The Value of Routine Transthoracic Echocardiography in Defining the Source of Stroke in a Community Hospital

Methods

Setting

All data was collected from the echocardiography lab at Anne Arundel Medical Center, a 384-bed community hospital in Annapolis, MD. The medical center sees about 250 patients a day in its emergency department and admits about 30,000 patients annually. All echocardiograms are performed by a centralized laboratory accredited by the Intersocietal Commission for the Accreditation of Echocardiography Laboratories, which performs approximately 6000 echocardiograms annually.

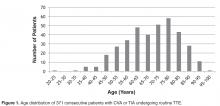

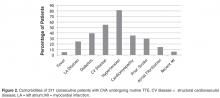

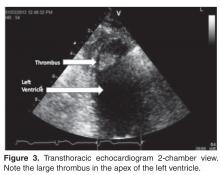

All TTEs done for the diagnosis of CVA or TIA between 1 February 2013 and 1 May 2013 were evaluated in consecutive fashion by report review. Reports were searched for any cardiac source of embolism to include thrombus, tumor, vegetation, shunt, aortic atheroma, or any other finding that was felt to be a clear source of embolism by the interpreting cardiologist. We did not include entities such as mitral valve prolapse, patent foramen ovale, and isolated atrial septal aneurysms since their association with CVA/TIA has been questioned. Also not included was cardiomyopathy without aneurysm, apical wall motion abnormality, or intra-cavitary thrombus solely because the ejection fraction was less than 35%, as the literature does not support these conditions as clear causes of TIA or CVA.

In addition to reviewing echocardiogram reports, all patient records were evaluated for clinical variables including age, gender, presence of atrial fibrillation, hypertension, diabetes, past CVA, left atrial dilation by calculation of indexed direct left atrial volume, recent myocardial infarction, and known cardiovascular disease.

All echocardiograms were performed on Hewlet-Packard Vivid 7 or Vivid 9 (GE Healthcare, Wauwatosa, WI) by technicians who held registered diagnostic cardiac sonographer status. All TTEs contained the “standard” views in accordance with published guidelines [10].Saline contrast to look for shunts was not standard on these studies. Echocardiogram images were stored digitally and read from an EchoPac (GE Healthcare, Wauwatosa, WI) reading station. All echocardiograms were interpreted by one of 16 American Board of Internal Medicine–certified cardiologists, 5 of whom were testamurs (physicians who have passed one of the examinations of special competence in echocardiography). These 5 interpreted 20% of the studies.

Results

Discussion

Our data are in keeping with those of others, though our yield was even lower than that reported in previous studies [1–3]. The low yield may be explained by a number of factors. First, we did not include patent foramen ovale or atrial septal aneurysms (which account for a high percentage of embolic sources in other publications) since there is not a clear consensus that any of those entities are associated with an increased risk of embolic events. The exclusion of cardiomyopathy as a cause of CVA or TIA is arguable, but its link to CVA or TIA is also unproven. One study did associate cardiomyopathy with CVA [12]; however, the mechanism is not clear, as the incidence of CVA in cardiomyopathy has been described as similar regardless of the severity of left ventricular dysfunction [13].Many past reports have come from tertiary care centers, where there may be referral bias whereas our data come from consecutive patients at a single community hospital.

TTE is relatively quick to perform and interpret and carries no physical risk to a patient. However, our data suggest that ordering TTE routinely in the setting of CVA offers little value. With health care organizations turning their attention to reducing low-value care, which potentially wastes limited resources, considerations of value and effectiveness continue to be a priority. Our findings suggest TTE use in this setting conflicts with the current trajectory of value-based medical practice. As well, a prior Markov model decision analysis found that TTE is not cost-effective when used routinely to identify source of emboli in stroke [14].

Despite the low yield of TTE in evaluating for a cardiac source of CVA, TTEs continue to be frequently ordered. In our own institution, 48% of patients with a CVA or TIA underwent a TTE based on preferences and habits of individual admitting physicians and without any structured criteria. Order sets for CVA admissions do not include this test; physicians are adding it but not for any particular patient characteristic or exam finding.

There are a number of reasons that echocardiograms may be ordered more frequently by some. A documented decline in ordering echocardiograms was seen following education at one center [15], suggesting that lack of knowledge about the limitations of TTE may be a factor. A second potential factor is fear of medicolegal consequences. Indeed, the current American Heart Association/American Stroke Association guidelines for the early management of adults with ischemic stroke [16] offers no formal recommendations or clear indications.

Computerized decision support (CDS) that links the medical record to appropriateness criteria could potentially reduce the inappropriate use of TTE. CDS has been shown to be effective in reducing unnecessary ordering of tests in other settings [17–19].

Among the limitations in our analysis is the heterogeneity in echocardiogram readers. However, this heterogeneity may makes the study more relevant as it reflects the reality in most community hospitals. Another potential limitation is that saline contrast studies were not used routinely; however, this too is typical at community hospitals. Also, while all echocardiograms were interpreted by “board-certified” cardiologists, only 5 had passed the “examination of special competence” to be certified as a testamur of the National Board of Echocardiography, raising the question as to whether subtle findings could have been missed. However, there were no relevant findings in the 20% of studies interpreted by the testamurs, suggesting that the other echocardiographers were not missing diagnoses. Finally, we had only 10 patients younger than age 45 and so the study conclusions are less definitive for that age-group.

Conclusion

TTE was of limited utility in uncovering a cardiac source of embolism in a typical population with CVA or TIA.Based upon the data, we believe that TTE should not be used routinely in the setting of CVA; however, we do recognize that TTE may be of value in patients who have other comorbidities that would place them at increased risk of embolic CVA such as a recent anterior MI, those at risk for endocarditis, or those with brain imaging findings suggestive of embolic CVA [20]. Ordering a low-value test such as a TTE in the setting of TIA or CVA adds cost and does not often yield a clinically meaningful results. In addition, a “negative” TTE can be misinterpreted as a normal heart and forestall additional workup such as transesophageal echocardiography and long-term rhythm analysis, which may be of higher value. We suggest that in a community hospital setting the determination of need for TTE be made based on the clinical nuances of the case rather than by habit or as part of standardized order sets.

Corresponding author: Barry Meisenberg, MD, DeCesaris Cancer Institute, 2001 Medical Parkway, Annapolis, MD 21146, meisenberg@aahs.org.

Financial disclosures: None.

Author contributions: conception and design, BM, WCM; analysis and interpretation of data, BM, WCM; drafting of article, RHB, BM, WCM; critical revision of the article, BM, WCM; administrative or technical support, JC; collection and assembly of data, RHB, JC.