSCLCs), surgical resection is the treatment of choice for early-stage carcinoid. The long-term prognosis is typically excellent, with a 10-year disease-free survival of 77%-94%.11, 12 The extent of resection is determined by the tumor size, histology, and location. For NSCLC, the standard surgical approach is the minimal anatomic resection (lobectomy, sleeve lobectomy, bilobectomy, or pneumonectomy) needed to get microscopically negative margins, with an associated mediastinal and hilar lymph node dissection for staging.13