Case 1

A 73-year-old woman with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus reports poor sleep quality with frequent awakenings during the night and excessive daytime sleepiness. She states that she can fall asleep within 5 minutes, but often is awoken throughout the night with a sensation of breathlessness. She has snored for many years, but the nursing staff at her NH facility has recently commented that her snoring has gone from intermittent to constant. She cannot remember the last time she has had restful sleep. She consumes 3 to 4 cups of caffeinated beverages daily to counter her sleepiness. She denies smoking or illicit drug or alcohol use. Her review of systems was notable for a 30-lb weight gain over the last year, and she reports increasing fatigue, irritability, and memory and concentration issues. Her current medication list includes metformin and amlodipine. Her examination is remarkable for a BMI of 31, large neck circumference (> 16), tonsillar enlargement, a crowded oropharynx, micrognathia, lungs clear to auscultation bilaterally, heart sounds of normal S1 and S2, and legs with trace pitting edema.

Case 1 Reflection: Sleep-Disordered Breathing

Sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) encompasses 3 distinct syndromes involving abnormal respiratory patterns during sleep: obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), central sleep apnea, and sleep hypoventilation syndrome. OSA, the most common type of SDB, typically involves symptoms of loud snoring, choking, or gasping during sleep that often results in recurrent awakenings from sleep; a sense of unrefreshing sleep and subsequent daytime sleepiness, fatigue and impaired concentration. The breathing disturbances observed in OSA include hypopnea (slow or shallow breathing) and/or apnea (lack of breathing). The complete OSA diagnostic criteria are listed in Table 1. To definitively diagnose OSA, an overnight sleep study must be performed demonstrating 5 or more obstructive apneas/hypopneas per hour (each lasting at least 10 seconds) during sleep [13]. OSA can be further classified into degree of severity (mild, moderate, severe) based on the number of apnea/hypopnea episodes per hour [14]. Significant OSA is most often treated with a continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) device that applies consistent pressure to maintain an open airway in the patient.

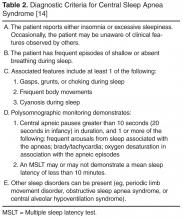

Unlike OSA, which demonstrates reduction in airflow despite demonstration of respiratory effort, central sleep apnea (CSA) represents the significant reduction or absence of both respiratory effort (lack of a central message to breathe) and respiratory airflow during sleep. In Cheyne-Stokes CSA, a serious cardiac or neurological condition is often present, leading to cyclical crescendo and decrescendo changes in breathing amplitude along with 5 or more episodes of apnea per hour. Sleep hypo-ventilation syndrome, also known as obesity hypoventilation syndrome, characteristically demonstrates a rise in PaCO2 greater than 10 mm Hg during sleep or PaO2 desaturations unexplained by apneic episodes; the resulting hypoxemia frequently leading to an increased risk of erythrocytosis, pulmonary hypertension, corpulmonale or respiratory failure (Table 2). Treatment-emergent central apnea (previously known as complex or mixed sleep apnea) is found in patients who have a predominantly obstructive apnea during polysomnography; however, when CPAP is applied a central apnea pattern appears [15]. In these cases, a cause for central apnea is usually not apparent. The management of treatment-emergent central apnea includes management of underlying diseases contributing to OSA or CSA and also requires careful titration of noninvasive ventilation with lower pressures.

Although previous studies have observed high rates (60%–90%) of SDB in NH settings [16,17], one study observed that only 0.5% of nursing home residents carried a diagnosis with SDB, suggesting that SDB is being grossly underappreciated amongst NH residents over the age of 65 [18]. In order to evaluate for SBD, routine annual physical exams or medical chart reviews can elicit the risk factors for sleep apnea (eg, obesity [per BMI], male sex, postmenopausal women, family history of sleep apnea) as well as common comorbidities (eg, hypertension, coronary artery disease, and diabetes). Formal evaluation consists of a sleep evaluation with a sleep specialist and polysomnography (PSG; sleep study) that can be performed in the sleep center or at home depending on the patient’s history and other medical issues.

Case 1 Outcome

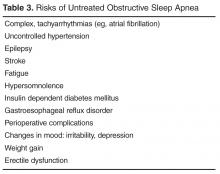

The patient has a form of sleep-disordered breathing that is causing functional impairment of her daily activities. She underwent PSG, which demonstrated severe OSA with 46 respiratory events an hour during sleep (normal, < 5). Her sleep apnea, if untreated, would put her at risk for cognitive decline, uncontrolled hypertension, stroke, weight gain, gastroesophageal reflux disease, changes in mood with increasing irritability, fatigue and sleepiness, and death (Table 3) [19,20]. Based on her sleep apnea severity, CPAP use while sleeping was prescribed. She was initially reluctant to use the prescribed CPAP because of claustrophobia due to the size of the mask and discomfort with the pressure of the airflow. With education about sleep apnea, optimization of the mask for comfort and for prevention of air leak, and heated humidification to her machine, she was able to tolerate CPAP at least 5 hours per night. At her 3-month visit after initiating CPAP therapy, she reported good CPAP tolerability, less daytime sleepiness, and improved quality of life [21].