Metabolic Complications of HIV Infection

Screening and Monitoring of Hyperlipidemia

The most recent iteration of the DHHS primary care guidelines for the management of HIV-infected individuals recommends obtaining fasting (ideally 12 hours) lipid profiles upon initiation of care, and within 1 to 3 months of beginning therapy [12,13]. These initial levels, along with other elements of the patient’s history and calculation of risk may help determine whether lipid-lowering therapy is indicated, and if so, which therapy would be best. In general, after regimen switches or additions of either ARV or statin therapy, repeating fasting lipid levels 6 weeks later is recommended to gauge the effects of the switch. This is especially critical when interactions between ARVs and lipid-lowering therapies are possible. Some experts recommend performing annual screening of patients with normal baseline lipids or with well-controlled hyperlipidemia on therapy. Assessment of 10-year ASCVD risk is also recommended annually, in addition to baseline risk assessment, to determine the need and appropriateness of statin therapy [25]. The question of primary prevention in HIV has yet to be definitively answered. Small studies in this population have demonstrated that statins have the potential to slow progression of carotid intima media thickness and reduce noncalcified plaque volume [24]. An NIH/AIDS Clinical Trial Group–sponsored randomized clinical trial (“REPRIEVE”) is currently underway to address this question. More than 6000 HIV-infected men and women with no history of ASCVD at 100 sites in several countries are enrolled to assess the benefit of pitavastatin as primary prevention in this risk group [24]. Metabolized via glucuronidation primarily, as opposed to cytochrome p450 (CYP 3A4 isoenzyme), pitavastatin is thought to have fewer drug interactions with ARVs in general [6] (Table 2).

Relevant Drug-Drug Interactions

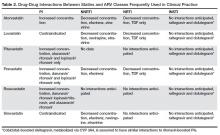

Deciding which statin to begin in HIV-infected patients depends on whether moderate- or high-intensity therapy is warranted and whether the potential for drug interaction with ARVs exists. Table 2 [6,12] depicts available statins and the potential for pharmacokinetic interaction with the primary ARV classes. Simvastatin and lovastatin are heavily metabolized via the CYP 3A4 pathway, resulting in the highest potential risk of interaction with CYP 3A4 inhibitors, such as the PIs, or inducers (eg, NNRTIs, in particular efavirenz) [6]. The former may inhibit metabolism of these statins, resulting in increased risk of toxicity, while co-administration with efavirenz, for example, may result in inadequate serum concentration and therefore inadequate lipid-lowering effects. Although less lipophilic, atorvastatin results in similar interactions with PIs and NNRTIs, and therefore low starting doses with close monitoring is recommended [6]. Fewer interactions have been noted with rosuvastatin, pravastatin, and pitavastatin, as these do not require CYP 3A4 for their metabolism and are thus less likely to be affected by ARVs. These therefore represent potentially safer first choices for certain patients on ARVs, although of these, only rosuvastatin is classified as a high-intensity statin [22,23] (Table 1). When compared directly to pravastatin 40 mg daily in patients receiving ritonavir-boosted PIs, rosuvastatin performed superiorly at 10 mg per day, resulting in more significant reductions in LDL and triglyceride levels [15]. Although it is eliminated largely unchanged through the kidney and liver, pravastatin has been reported to idiosyncratically interact with darunavir, resulting in potentially increased pravastatin levels and associated toxicity [25]. Treatment of pure hypertriglyceridemia in HIV-infected patients should begin with fibrates, which have little to no risk of interaction with most clinically relevant ARVs [6,10]. Alternatives to lower triglycerides include niacin and N-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids [25].

Case 1 Continued

The patient has an impressive response to his initial regimen of TDF/FTC plus boosted darunavir, with repeat CD4 count after 12 weeks of 275 (18%) cells/mm3 and an undetectable viral load (< 20 copies/mL). Other lab parameters are favorable and he is tolerating the regimen well without notable side effects. However, at his next visit, although his viral load remains undetectable, his triglyceride level has increased to 350 mg/dL, although other lipid parameters are comparable to the prior result. He complains of diffuse body aches, concentrated in large muscle groups of the extremities, and dark-colored urine. A creatine phosphokinase (CPK) level is elevated at 300 IU/L (normal, 22–269, negative MB fraction). Serum creatinine is 1.4 mg/dL (had been 1.1 mg/dL at baseline). Given he has done so well otherwise on these ARVs, he is reluctant to make any changes.

What drug-drug interaction is most likely causing this patient's problem, and how should it be managed?

