Clinical presentation, diagnosis, and management of typical and atypical bronchopulmonary carcinoid

Carcinoid tumors account for about 1% of all lung tumors. Most patients remain asymptomatic, but if symptoms present they will depend on the tumor location, size, and pattern of growth. The distinction between typical and atypical carcinoid is based on histology. Atypical carcinoid tumors tend to have higher potential for local recurrence as well as distant metastasis. Surgery is the treatment of choice for locoregional disease, but there is no recognized standard of care for advanced lung carcinoids and successful management requires a multidisciplinary approach. The aim of this article is to provide an updated review of the most recent literature for the diagnosis and clinical management of lung carcinoids.

Accepted for publication July 14, 2017

Correspondence

Hamza Hashmi, MD; H0hash03@exchange.louisville.edu

Disclosures The authors report no disclosures/conflicts of interest.

Citation JCSO 2017;15(6):e303-e308

©2017 Frontline Medical Communications

doi https://doi.org/10.12788/jcso.0365

Submit a paper here

Carcinoid lung tumors represent the most indolent form of a spectrum of bronchopulmonary neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) that includes small-cell carcinoma as its most malignant member, as well as several other forms of intermediately aggressive tumors, such as atypical carcinoid.1 Carcinoids represent 1.2% of all primary lung malignancies. Their incidence in the United States has increased rapidly over the last 30 years and is currently about 6% a year. Lung carcinoids are more prevalent in whites compared with blacks, and in Asians compared with non-Asians. They are less common in Hispanics compared with non-Hispanics.1 Typical carcinoids represent 80%-90% of all lung carcinoids and occur more frequently in the fifth and sixth decades of life. They can, however, occur at any age, and are the most common lung tumor in childhood.1

Etiology and risk factors

Unlike carcinoma of the lung, no external environmental toxin or other stimulus has been identified as a causative agent for the development of pulmonary carcinoid tumors. It is not clear if there is an association between bronchial NETs and smoking.1 Nearly all bronchial NETs are sporadic; however, they can rarely occur in the setting of multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1.1

,Presentation

About 60% of the patients with bronchial carcinoids are symptomatic at presentation. The most common clinical findings are those associated with bronchial obstruction, such as persistent cough, hemoptysis, and recurrent or obstructive pneumonitis. Wheezing, chest pain, and dyspnea also may be noted.2 Various endocrine or neuroendocrine syndromes can be initial clinical manifestations of either typical or atypical pulmonary carcinoid tumors, but that is not common Cushing syndrome (ectopic production and secretion of adrenocorticotropic hormone [ACTH]) may occur in about 2% of lung carcinoid.3 In cases of malignancy, the presence of metastatic disease can produce weight loss, weakness, and a general feeling of ill health.

Diagnostic work-up

Biochemical test

There is no biochemical study that can be used as a screening test to determine the presence of a carcinoid tumor or to diagnose a known pulmonary mass as a carcinoid tumor. Neuroendocrine cells produce biologically active amines and peptides that can be detected in serum and urine. Although the syndromes associated with lung carcinoids are seen in about 1%-2% of the patients, assays of specific hormones or other circulating neuroendocrine substances, such as ACTH, melanocyte-stimulating hormone, or growth hormone may establish the existence of a clinically suspected syndrome.

Chest radiography

An abnormal finding on chest radiography is present in about 75% of patients with a pulmonary carcinoid tumor.1 Findings include either the presence of the tumor mass itself or indirect evidence of its presence observed as parenchymal changes associated with bronchial obstruction from the mass.

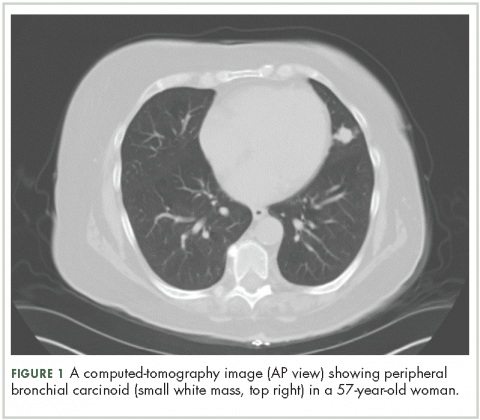

Computed-tomography imaging

High-resolution computed-tomography (CT) imaging is the one of the best types of CT examination for evaluation of a pulmonary carcinoid tumor.4 A CT scan provides excellent resolution of tumor extent, location, and the presence or absence of mediastinal adenopathy. It also aids in morphologic characterization of peripheral (Figure 1) and especially centrally located carcinoids, which may be purely intraluminal (polypoid configuration), exclusively extra luminal, or more frequently, a mixture of intraluminal and extraluminal components.

CT scans may also be helpful for differentiating tumor from postobstructive atelectasis or bronchial obstruction-related mucoid impaction. Intravenous contrast in CT imaging can be useful in differentiating malignant from benign lesions. Because carcinoid tumors are highly vascular, they show greater enhancement on contrast CT than do benign lesions. The sensitivity of CT for detecting metastatic hilar or mediastinal nodes is high, but specificity is as low as 45%.4

Typical carcinoid is rarely metastatic so most patients do not need CT or MRI imaging to evaluate for liver involvement. Liver imaging is appropriate in patients with evidence of mediastinal involvement, relatively high mitotic rate, or clinical evidence of the carcinoid syndrome.8 To evaluate for metastatic spread to the liver, multiphase contrast-enhanced liver CT scans should be performed with arterial and portal-venous phases because carcinoid liver metastases are often hypervascular and appear isodense relative to the liver parenchyma after contrast administration.4 An MRI is often preferred the modality to evaluate for metastatic spread to the liver because of its higher sensitivity.5

Positron-emission tomography

Although carcinoid tumors of the lung are highly vascular, they do not show increased metabolic activity on positron-emission tomography (PET) and would be incorrectly designated as benign lesions on the basis of findings from a PET scan. Fludeoxyglucose F-18 PET has shown utility as a radiologic marker for atypical carcinoids, particularly for those with a higher proliferation index with Ki-67 index of 10%-20%.6

Radionucleotide studies