Utilization of Primary Care Physicians by Medical Residents: A Survey-Based Study

Comparison of Residents With and Without a PCP

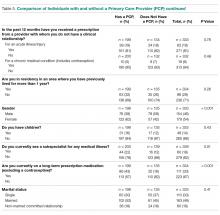

Important differences were noted between residents who had a PCP versus those who did not (Table 5). For example, a higher percentage of residents with a PCP indicated they had been diagnosed with a chronic medical illness (n = 55, 28% vs. n = 22, 16%; P = 0.01) or a chronic mental health condition (n = 34, 17% vs. n = 11, 8%; P = 0.02) before residency. Additionally, a higher percentage of residents with a PCP (n = 70, 35% vs. n = 25, 18%; P = 0.001) reported experiencing medical events such as pregnancy, hospitalization, surgery, ED visit, or new diagnosis of a chronic medical illness during residency. Finally, a higher percentage of respondents with a PCP stated that they had visited a subspecialist for a medical illness (n = 44, 22% vs. n = 16,12%; P = 0.01) or were taking long-term prescription medications (n = 86, 43% vs. n = 25; 18%; P < 0.001). When comparing PGY-1 to PGY-2–PGY-4 residents, the former reported having established a medical relationship with a PCP significantly less frequently (n = 56, 43% vs. n = 142, 70%; P < 0.001).

Discussion

This survey-based study of medical residents across the United States suggests that a substantial proportion do not establish relationships with PCPs. Additionally, our data suggest that despite establishing care, few residents subsequently visited their PCP during training for wellness visits or routine care. Self-reported rates of chronic medical and mental health conditions were substantial in our sample. Furthermore, inappropriate self-prescription and the receipt of prescriptions outside of a medical relationship were also reported. These findings suggest that future studies that focus on the unique medical and mental health needs of physicians in training, as well as interventions to encourage care in this vulnerable period, are necessary.

We observed that most respondents that established primary care were female trainees. Although it is impossible to know with certainty, one hypothesis behind this discrepancy is that women routinely need to access preventative care for gynecologic needs such as pap smears, contraception, and potentially pregnancy and preconception counseling [14,15]. Similarly, residents with a chronic medical or mental health condition prior to residency established care with a local PCP at a significantly greater frequency than those without such diagnoses. While selection bias cannot be excluded, this finding suggests that illness is a driving factor in establishing care. There also appears to be an association between accessing the medical system (either for prescription medications or subspecialist care) and having established care with a PCP. Collectively, these data suggest that individuals without a compelling reason to access medical services might have barriers to accessing care in the event of medical needs or may not receive routine preventative care [9,10].

In general, we found that rates of reported inappropriate prescriptions were lower than those reported in prior studies where a comparable resident population was surveyed [8,12,16]. Inclusion of multiple institutions, differences in temporality, social desirability bias, and reporting bias might have influenced our findings in this regard. Surprisingly, we found that having a PCP did not influence likelihood of inappropriate prescription receipt, perhaps suggesting that this behavior reflects some degree of universal difficulty in accessing care. Alternatively, this finding might relate to a cultural tendency to self-prescribe among resident physicians. The fact that individuals on chronic medications more often both received and wrote inappropriate prescriptions suggests this problem might be more pronounced in individuals who take medications more often, as these residents have specific needs [12]. Future studies targeting these individuals thus appear warranted.

Our study has several limitations. First, our sample size was modest and the response rate of 45% was low. However, to our knowledge, this remains among the largest survey on this topic, and our response rate is comparable to similar trainee studies [8,11,13]. Second, we designed and created a novel survey for this study. While the questions were pilot-tested with users prior to dissemination, validation of the instrument was not performed. Third, since the study population was restricted to residents in fields that participate in primary care, our findings may not be generalizable to patterns of PCP use in other specialties [6].