Prehabilitation for lymphedema in head and neck cancer patients at a community cancer center

Patients with head and neck cancer often develop morbidities as a result of their treatment with surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy. One of the most prevalent side effects of the treatment is lymphedema, the accumulation of interstitial fluid in tissues that have inadequate lymph drainage. Secondary lymphedema, an acquired abnormality in the lymphatic network, is commonly caused by cancer and/or its treatment. Lymphedema is both under-recognized and under-treated in head and neck cancer. While recent advances in radiation therapy techniques have resulted in a corresponding drop in other treatment-related morbidities, an estimated 50% of treated head and neck cancer patients will develop lymphedema. Indeed, at some places the incidence is much higher, at 75%, following treatment with surgery and radiation. Clearly, there is an unmet need to recognize and treat lymphedema in head and neck cancer patients. This article describes an early intervention prehabilitation program that was established for the early identification and treatment of patients at risk of lymphedema and compares the observed outcomes before and after the initiation of the program.

Accepted for publication April 21, 2017

Correspondence Ian V Hutchinson, PhD, DSc;

Ian.Hutchinson@providence.org

Disclosures The authors report no disclosures/conflicts of interest.

Citation JCSO 2017;15(3):e127-e134

©2017 Frontline Medical Communications

doi https://doi.org/10.12788/jcso.0345

Related article

Women with self-reported lower-limb lymphedema after treatment for gynecological cancers...

Submit a paper here

Site of the tumor

The literature suggests that patients with a primary tumor in the throat are at increased risk for lymphedema.5 The American Cancer Society has defined cancers of the oropharynx (throat) as including the base of the tongue (back third of the tongue), the soft palate, the tonsils, and the side and back walls of the throat.18 In our head and neck cancer cohort, patients with primary tumors of the oropharnyx were, perhaps, more susceptible to lymphedema (P = .044, Table 3). By contrast, in our cohort of patients, those with nasopharyngeal, hypopharyngeal, and parotid gland tumors were significantly less likely to develop lymphedema (Ps = .017, .04, .012, respectively).

No surgery

Half of our patients (n = 95) were not treated with surgery. In the patients who did not have surgery, 25 (26%) developed lymphedema, whereas 70 (74%) did not. Hence, although the incidence of lymphedema was significantly lower in patients who did not have surgery (P = .015), lymphedema did develop in patients who did not have a surgical procedure.

Resection of primary tumor without neck dissection

Of the 64 patients who had surgery, but without neck dissection, 35 (55%) developed external lymphedema. Compared with the no-surgery patients, the doubling of the incidence (from 26% to 55%) was highly significant (P = .0004). These findings are compatible with the literature reports that surgery increases the incidence of lymphedema, which is not surprising because surgery and subsequent scarring is known to compromise the lymphatic system.

,Resection of primary tumor with neck dissection

The incidence of external lymphedema was increased to 69% when patients were subjected to both surgery and neck dissection. Compared with the June 2008-June 2015 cohort, there was a significant increase in the incidence of lymphedema in the neck dissection group (P = .007). Neck dissection involves the removal of lymph nodes and disruption of the lymphatic vessels, so it is not surprising that there is a higher incidence of external lymphedema. In our practice, neck dissections increased in frequency every year from June 2008 until December 2011, when 8 patients underwent neck dissections, 6 (75%) of whom developed lymphedema. Since January 2012, when the prehabilitation program was implemented, the number of neck dissections have declined, with more patients receiving chemoradiation and surgery being reserved for surgery. Hamoir and colleagues have reported that neck dissection is no longer justified unless there is clinically residual disease in the neck.19

Radiation

Lymphedema occurred in patients regardless of the dose of radiation received. Although the incidence of lymphedema seemed to be higher in patients who received more than 60 cGy, that difference was not statistically significant (Table 3). We had expected a relationship between radiation damage and greater lymphedema, but that was not evident in our patients.

Chemotherapy

The majority of patients (n = 131, 69%) received chemotherapy. The exposure to chemotherapy was not correlated with the risk of external lymphedema in our cohort of patients, with 58 of the 131 treated patients (44%) developing lymphedema, compared with 73 (56%) of treated patients who did not (Table 3).

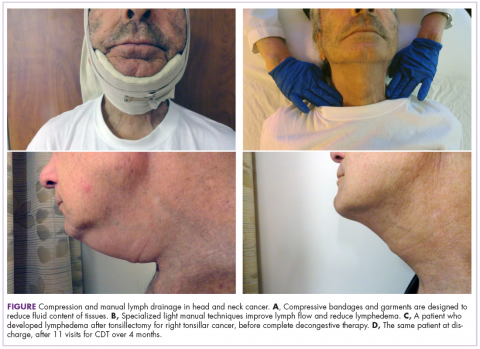

Complete decongestive therapy

All patients with documented lymphedema were evaluated for complete decongestive therapy (CDT). Contraindications to CDT included congestive heart failure, renal failure, acute infection, peripheral artery disease, upper-quadrant deep vein thrombosis, and carotid artery stenosis. Eligible patients were referred to a certified lymphedema therapist for CDT. As the program evolved, patients at risk for lymphedema were referred for CDT early on, usually at the time of diagnosis, to improve early identification and surveillance of lymphedema.

CDT included manual lymph drainage,

Patients’ responses to CDT were documented with digital photographs that were taken at each visit and, more recently, use of the NDI.

Communication and education

The head and neck cancer nurse navigator attends the cancer center’s multidisciplinary head and neck tumor board, which has representation from otolaryngology, diagnostic radiology, pathology, radiation oncology, medical oncology, reconstructive surgery, oncology rehabilitation (physical/occupational therapist), dietary services, speech pathology, social services and clinical research. This regular contact allows for earlier awareness about which patients are at greater risk for developing lymphedema, thus enabling early intervention (and patient education) in a timely manner.