The impact of combining human and online supportive resources for prostate cancer patients

Background Prostate cancer patients’ needs for information and support have been previously addressed by both mentoring and interactive services.

Objective To determine whether combining computer-based support with a human cancer mentor would benefit prostate cancer patients more than either intervention alone.

Methods Newly diagnosed prostate cancer patients from 3 centers were randomly assigned to receive either: a web-based system of information and support; or telephone and e-mail support from a trained cancer information mentor; or both interventions.

Results The combined condition improved several quality-of-life outcomes more than the individual interventions alone, but these results were few and scattered.

Limitations Offering Internet (computer) access to all potential subjects may have made some computer nonusers less likely to participate, biasing the sample toward relatively advantaged men.

Conclusions Combining human and computer-based interventions did not produce the expected much stronger benefits to patients. Given the costs involved, the computer-based system alone is likely preferable.

Funding/sponsorship Grant R01CA114539 from the National Cancer Institute

Accepted for publication February 8, 2017

Corresondence Robert P Hawkins, PhD; rhawkins@wisc.edu

Disclosures The authors report no disclosures/conflicts of interest.

Citation JCSO 2017;15(6):e321-e329

©2017 Frontline Medical Communications

doi https://doi.org/10.12788/jcso.0330

Related articles

Point of prostate cancer diagnosis experiences and needs of black men: the Florida CaPCaS study

Emergency department use by recently diagnosed cancer patients in California

Submit a paper here

Measures

Outcomes. This study included 4 measures of quality of life (an average of relevant portions of the World Health Organization’s Quality of Life (WHOQOL) measure, Emotional and Functional Well-being, and a prostate-cancer specific index, the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC). We also tested group differences on 5 more specific outcomes that were likely to be proximal rather than distal effects of the interventions: Cancer Information Competence, Health care Competence, Social Support, Bonding (with other patients), and Positive Coping.

Quality of life. Quality of life was measured by combining the psychological, social, and overall dimensions of the WHOQOL measures.23 Each of the 11 items was assessed with a 5-point scale, and the mean of those answers was the overall score.

Emotional well-being. Respondents answered 6 items of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – Prostate

Functional well-being. Respondents indicated how often they experienced each of the seven functional well-being subscale items of the FACT-Prostate.24

Prostate cancer patient functioning. We used the EPIC to measure of 3 of 4 domains of prostate cancer patient functioning: urinary, bowel, and sexual (omitting hormonal).25 The EPIC measures frequency and subjective degree of being a problem of several aspects in each domain. We then summed scores across the domains and transformed linearly to a 0-100 scale, with higher scores representing better functioning.

Cancer information competence. Five cancer information competence items, measured on a 5-point scale, assessed a participant’s perception about whether he could find and effectively and use health information, and were summed to create a single score.20

Social support. Six 5-point social support items assessed the informational and emotional support provided by friends, family, coworkers, and others, and were summed to create a single score.20

Health care competence. Five 5-point health care competence items assessed a patient’s comfort and activation level dealing with physicians and health care situations, and were summed to create a single score.20

Positive coping. Coping strategies were measured with the Brief Cope, a shorter version of the original 60-item COPE scale.26 Positive coping strategy, a predictor of positive adaptation in numerous coping contexts, was measured with the mean score of 4 scales (8 items in all): active coping, planning, positive reframing, and humor.

Bonding. Bonding with other prostate cancer patients was measured with five 5-point items about how frequently participants connected with and got information and support from other men with prostate cancer.27

User vs nonuser. Intent-to-treat analyses compared the assigned conditions. However, because CHESS use was self-selected and available at any time whereas mentor calls were scheduled and initiated by another person, the proportion actually using the interventions was quite different.

Since a participant assigned access to CHESS had to select the URL, even a single entry to the system was counted as use. Of 198 participants assigned to either the CHESS or CHESS+Mentor conditions, 43 (22%) never logged in and were classified as nonusers.

Because the mentor scheduled calls and attempted repeatedly to complete scheduled calls, the patient was in a reactive position, and the decision not to use the mentor’s services could come at the earliest at the end of a first completed call. However, after examining call notes and consulting with the mentors, it was clear that opting not to receive mentoring typically occurred at the second call. Furthermore, much (though not all) of the first call was typically taken up with getting acquainted and scheduling issues, so that defining “nonuse” as 2 or fewer completed calls was most faithful to what actually happened. Of 202 participants assigned access to a mentor, 16 (8%) were thus defined as nonusers.

Results

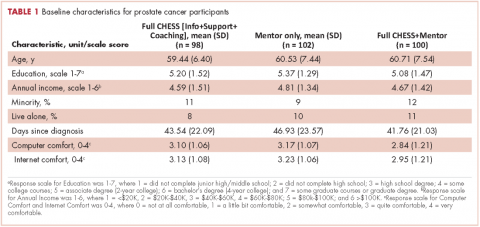

Overall, the participants were about 60 years of age and had some college education and middle-class incomes (Table 1). Only about 10% were minorities or lived alone, and their comfort using computers and the Internet was at or above the “quite comfortable” level. None of groups differed significantly from any other.

The 2 primary hypotheses of the study were that participants in the combined condition would manifest higher outcome scores than those with either intervention alone. Table 2 displays group means at 3 posttest intervals, controlling for theoretically chosen covariates (age, education, and minority status) and pretest levels of the dependent variable. The table also summarizes tests examining the hypotheses and the comparison of CHESS and Mentor conditions. The 4 quality-of-life scores appear first, followed by 5 more specific outcomes that are perhaps more proximal effects of these interventions.

The combined condition scored significantly higher than the CHESS-only condition on functional well-being at 3 months, on positive coping at 6 months, and on bonding at both 6 weeks and 6 months. The combined condition scored significantly higher than Mentor-only on health care competence and positive coping at 6 weeks, and on bonding at 6 months. This represents partial but scattered support for the hypotheses. And some comparisons of the combined condition with the Mentor-only condition showed reversals of the predicted relationship (although only cancer information competence at 3 months would have reached statistical significance in a 2-tailed test).

No directional hypotheses were made for the comparison of the 2 interventions (see Table 2 for the results of 2-tailed tests). Participants in the Mentor condition reported significantly higher functional well-being at 3 months, although there were 5 other comparisons in which the Mentor group scored higher at P < .10, and higher than the CHESS group on 22 of the 27 comparisons. Thus, it seemed that the Mentor condition alone might have been a somewhat stronger intervention than CHESS alone.