This scenario is not uncommon in clinical practice, and changes to regimens are sometimes necessary in order to avoid drug interactions. Care must be taken to thoroughly review antiretroviral history and available resistance testing (in this case a relatively short history) in order to ensure a fully active and suppressive regimen is chosen. This description could be the result of an interaction between lipid-lowering therapy and ARVs resulting in increased relative concentrations of one drug or the other and therefore leading to toxicity. Given this possibility, and suboptimal control of hyperlipidemia, consideration should be given to switching both his ART and his statin therapy.

Safety and Potential Toxicities of Lipid-Lowering Therapy

Increased serum concentration of certain statins when co-administered with CYP 3A4 inhibitors like the PIs leads to heightened risk of statin-associated toxicities. In general, this includes muscle inflammation, leading to increases in serum CPK level and associated symptoms, including myalgias, myositis, or in extreme cases, rhabdomyolysis [6]. Although rare, this toxicity can be serious and may lead to acute renal injury if not recognized and managed appropriately. In theory, the potential for statin-associated hepatotoxicity may also be increased in patients receiving PIs, although this has not been borne out in clinical trials [26]. In fact, quite the opposite may be true, in that statins have been shown to improve liver function in patients with hepatitis C virus (HCV) coinfection and with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease [6,15].

Case 1 Conclusion

The patient does well on his new ARV regimen of TAF/FTC and dolutegravir, 2 pills once daily. He no longer requires TMP/SMX, as his CD4 count has been reliably above 200 cells/mm3 on several occasions. Serum creatinine is back down to baseline and CPK has normalized. Fasting lipids have improved since the switch, and he no longer has symptoms of myositis on rosuvastatin 10 mg daily.

Summary

Consideration of statin therapy is complicated by potential drug interactions with ARVs and associated toxicity. However, given known effects of ARVs on lipids, and of immune activation and inflammation related to the virus itself, these patients should be carefully evaluated for statin therapy for their anti-inflammatory and immune modulatory effects as much as for their lipid-lowering ability. Utilization of HIV infection and its therapies as additional cardiovascular risk factors when calculating 10-year risk deserves further consideration; forthcoming results of the REPRIEVE trial are certain to contribute valuable information to this field of study.

Case Patient 2

Initial Presentation and History

A 45-year-old female with history of HIV infection since 2008 presents to the office for new-onset diabetes, diagnosed 2 weeks ago. She has had symptoms of polyuria and polydipsia for the last 1 month. She denies diarrhea, nausea, vomiting or weight loss. She is currently on a regimen consisting of zidovudine/lamivudine plus lopinavir/ritonavir. There is no family history of diabetes. Her examination is unremarkable, including normal vital signs (weight 150 lb, blood pressure 114/70, heart rate 76) and no evidence of insulin resistance, including acanthosis nigricans or striae. Glycosylated hemoglobin level (HbA1c) is 8%. Creatinine and liver function tests are within reference ranges.

Do HIV-infected patients have a higher incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM)?

Prevalence of type 2 DM in HIV-infected patients varies between 2% to 14% [27]. This variation is due to the different cutoffs used for diagnosis, differences in cohorts studied, and how risk factors are analyzed [28–31]. In a recent nationally representative estimate of DM prevalence among HIV-infected adults receiving medical care in the United States in 2009–2010, the prevalence of DM was noted to be 10.3%. In comparison to the general adult US population, HIV-infected individuals have a 3.8% higher prevalence of DM after adjusting for age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, poverty-level, obesity, and HCV infection [27].

There is controversy over whether HIV infection itself increases the risk of type 2 DM, with some studies showing increased risk [28,32,33] and others showing no independent effect or an inverse effect [30,34,35]. Studies on the impact of ethnicity and race on prevalence of DM are limited [36].

Certain traditional risk factors (age, ethnicity, obesity) are still responsible for most of the increased risk of diabetes in the HIV-infected population [35,37]. HIV infection itself is associated with metabolic dysfunction, independent of ARV. In HIV-infected patients, impaired glucose metabolism is associated with altered levels of adipokines, increased adiponectin and soluble-tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 (sTNFR1) and decreased leptin [38,39]. HIV-associated alterations in CD4+ and CD8+ T cell function also impair glycolysis, which may adversely impact glucose metabolism [40].

Other contributing factors in HIV-infected patients are HCV co-infection [41], medications (atypical antipsychotics, corticosteroids), opiates, and low testosterone [42]. HCV co-infection may lead to hepatic steatosis and liver fibrosis, and increasing insulin resistance.

