Prehabilitation for lymphedema in head and neck cancer patients at a community cancer center

Patients with head and neck cancer often develop morbidities as a result of their treatment with surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy. One of the most prevalent side effects of the treatment is lymphedema, the accumulation of interstitial fluid in tissues that have inadequate lymph drainage. Secondary lymphedema, an acquired abnormality in the lymphatic network, is commonly caused by cancer and/or its treatment. Lymphedema is both under-recognized and under-treated in head and neck cancer. While recent advances in radiation therapy techniques have resulted in a corresponding drop in other treatment-related morbidities, an estimated 50% of treated head and neck cancer patients will develop lymphedema. Indeed, at some places the incidence is much higher, at 75%, following treatment with surgery and radiation. Clearly, there is an unmet need to recognize and treat lymphedema in head and neck cancer patients. This article describes an early intervention prehabilitation program that was established for the early identification and treatment of patients at risk of lymphedema and compares the observed outcomes before and after the initiation of the program.

Accepted for publication April 21, 2017

Correspondence Ian V Hutchinson, PhD, DSc;

Ian.Hutchinson@providence.org

Disclosures The authors report no disclosures/conflicts of interest.

Citation JCSO 2017;15(3):e127-e134

©2017 Frontline Medical Communications

doi https://doi.org/10.12788/jcso.0345

Related article

Women with self-reported lower-limb lymphedema after treatment for gynecological cancers...

Submit a paper here

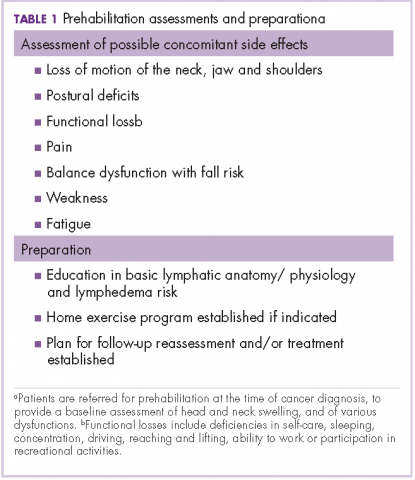

The nurse navigator sits in on each radiation oncology consultation and aids in “navigating” patients through their treatment. The nurse ensures that each patient is referred to different ancillary services from the outset, such as seeing a dietician, social worker, physical/occupational therapist and certified lymphedema therapist, speech pathologist, and financial assistance advisor, if necessary (Table 1).

Assessment of lymphedema

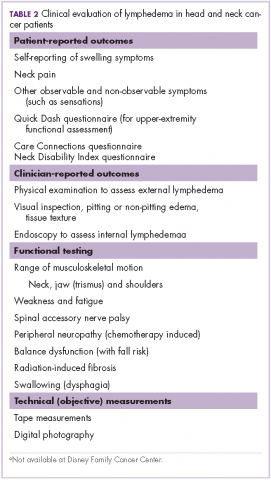

Measurement of head and neck lymphedema is a challenge.10 In our program, the physical therapy assessment also includes the evaluation of several other morbidities associated with head and neck cancer and its treatment, such as range of motion, weakness, fatigue, radiation fibrosis, balance dysfunction, and risk of falling (Table 2).

,Patient-reported outcomes are essential to fully capture observable and unobservable symptoms (eg, sensations) as well as the functional impacts of lymphedema.10 In addition to lymphedema, there are many other morbidities that may be assessed on the basis of patient-reported outcome tools, such as upper extremity function with QuickDASH.13 At our clinic for head and neck cancer patients we use the Neck Disability Index (NDI)14 and Care Connections (CC)15 survey for the patient-reported outcomes. The Quick DASH, NDI, and CC tools all assess standard functional outcomes that are not specific to lymphedema, but are useful in documenting changes related to lymphedema. We initially used the CC survey and later transitioned to using the NDI. Neck pain is common with lymphedema in the head and neck region, and the NDI is a valid, reliable, responsive and internally consistent clinical tool to measure self-reported disability in patients with neck pain.16 These questionnaires were completed by the patients at their initial assessment, at reassessment, and at time of discharge.

Although objective criteria for external lymphedema have not been established, simple measurements such as using a tape measure to record neck circumference, allow a useful longitudinal assessment. Digital photography may be effective in the documentation and subjective evaluation of changes of external lymphedema.10,17 However, there are some limitations with photography because although external photographs (including digital photography and three-dimensional imaging) can capture some features, such as changes in contours, symmetry, and changes in skin quality and color, they do not detect changes in skin and soft tissue texture and compliance (Table 3).10

Impact on clinical outcomes

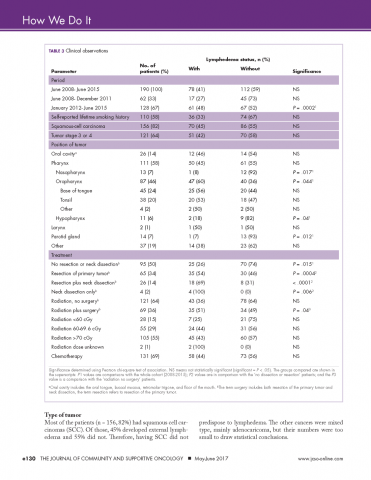

We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of 230 head and neck cancer patients who had been treated at our center between June 2008 and June 2015. Complete clinical data were available for 190 patients. The following information was extracted from each patient’s chart: whether they developed lymphedema, tumor stage, had surgery, radiation dose, type of chemotherapy given, their smoking history, if they had had a neck dissection and the primary site of the tumor (Table 3).

Incidence in different time periods. Of the 190 patients with complete records 78 (41%) were found to have lymphedema. These were all patients undergoing treatment for head and neck cancer during June 2008-June 2015. The prehabilitation program was initiated with the hiring of a nurse navigator for head and neck cancer, starting in January 2012. It is interesting to note that the incidence of lymphedema was 27% before the program was started, but after nurse navigator joined the team, the incidence increased significantly to 48% (P = .0002), in line with published expectations. This increase in recorded incidence may be attributable to the greater awareness of lymphedema intentionally fostered by the prehabilitation program.

Smoking history. Patients’ lifetime smoking history was retrieved from their medical records, based on their verbal admission of tobacco use. Most of the patients (n = 110) self-reported a history of smoking. Of those with a history of smoking, 36 (33%) developed external lymphedema after treatment for head and neck cancer, and 74 (67%) did not. However, this difference was not statistically significant. Hence, although smoking is a risk factor for head and neck cancer, it was not associated with the development of external lymphedema in our cohort of patients.

Type of tumor

Most of the patients (n = 156, 82%) had squamous cell carcinomas (SCC). Of those, 45% developed external lymphedema and 55% did not. Therefore, having SCC did not predispose to lymphedema. The other cancers were mixed type, mainly adenocaricoma, but their numbers were too small to draw statistical conclusions.

Stage of the tumor

About two thirds of the patients (n = 121, 64%) had stage 3 or 4 cancer. However, treatment of more advanced cancers was not associated with lymphedema development.