Current Therapeutic Approaches to Renal Cell Carcinoma

Case Study

Initial Presentation

A 74-year-old man who works as an airplane mechanic repairman presents to the emergency department with sudden worsening of chronic right upper arm and shoulder pain after lifting a jug of orange juice. He does not have a significant past medical history and initially thought that his pain was due to a work-related injury. Upon initial evaluation in the emergency department he is found to have a fracture of his right humerus. Given that the fracture appears to be pathologic, further workup is recommended.

• What are common clinical presentations of RCC?

Most patients are asymptomatic until the disease becomes advanced. The classic triad of flank pain, hematuria, and palpable abdominal mass is seen in approximately 10% of patients with RCC, partly because of earlier detection of renal masses by imaging performed for other purposes [10]. Less frequently, patients present with signs or symptoms of metastatic disease such as bone pain or fracture (as seen in the case patient), painful adenopathy, and pulmonary symptoms related to mediastinal masses. Fever, weight loss, anemia, and/or varicocele often occur in young patients (≤ 46 years) and may indicate the presence of a hereditary form of the disease. Patients may present with paraneoplastic syndromes seen as abnormalities on routine blood work. These can include polycythemia or elevated liver function tests (LFTs) without the presence of liver metastases (known as Stauffer syndrome), which can be seen in localized renal tumors. Nearly half (45%) of patients present with localized disease, 25% present with locally advanced disease, and 30% present with metastatic disease [11]. Bone is the second most common site of distant metastatic spread (following lung) in patients with advanced RCC.

• What is the approach to initial evaluation for a patient with suspected RCC?

Initial evaluation consists of a physical exam, laboratory tests including complete blood count (CBC) and comprehensive metabolic panel (calcium, serum creatinine, LFTs, lactate dehydrogenase [LDH], and urinalysis), and imaging. Imaging studies include computed tomography (CT) scan with contrast of the abdomen and pelvis or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the abdomen and chest imaging. A chest radiograph may be obtained, although a chest CT is more sensitive for the presence of pulmonary metastases. MRI can be used in patients with renal dysfunction to evaluate the renal vein and inferior vena cava (IVC) for thrombus or to determine the presence of local invasion [12]. Although bone and brain are common sites for metastases, routine imaging is not indicated unless the patient is symptomatic. The value of positron emission tomography in RCC remains undetermined at this time.

• What are the therapeutic options for limited-stage disease?

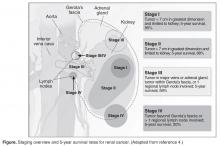

For patients with nondistant metastases, or limited-stage disease, surgical intervention with curative intent is considered. Convention suggests considering definitive surgery for patients with stage I and II disease, select patients with stage III disease with pathologically enlarged retroperitoneal lymph nodes, patients with IVC and/or cardiac atrium involvement of tumor thrombus, and patients with direct extension of the renal tumor into the ipsilateral adrenal gland if there is no evidence of distant disease. While there may be a role for aggressive surgical intervention in patients with distant metastatic disease, this topic will not be covered in this review.

Surgical Intervention

Once patients are determined to be appropriate candidates for surgical removal of a renal tumor, the urologist will perform either a radical nephrectomy or a nephron-sparing nephrectomy, also called a partial nephrectomy. The urologist will evaluate the patient based on his or her body habitus, the location of the tumor, whether multiple tumors in one kidney or bilateral tumors are present, whether the patient has a solitary kidney or otherwise impaired kidney function, and whether the patient has a history of a hereditary syndrome involving kidney cancer as this affects the risk of future kidney tumors.

