Impact of an Educational Training Program on Restorative Care Practice of Nursing Assistants Working with Hospitalized Older Patients

Abstract

- Background: Acute and prolonged exposure to hospital medical care can cause hospital-associated deconditioning with deleterious effects on patient care provision and quality of life. Physical rehabilitation provided by allied healthcare professionals can enable reacquisition of function via professional input into attainment of set goals. Separate to rehabilitative efforts, restorative care optimizes independence by motivating individuals to maintain and restore function. Nursing assistants (NAs) provide a significant amount of direct patient care and are well placed to deliver restorative care.

- Objective: To increase proportional restorative care interactions with hospitalized older adults by training NAs.

- Methods: A prospective cohort quality improvement (QI) project was undertaken at 3 acute hospital wards (patient minimum age 65 years) and 2 community subacute care wards in the UK. NAs working within the target settings received a 2-part restorative care training package. The primary evaluation tool was 51 hours in total of observation measuring the proportional change in restorative care events delivered by NAs.

- Results: NA-led restorative care events increased from 40 (pre-intervention) to 94 (post-intervention), representing a statistically significant proportional increase from 74% to 92% (χ2(1) 9.53, P = 0.002). NAs on occasions inadvertently emphasized restriction of function to manage risk and oblige with rest periods.

- Conclusion: Investing in NAs can influence the amount of restorative care delivered to hospitalized older adults at risk of hospital-associated deconditioning. Continued investment in NAs is indicated to influence top-down, mandated restorative care practice in this patient group.

Key words: older people; restorative care; hospital associated deconditioning; nursing assistants; rehabilitation; training.

Hospital-associated deconditioning is defined as a significant decline in functional abilities developed through acute and prolonged exposure to a medical care facility environment, and is independent of that attributed to primary pathologies resulting in acute admission [1]. Considerable research on iatrogenic complications in older hospitalized populations [1–5] has shown the impacts of hospital-associated deconditioning and associated dysfunctions on quality of life for patients and the resultant burden on health and social care provision [6].

Physical rehabilitation has been shown to restore function through high-dose repetition of task-specific activity [7], and the benefits attributed to extra physical therapy include improved mobility, activity, and participation [8]. Simply defined, physical rehabilitation is the reacquisition of function through multidisciplinary assessment and professional therapeutic input in attainment of set goals. A more recent nomenclature in health settings is “restorative care,” defined as a philosophy of care that encourages, enables, and motivates individuals to maintain and restore function, thereby optimizing independence [9]. It has been clearly defined as a philosophy separate from that of rehabilitation [9] and remote from task-related or “custodial care,” which is designed to assist in meeting patients’ daily activity needs without any therapeutic value.

,In UK rehabilitation wards, nursing staff provide 4.5 times as much direct patient care time compared with allied health professionals, with paraprofessional nursing assistants (NAs, equivalent to certified nurse assistants [CNAs] in the United States) responsible for half of this direct nursing care [10]. Kessler’s group examined the evolving role of NAs in UK hospitals [11]. From a national survey of 700 NAs and 600 trained nurses, the authors upheld the view that NAs act as direct caregivers including through routine tasks traditionally delivered by nurses. They identified that NAs exhibit distinct qualities, which are valued by qualified nurses, including routine task fulfilment and abilities relating to patients, which enable NAs to enhance care quality. Indeed, the national findings of Kessler’s group were generalizable to our own clinical setting where a NA cohort was a well-placed, available, and motivated resource to deliver therapeutically focused care for our hospitalized older population.

The theoretical relationship between care approaches is complex and represents a challenge for service users and policy makers. For instance, comprehensive rehabilitation delivery during an acute care episode may lead to users not seeking custodial care at home. Conversely, day-to-day activities realized by custodial care at home may lead to users not seeking acute rehabilitative care [12]. With stable resources being assigned to more dependent users in higher numbers, reactive care regardless of environment has often been the model of choice.

