Applying a Quality Improvement Framework to Operating Room Efficiency in an Academic-Practice Partnership

Methods

Setting

The OR at UHCMC contains 4 operating suites that serve over 25,000 patients per year and train over 900 residents each year. Nearly 250 surgeons in 23 departments use the OR. The OR schedule at our institution is coordinated by block scheduling, as described above. If a surgical department cannot fill the block, they must release the time to central scheduling for re-allocation of the time to another department.

Application of QI Process

This QI project was an academic-practice collaboration between UHCMC and a graduate level course at Case Western Reserve University called The Continual Improvement of Healthcare: an Interdisciplinary Course [4]. Faculty course instructors solicit applications of QI projects from departments at UHCMC. The project team consisted of 4 students (from medicine, social work, public health, and bioethics), 2 administrative staff from UHCMC, and a QI coach who is on the faculty at Case Western. Guidance was provided by 2 faculty facilitators. The students attended 15 weekly class sessions, 4 meetings with the project team, numerous data gathering sessions with other hospital staff, and held a handful of outside-class student team meetings. An early class session was devoted to team skills and the Seven-Step meeting process [5]. Each classroom session consisted of structured group activities to practice the tools of the QI process.

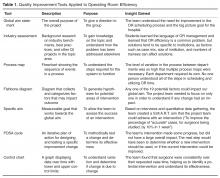

Tool 1: Global Aim

The team first established a global aim: to improve the OR block utilization rate at UHCMC. This aim was based on the initial project proposal from UHCMC. The global aim explains the reason that the project team was established, and frames all future work [7].

Tool 2: Industry Assessment

Based on the global aim, the student team performed an industry assessment in order to understand strategies for improving block utilization rate in use at other institutions. Peer-reviewed journal articles and case reports were reviewed and the student team was able to contact a team at another institution working on similar issues.

Overall, 2 broad categories of interventions to improve block utilization were identified. Some institutions addressed the way time in the OR was scheduled. They made improvements to how block time was allotted, timing of cases, and dealing with add-on cases [8]. Others focused on using time in the OR more efficiently by addressing room turnover, delays including waiting for surgeons, and waiting for hospital beds [9]. Because the specific case mix of each hospital is so distinct, hospitals that successfully made changes all used a variety of interventions [10–12]. After the industry assessment, the student team realized that there would be a large number of possible approaches to the problem of block utilization, and a better understanding of the actual process of scheduling at UHCMC was necessary to find an area of focus.

Tool 3: Process Map

As the project team began to address the global aim of improving OR block utilization at UHCMC, they needed to have a thorough understanding of how OR time was allotted and used. To do this, the student team created a process map by interviewing process stakeholders, including the OR managers and department schedulers in orthopedics, general surgery, and urology, as suggested by the OR managers. The perspective of these staff were critical to understanding the process of operating room scheduling.

Through the creation of the process map, the project team found that there was wide variation in the process and structure for scheduling surgeries. Some departments used one central scheduler while others used individual secretaries for each surgeon. Some surgeons maintained control over changing their schedule, while others did not. Further, the project team learned that the metric of block utilization rate was of varying importance to people working on the ground.

Tool 4: Fishbone Diagram

After understanding the process, the project team considered all of the factors that

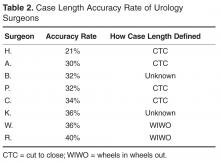

Tool 5: Specific Aim

Though the global aim was to improve block utilization, the project team needed to chose a specific aim that met S.M.A.R.T criteria: Specific, Measureable, Achievable, Results-focused, and Time-bound [7]. After considering multiple potential areas of initial focus, the OR staff suggested focusing on the issue of case length accuracy. In qualitative interviews, the student team had found that the surgery request forms ask for “case length,” and the schedulers were not sure how the surgeons defined it. When the OR is booked for an operation, the amount of time blocked out is the time from when the patient is brought into the operating room to the time that the patient leaves the room, or WIWO (Wheels In Wheels Out). This WIWO time includes anesthesia induction and preparations for surgery such as positioning. Some surgeons think about case length as only the time that the patient is operated on, or CTC (Cut to Close). Thus, the surgeon may be requesting less time than is really necessary for the case if he or she is only thinking about CTC time. The student team created a survey and found that 2 urology surgeons considered case length to be WIWO, and 4 considered case length to mean CTC.