A Longitudinal Study of Transfusion Utilization in Hospitalized Veterans

Discussion

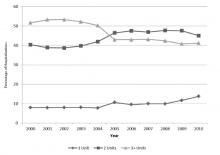

We also observed secular trends in the volume of RBCs administered. There was an increase in the percentage of hospitalizations in which 1 or 2 RBC units were used and a decline in transfusion of 3 or more units. The reduction in the use of 3 or more RBC units may reflect the adoption and integration of recommendations in patient blood management by clinicians,

which encourage assessment of the patients’ symptoms in determining whether additional units are necessary [7]. Such guidelines also endorse the avoidance of routine

administration of 2 units of RBCs if 1 unit is sufficient [8]. We have previously shown that, after coronary artery bypass grafting, 2 RBC units doubled the risk of pneumonia [9]; additional analyses indicated that 1 or 2 units of RBCs were associated with increased postoperative morbidity [10]. In addition, our previous research indicated that the probability of infection increased considerably between 1 and 2 RBC units, with a more gradual increase beyond 2 units [11]. With this evidence in mind, some studies at single sites have reported that there was a dramatic decline from 2 RBC units before initiation of patient blood management programs to 1 unit after the programs were implemented [12,13].

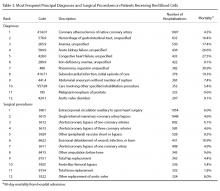

Medical patients who received a transfusion were often admitted for reason of anemia, cancer, organ failure, or pneumonia. Some researchers are now reporting that blood use, at certain sites, is becoming more common in medical rather than surgical patients, which may be due to an expansion of patient blood management procedures in surgery [16]. There are a substantial number of patient blood management programs among surgical specialties and their adoption has expanded [17]. Although there are fewer patient blood management programs in the nonsurgical setting, some have been targeted to internal medicine physicians and specifically, to hospitalists [1,18]. For example, a toolkit from the Society of Hospital Medicine centers on anemia management and includes anemia assessment, treatment, evaluation of RBC transfusion risk, blood conservation, optimization of coagulation, and patient-centered decision-making [19]. Additionally, bundling of patient blood management strategies has been launched to help encourage a wider adoption of such programs [20].

While guidelines regarding use of RBCs are becoming increasingly recognized, recommendations for the use of platelets and plasma are hampered by the paucity of evidence from randomized controlled trials [21,22]. There is moderate-quality evidence for the use of platelets with therapy-induced hypoproliferative thrombocytopenia in hospitalized patients [21], but low quality evidence for other uses. Moreover, a recent review of plasma transfusion in bleeding patients found no randomized controlled trials on plasma use in hospitalized patients, although several trials were currently underway [22].

Our findings need to be considered in the context of the following limitations. The data were from 3 VA hospitals, so the results may not reflect patterns of usage at other hospitals. However, AABB reports that there has been a general decrease in transfusion of allogeneic whole blood and RBC units since 2008 at the AABB-affiliated sites in the United States [2]; this is similar to the pattern that we observed in surgical patients. In addition, we report an overall view of trends without having details regarding which specific factors influenced changes in transfusion during this 11-year period. It is possible that the severity of hospitalized patients may have changed with time which could have influenced decisions regarding the need for transfusion.

In conclusion, the use of blood products decreased in surgical patients since 2002 but remained the same in medical patients in this VA population. Transfusions increased over time for patients who were admitted to the hospital for reason of infection, but decreased since 2002 for those admitted for cardiovascular disease or cancer. The number of RBC units per hospitalization decreased over time. Additional surveillance is needed to determine whether recent evidence regarding blood management has been incorporated into clinical practice for medical patients, as we strive to deliver optimal care to our veterans.

Corresponding author: Mary A.M. Rogers, PhD, MS, Dept. of Internal Medicine, Univ. of Michigan, 016-422W NCRC, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-2800, maryroge@umich.edu.

Funding/support: Department of Veterans Affairs, Clinical Sciences Research & Development Service Merit Review Award (EPID-011-11S). The contents do not represent the views of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs or the U.S. Government.

Financial disclosures: None.

Author contributions: conception and design, MAMR, SS; analysis and interpretation of data, MAMR, JDB, DR, LK, SS; drafting of article, MAMR; critical revision of the article, MAMR, MTG, DR, LK, SS, VC; statistical expertise, MAMR, DR; obtaining of funding, MTG, SS, VC; administrative or technical support, MTG, LK, SS, VC; collection and assembly of data, JDB, LK.