However, an economic rationale has developed more recently where investment in maintenance and preventative models results in healthcare savings with models including the 4Rs; reablement, reactivation, rehabilitation, and restorative care [13]. In North America, restorative care approaches have resulted in favorable results in nursing home facilities [14] and at home [15], and restorative care education and motivation training for nursing assistants was effective in supporting a change in beliefs and practice behaviors [16]. While results show restorative care practices in the non-acute care sector are advantageous, it is unknown whether these approaches if adopted in hospital settings affect subsequent healthcare utilization in the non-acute facilities, or even if they are feasible to implement in acute facilities by a staff group able to do so. Therefore, the purpose of this QI project was to deploy a restorative care educational intervention for NA staff working with hospitalized older adults with the aim of increasing the proportion of restorative care delivered.

Methods

Context

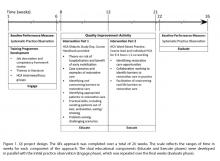

This project was conducted at a UK National Health Service university teaching hospital trust at 3 acute hospital wards (patient minimum age 65 years) and 2 community subacute care wards for older patients. Participants consisted of all permanent or long-term temporary (> 3 months continuous employment) NAs working in the target settings (n = 36). The QI project design is summarized in Figure 1. The project applied the 4Es translational approach to regulate the QI intervention: Engage, Educate, Execute, and Evaluate [17]. The reporting of this study follows SQUIRE guidance [18].

Intervention

The QI activity was a holistic educational process for all NA participants.

Didactic Study Day

Each NA attended a study day led by a physical therapist (up to 10 NAs per group). A student-centered training approach was adopted, recognizing variations in adult learning styles [19], and included seminar style theory, video case scenarios, group work, practical skills, open discussion, and reflection. The training package outline was compiled following consensus among the multi-disciplinary team working in the target settings and the steering group. Topics covered were theory on the risk of hospitalization and benefits of early mobilization; case scenarios and examples of restorative care; identifying and overcoming barriers to restorative care; identifying appro-priate patients for a restorative care approach; practical skills, including assisting patients out of bed, ambulation, and eating/drinking; and challenging, problem-solving scenarios. All participants received a course handbook to facilitate learning.

Ward-Based Practice

Measures

Type of Care Event

The quantity and nature of all NA-patient functional task-related care events was established by independent systematic observation pre- and post-intervention. Observers rated the type of care for observed patients as either custodial or restorative events using a tool described below. In addition, the numbers of patients receiving no restorative care events at all during observation was calculated to capture changes in rates between patients observed. The observational tool used was adapted from that utilized in a North American study of a long-term care facility [20], which demonstrated favorable intra-rater reliability (person separation reliability of 0.77), inter-rater reliability (80% to 100% agreement on each of the care behaviors), and validity (evidence of unidimensionality and good fit of the items). Adaptations accommodated for data collection in a hospital environment and alteration to UK nomenclature.

Three blinded volunteer assessors undertook observations. The observers monitored for activity in any 1 of 8 functional domains: bed mobility, transfers, mobility, washing and dressing, exercise, hygiene (mouth care/shaving/hair/nail care), toileting, and eating. Patient activity observed within these domains was identified as either a restorative or custodial care event. For example: “asks or encourages patient to walk/independently propel wheelchair to bathroom/toilet/day room/activities and gives them time to perform activity” was identified as a restorative care event, while “utilizes wheelchair instead of encourages ambulation and does not encourage patient to self-propel” was considered a custodial care event. All observations were carried out by student physical therapists in training or physical therapy assistants, all of whom were familiar in working in the acute facility with hospitalized older people. In an attempt to optimize internal consistency, observer skill was quality-controlled by ensuring observers were trained and their competency assessed in the use of the evaluation measurement tool.

Bays of 3 to 6 beds comprised each observation space. Three 90-minute time epochs were selected for observation—awakening (early morning), lunchtime (middle of the day), and afternoon (before evening meal)—with the aim that each time frame be observed on a minimum of 1 occasion on each of the 5 wards to generate a minimum of 15 observation sessions. Resources dictated observational periods to be 90-minutes maximum, per epoch, on weekdays only. The mean (range) time between the didactic study day and the ward-based practice day was 4 (1–8) weeks, and between the ward-based practice day and the second observational period was 6 (1–14) weeks.