The impact of combining human and online supportive resources for prostate cancer patients

Background Prostate cancer patients’ needs for information and support have been previously addressed by both mentoring and interactive services.

Objective To determine whether combining computer-based support with a human cancer mentor would benefit prostate cancer patients more than either intervention alone.

Methods Newly diagnosed prostate cancer patients from 3 centers were randomly assigned to receive either: a web-based system of information and support; or telephone and e-mail support from a trained cancer information mentor; or both interventions.

Results The combined condition improved several quality-of-life outcomes more than the individual interventions alone, but these results were few and scattered.

Limitations Offering Internet (computer) access to all potential subjects may have made some computer nonusers less likely to participate, biasing the sample toward relatively advantaged men.

Conclusions Combining human and computer-based interventions did not produce the expected much stronger benefits to patients. Given the costs involved, the computer-based system alone is likely preferable.

Funding/sponsorship Grant R01CA114539 from the National Cancer Institute

Accepted for publication February 8, 2017

Corresondence Robert P Hawkins, PhD; rhawkins@wisc.edu

Disclosures The authors report no disclosures/conflicts of interest.

Citation JCSO 2017;15(6):e321-e329

©2017 Frontline Medical Communications

doi https://doi.org/10.12788/jcso.0330

Related articles

Point of prostate cancer diagnosis experiences and needs of black men: the Florida CaPCaS study

Emergency department use by recently diagnosed cancer patients in California

Submit a paper here

Study goals and hypotheses

Given the success of the 2 aforementioned approaches, we wanted to compare how CHESS and ongoing contact with a human cancer information mentor in patients with prostate cancer would affect both several general aspects of quality of life and 1 specific to prostate cancer. We also examined differences in the patients’ information competence, quality of life, and social support. There was no a priori expectation that one intervention would be superior to the other, but any differences found could be important to policy decisions, given their quite-different cost and scalability.

More importantly, the primary hypothesis of the study was that patients with access to both CHESS and a mentor would experience substantially better outcomes than those with access to either intervention alone, because each had the potential to enhance the other’s benefits. For example, a patient could read CHESS material and come to the mentor much better prepared. By referring the user to specific parts of CHESS for basic information, the mentor could use calls to address more complex issues, or help interpret and evaluate difficult issues. In addition, because CHESS provides the mentor information about changes in the patient’s treatments, symptoms, and CHESS use, in the combined condition the cancer information mentor can know much more about the patient than when working alone. We also expected that the mentor would stimulate the kind of diverse use of CHESS services we have found to be most effective

Because both mentoring and CHESS have consistently produced positive quality of life effects on their own, compared to controls, there is no reasonable expectation that negative effects of a combined condition could occur and should be tested for. Thus, the study was powered for 1-tailed significance in the comparison between the combined condition and either intervention alone, a procedure used consistently in previous studies of CHESS components or combined conditions. However, since the research question comparing the 2 interventions alone had no such strong history it was tested 2-tailed.

Methods

Recruitment

Study recruitment was conducted from January 1, 2007 to September 30, 2008 at the University of Wisconsin’s Paul P Carbone Comprehensive Cancer Center in Madison, Hartford Hospital’s Helen and Harry Gray Cancer Center in Hartford, Connecticut, and The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

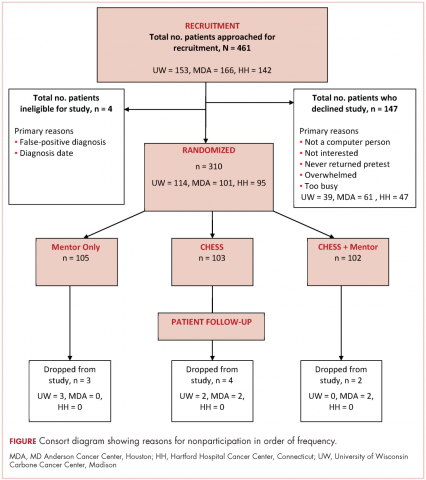

A total of 461 patients were invited to participate in the study. Of those patients, 147 declined to participate, 4 were excluded, and 310 were randomized to access to CHESS only, access to a human mentor only, or access to CHESS and a mentor (CHESS+Mentor) during the 6-month intervention period, which provided adequate power (>.80) for effects of moderate size (Figure 1). Randomization was done with a computer-generated list that site study managers accessed on a patient-by-patient basis, with experimental conditions blocked within sites.

Recruitment was done by posting brochures about the study at the relevant locations and devising standardized recruitment scripts for clinical staff to use when talking to patients about the study. Staff at all sites invited patients they thought might be eligible to learn more about the study. As appropriate, staff members then reviewed informed consent and HIPAA information, explained the interventions, answered patient questions, obtained written consent, collected complete patient contact and computer access information, and provided patients the baseline questionnaires.

The standard inclusion criteria were: men older than 17 years, being able to read and understand English, and being within 2 months of a diagnosis of primary prostate cancer (stage 1 or 2) at the time of recruitment. Despite the 2-month window, few men had begun treatment before pretest. Only 9 of the 310 participants reported having already had surgery (7 prostatectomies, 2 implants), so participants may be fairly characterized as beginning the study in time to benefit from interventions during most stages of their experience with prostate cancer.

Interventions

To provide an equal baseline, all of the participants were given access to the Internet, which is becoming a de facto standard for information access. Internet access charges were paid for all participants during the 6-month intervention period, and computers were loaned to those who did not have a personal computer. All of the participants were offered training on using the computer, particularly with Google search procedures so that they could access resources on prostate cancer.