Prevention and treatment options for mTOR inhibitor-associated stomatitis

Inhibitors of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) are approved for treatment of various advanced solid tumors (renal cell carcinoma, neuroendocrine tumors, breast cancer). mTOR inhibitor-associated stomatitis (mIAS), a frequent, early-onset side effect of this drug class, can be dose limiting and diminish patient quality of life. This systematic review describes clinical presentation and pathophysiology of mIAS and reviews its prevention and treatment. Published literature on mTOR inhibitors and their side effects, and their prevention and treatment were reviewed. Preventative and management strategies under evaluation in clinical trials were also reviewed. The majority of patients develop a mild form of stomatitis that does not interfere with treatment of their disease. A minority of patients can develop moderate to severe mIAS that can be managed with treatment modification or discontinuation, but these approaches may have an impact on disease outcome. mIAS is a relatively recent phenomenon, so evidence-based preventive and therapeutic measures are not yet available – although under active investigation – and current management is based largely on collective experience with chemotherapy- or radiation-induced oral mucositis and aphthous ulcers. Expert opinion and clinical experience from managing oral mucositis and apthous ulcers suggest that management of mIAS should focus on three major approaches: prevention, early aggressive treatment, and, when needed, more aggressive pain management. Early recognition and diagnosis of mIAS facilitate early intervention to limit potential sequelae of mIAS and minimize the need for mTOR inhibitor dose reduction and interruption. Funding for manuscript development was provided by Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation.

Accepted for publication February 17, 2017

Correspondence Kavitha J Ramchandran, MD; kavitha@stanford.edu

Disclosures The authors report no disclosures/conflicts of interest.

Citation JCSO 2017;15(2):74-81

©2017 Frontline Medical Communications

doi https://doi.org/10.12788/jcso.0335

Submit a paper here

Differential diagnosis of mIAS should be made based on physical examination and medical history, with consideration given to appearance of lesions (number, size, and location), current infection status, and current medications. Specific diagnostic testing should be conducted to confirm a coexisting or alternative cause of oral lesions.17

Although there are many different scales for grading mIAS severity, the most commonly used are the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (based on patient function, symptoms, and intervention needs) and the World Health Organization oral mucositis scales (based on symptoms, clinical presentation, and interference with patient function).20-22 These scales distinguish between mild lesions (grade 1/2) and moderate to severe lesions (grade 3/4) that cause significant pain or interfere with oral intake.

Pathophysiology of mIAS

The pathophysiology mIAS is incompletely understood. The ubiquitous role of the PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway in regulating broad cellular functions suggests that mTOR inhibition is likely to have wide-ranging effects on many biological processes. It is not known whether disruption of one or more processes – or upsetting the balance of mTOR activities – underlies the formation of mIAS.

,Differences between mIAS and oral mucositis, including clinical presentation and concomitant toxicities,16,23 suggest that the two types of oral lesions are fundamentally distinct. This distinction is supported by animal studies in which mTOR inhibition was found to almost completely prevent the appearance of oral mucositis in irradiated mice. The protective effect of mTOR inhibition is mediated through suppression of oxidative stress generated by radiation therapy.24

Although mIAS and recurrent aphthous ulcers share some similarities, it is not clear whether they also share a common pathophysiology. Recent studies suggest that patients with recurrent aphthous ulcers have immune dysfunction that leads to excessive immune response to normally innocuous substrates in the oral mucosa.25 mTOR inhibition can have proinflammatory activity by promoting autophagy, a process that stimulates antigen presentation and activation of T cells that produce proinflammatory cytokines.26 It is interesting to note that the incidence of stomatitis in patients receiving sirolimus after kidney transplant is relatively low, 3%-20%.5 Sirolimus is administered in combination with other immunosuppressants, namely cyclosporine and corticosteroids, so it suggests that concomitant use of a steroid-based regimen may have a preventive or therapeutic effect. However, posttransplant sirolimus is typically administered at relatively low doses, which might account in part for the lower incidence of mIAS observed. Ongoing clinical studies of steroid-based mouthwashes in patients receiving everolimus should shed light on this.

Other study findings have shown that inhibition of the PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling pathway affects skin wound healing,27,28 which raises the possibility that mIAS may stem from a diminished capacity to repair physical injuries to the oral mucosa. More research is needed to elucidate the pathophysiology of mIAS.

Preventive measures for patients initiating mTOR inhibitor treatment

There are preventive measures for mIAS that have not yet been backed up with evidence-based findings, although several clinical studies that are underway aim to address this gap (Table 2). The hypotheses about the pathophysiology of mIAS suggest that certain preventive and therapeutic interventions might be effective against mIAS. For example, two studies are evaluating the use of steroid-based mouthwashes in patients receiving everolimus, based on the hypothesis that mIAS may arise from an inflammatory process; another study will evaluate a mucoadhesive oral wound rinse, based on the hypothesis that wound protection might prevent mIAS. Glutamine suspension is also under evaluation as it is understood to have wound-preventative and tissue-repair properties, and another study is focused on dentist-guided oral management. Recent results of one of these trials (SWISH),29 reported that preventative care with a dexamethasone mouthwash 3-4 times a day significantly minimized or prevented the incidence of all grades of stomatitis in women receiving everolimus plus exemestane therapy for advanced/metastatic breast cancer compared with the incidence of stomatitis observed in a previously published phase 3 trial (BOLERO-2)30,31 of everolimus plus exemestane in the same patient population. Results from several other studies are expected soon.

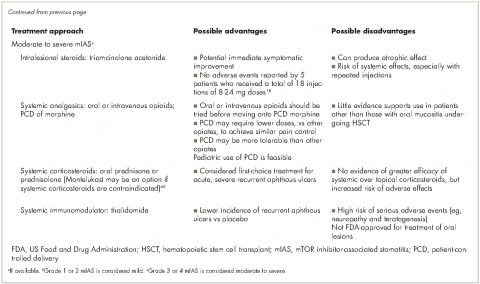

Current approaches to mIAS prevention are based largely on clinical experience with chemotherapy- or radiation-induced oral mucositis (Table 3).13,32 Preventive measures use three main strategies: establish and maintain good routine oral care; modify diet to avoid potentially damaging foods; and improve patient education about mIAS. In regard to patient education, numerous studies have reported that establishing an institutional protocol for oral care helped reduce the incidence of chemotherapy- or radiation-induced oral mucositis.33-40 An ongoing clinical study that will randomize patients to receive oral care education from oral surgeons or instruction on brushing only (NCT02376985) is investigating whether having an oral care protocol holds for patients with mIAS. The hypothesis is that focusing attention on oral care and educating patients to recognize the onset of mIAS facilitates early detection and promotes early intervention.