A radical nephrectomy is surgically preferred in the presence of the following factors: tumor larger than 7 cm in diameter, a more centrally located tumor, suspicion of lymph node involvement, tumor involvement with renal vein or IVC, and/or direct extension of the tumor into the ipsilateral adrenal gland. Nephrectomy involves ligation of the vascular supply (renal artery and vein) followed by removal of the kidney and surrounding Gerota’s fascia. The ipsilateral adrenal gland is removed if there is a high-risk for or presence of invasion of the adrenal gland. Removal of the adrenal gland is not standard since the literature demonstrates there is less than a 10% chance of solitary, ipsilateral adrenal gland involvement of tumor at the time of nephrectomy in the absence of high-risk features, and a recent systematic review suggests that the chance may be as low as 1.8% [14]. Preoperative factors that correlated with adrenal involvement included upper pole kidney location, renal vein thrombosis, higher T stage (T3a and greater), multifocal tumors, and evidence for distant metastases or lymph node involvement. Lymphadenectomy previously had been included in radical nephrectomy but now is performed selectively. Radical nephrectomy may be performed as either an open or laparoscopic procedure, the latter of which may be performed robotically [15]. Oncologic outcomes appear to be comparable between the 2 approaches, with equivalent 5-year cancer-specific survival (91% with laparoscopic versus 93% with open approach) and recurrence-free survival (91% with laparoscopic versus 93% with open approach) [16]. The approach ultimately is selected based on provider- and patient-specific input, though in all cases the goal is to remove the specimen intact [16,17].

Conversely, a nephron-sparing approach is preferred for tumors less than 7 cm in diameter, for patients with a solitary kidney or impaired renal function, for patients with multiple small ipsilateral tumors or with bilateral tumors, or for radical nephrectomy candidates with comorbidities for whom a limited intervention is deemed to be a lower-risk procedure. A nephron-sparing procedure may also be performed open or laparoscopically. In nephron-sparing procedures, the tumor is removed along with a small margin of normal parenchyma [15].

In summary, the goal of surgical intervention is curative intent with removal of the tumor while maintaining as much residual renal function as possible to limit long-term morbidity of chronic kidney disease and associated cardiovascular events [18]. Oncologic outcomes for radical nephrectomy and partial nephrectomy are similar. In one study, overall survival was slightly lower in the partial nephrectomy cohort, but only a small number of the deaths were due to RCC [19].

Adjuvant Therapy

Adjuvant systemic therapy currently has no role following nephrectomy for RCC because no systemic therapy has been able to reduce the likelihood of relapse. Randomized trials of cytokine therapy (eg, interferon, interleukin 2) or tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs; eg, sorafenib, sunitinib) with observation alone in patients with locally advanced completely resected RCC have shown no delay in time to relapse or improvement of survival with adjuvant therapy [20]. Similarly, adjuvant radiation therapy has not shown benefit even in patients with nodal involvement or incomplete resection [21]. Therefore, observation remains the standard of care after nephrectomy.

Renal Tumor Ablation

For patients who are deemed not to be surgical candidates due to age, comorbidities, or patient preference and who have tumors less than 4 cm in size (stage I tumors), ablative techniques may be considered. The 2 most well-studied and effective techniques at present are cryoablation and radiofrequency ablation (RFA). Microwave ablation may be an option in some facilities, but the data in RCC are limited. An emerging ablative technique under investigation is irreversible electroporation. At present, the long-term efficacy of all ablative techniques is unknown.

Patient selection is undertaken by urologists and interventional radiologists who evaluate the patient with ultrasound, CT, and/or MRI to determine the location and size of the tumor and the presence or absence of metastatic disease. A pretreatment biopsy is recommended to document the histology of the lesion to confirm a malignancy and to guide future treatment for recurrent or metastatic disease. Contraindications to the procedure include the presence of metastatic disease, a life expectancy of less than 1 year, general medical instability, or uncorrectable coagulopathy due to increased risk of bleeding complications. Tumors in close proximity to the renal hilum or collecting system are a contraindication to the procedure because of the risk for hemorrhage or damage to the collecting system. The location of the tumor in relation to the vasculature is also important to maximize efficacy because the vasculature acts as a “heat sink,” causing dissipation of the thermal energy. Occasionally, stenting of the proximal ureter due to upper tumor location is necessary to prevent thermal injury that could lead to urine leaks.

Selection of the modality to be used primarily depends on operator comfort, which translates to good patient outcomes, such as better cancer control and fewer complications. Cryoablation and RFA have both demonstrated good clinical efficacy and cancer control of 89% and 90%, respectively, with comparable complication rates [22]. There have been no studies performed directly comparing the modalities.