Recent genomic studies show several common single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with diabetes in the general population. In the Swiss HIV Cohort Study, SNPs accounted for 14% of type 2 DM risk variability, whereas ARV exposure accounted for 3% and age for 19% of the variability in DM [43].

ARVs also increase the risk of type 2 DM by both direct and indirect effects. Certain ARVs causes lipoatrophy [30] and visceral fat accumulation/lipohypertrophy [29,44]. PIs increase insulin resistance via effects on GLUT-4 transporter and decrease insulin secretion through effects on B cell function [45]. NRTIs (eg, stavudine, zidovudine and didanosine) can cause direct mitochondrial toxicity [46–48]. Utilization of newer ARV agents has decreased the prevalence of severe lipoatrophy, but lipohypertrophy and the underlying metabolic abnormalities persist. The DHHS “preferred” nucleoside analogues, tenofovir and abacavir, do not induce mitochondrial toxicity and have more favorable metabolic profiles [49,50]. In ACTG Study 5142, thymidine-sparing regimens were found to cause less lipoatrophy [51]. In addition, darunavir and atazanavir, the preferred and alternative PIs and the integrase strand transfer inhibitor have limited or modest impact on insulin sensitivity [20,52,53]. This has led to a recent decline in the incidence of type 2 DM in HIV-infected patients.

Statins can also increase insulin resistance and DM [54], although studies have shown mixed results [55–57]. The benefits of statin therapy likely outweigh the risk of DM since there is a significant cardiovascular event reduction with their use [58,59].

How is diabetes diagnosed in HIV-infected patients?

Optimal diabetes screening guidelines have not been established specifically for HIV-infected patients. The American Diabetes Association (ADA) guidelines recommend that diabetes in the general population be diagnosed by 2 elevated fasting blood glucose levels, HbA1c, oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), or high random glucose with classic symptoms of hyperglycemia [60]. Repeat testing is recommended every 3 years. The OGTT is recommended for diagnosis in pregnant women.

HbA1c may underestimate glycemic burden in HIV-infected individual due to higher mean corpuscular volume, NRTI use (specifically abacavir), or lower CD4 count [61–65]. The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) 2013 primary care guidelines for HIV-infected patients recommends obtaining a fasting glucose and/or HbA1c prior to and within 1–3 months after starting ARV [12]. Use of HbA1c threshold cutoff of 5.8% for the diagnosis of DM and testing every 6–12 months are recommended.

How should this patient’s diabetes be managed?

The ADA guidelines suggest a patient-centered approach to management of diabetes [66]. All patients should be educated about lifestyle modifications with medical nutrition therapy and moderate-intensity aerobic activity and weight loss [67]. If a patient is on lopinavir/ritonavir or a thymidine analogue (zidovudine, stavudine), one should consider switching the ARV regimen [2].

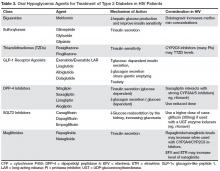

There are currently no randomized controlled trials of diabetes treatment specific to patients with HIV infection. Metformin is the first-line agent. It improves insulin sensitivity by reducing hepatic glucose production and improving peripheral glucose uptake and lipid parameters [68,69]. Other oral hypoglycemic agents used in the treatment of type 2 diabetes are shown in Table 3.

Case 2 Continued

The patient is switched to TAF/FTC plus dolutegravir with improvement in blood sugars. She is also started on metformin. Co-administration of metformin and dolutegravir will be carefully monitored since dolutegravir increases metformin concentration [70]. When dolutegravir is used with metformin, the total daily dose of metformin should be limited to 1000 mg.

• How should this patient be followed?

If the patient is still not at goal HbAb1c at follow-up, there are multiple other treatment options, including use of insulin. Goal HbA1c for most patients with type 2 DM is < 7%; however, this goal should be individualized for each patient in accordance with the ADA guidelines [12]. A longitudinal cohort study of 11,346 veterans with type 2 diabetes compared the glycemic effectiveness of oral diabetic medications ( metformin, sulfonylurea and a thiazolidinedione) among veterans with and without HIV infection. This study did not find any significant difference in HbA1c based on different diabetes medications. However the HBA1c reduction was less in black and Hispanic patients. The mechanism for the poorer response among these patients need to be evaluated further [71]. In addition to management of blood sugar, other CVD risk factors, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, smoking, etc, should be assessed and managed aggressively.