Cardiovascular Risk Reduction in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes

Case Continued

After the initial diagnosis, the patient was seen by a registered dietitian and followed a Mediterranean diet for some time but has since stopped. He is seen regularly for follow-up of his diabetes at 3- to 6-month intervals. He initially lost some weight but has unfortunately regained the weight. He tells you proudly that he finally quit smoking. He was started on metformin about 6 months after diagnosis to address his glycemic control. He continues on the metformin now as his only medication.

The patient returns to clinic for his usual follow-up visit approximately 5 years after initial diagnosis. He is feeling well with no new medical issues. He has no clinically apparent retinopathy or macrovascular complications. On examination, his blood pressure is 140/90 mm Hg and the remainder of the exam is unremarkable. His bloodwork shows an A1c of 8% and a low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) level of 124 mg/dL. His albumin-to-creatinine ratio is normal.

How often should cardiovascular risk be reassessed?

When should initiating pharmacotherapy to reduce risk in primary prevention be considered?

In the population with diabetes, statins and renin-angiotensin-aldosterone inhibition are the mainstays of pharmacotherapy for cardiovascular risk reduction. In the presence of clinical macrovascular disease, the standard of care includes both of these therapies. However, there is also a great deal of data that supports the use of these therapies for primary prevention.

Statins

Major studies on the benefits of statin therapy in people with diabetes have consistently shown decreased cardiovascular disease and mortality. The Heart Protection Study included a subgroup of patients with diabetes in which patients over the age of 40 were randomly assigned to simvastatin or placebo. Consistently across all subgroups, there was a relative risk reduction of 22% to 33% for the primary outcome of first cardiovascular event over 5 years. This effect was maintained even in those who did not have elevated LDL-C at randomization [46]. Similarly, the Collaborative Atorvastatin Diabetes Study (CARDS) randomized patients with T2DM, over age 40, with at least 1 other vascular risk factor to atorvastatin 10 mg or placebo. They found a 37% risk reduction in time to first event over 4 years with atorvastatin, with consistent results across all subgroups [47].

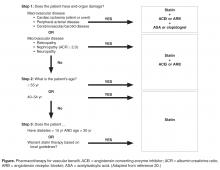

Based on these studies, it is recommended that all patients with diabetes be placed on statin therapy to reduce vascular risk at age 40 years (CDA, ADA, American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association [ACC/AHA]) [20,45,48]. If under age 40 years, statin therapy should be considered in the presence of other risk factors (ADA, ACC/AHA) [45,48], or if diabetes duration is more than 15 years and age is greater than 30 years, or there are micro- or macrovascular complications (CDA) [20].

Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone Inhibition

Similar to research into statin therapy, a considerable amount of research has been dedicated to renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) blockade for the primary purpose of vascular risk reduction, even in the absence of hypertension, in those with diabetes. In a prespecified substudy of the Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation (HOPE) trial, known as MICRO HOPE, patients with diabetes who were older than 55 years of age, with at least 1 other cardiovascular risk factor, were randomized to receive ramipril 10 mg daily or placebo. In this study, ramipril reduced the risk for myocardial infarction (22%), stroke (33%), cardiovascular death (37%), and all-cause mortality (24%) over 4.5 years [49]. In the Ongoing Telmisartan Alone and in Combination with Ramipril Global Endpoint Trial (ONTARGET), patients at high risk for cardiovascular disease were randomized to telmisartan 80 mg or ramipril 10 mg. In the diabetes subgroup, there were similar risk reductions and no statistical difference between the groups [50]. A 2012 meta-analysis assessed the benefits of RAAS blockade compared with placebo for primary prevention in high-risk individuals, or secondary prevention in those with established vascular disease. A reduction in cardiovascular death, all-cause mortality, fatal or nonfatal myocardial infarction, and stroke was seen across all subgroups, including those with and without diabetes or hypertension [51].

The CDA currently recommends that an ACE inhibitor or ARB be given to all patients with diabetes who are 55 years of age or older, or have macro- or microvascular disease, for the primary purpose of decreasing risk for vascular disease, even in the absence of hypertension. An agent and dose with proven vascular protective benefit should be chosen when selecting an ACE inhibitor or ARB [20].

Should this patient start ASA therapy?

Whether to start daily low-dose ASA for primary prevention of coronary artery disease has been a long-standing question in patients with diabetes. The benefits of ASA therapy with regards to coronary artery disease have long been known from a secondary prevention standpoint, and given the low risk and long experience, primary prevention seemed reasonable. However, no high-quality randomized controlled trials enrolling large numbers of patients with diabetes have been performed in the current era of medical therapy, specifically in the era of widespread statin use. The initial studies examining ASA use in primary prevention were analyzed in a meta-analysis in 1994 and showed a trend towards benefit for ASA in patients with diabetes [52]. Further trials increased the number of diabetes patient-years studied but did not change the initial result. Five meta-analyses have been conducted on the currently available trials, and all but one do not show a significant reduction in coronary artery disease or stroke in patients with diabetes [53–57]. In addition, ASA is known to cause a small absolute increase in the risk for gastrointestinal hemorrhage that is consistent across all studies, with a number needed to harm of approximately 100 over 2.5 years. Therefore, the possible small absolute benefit that was seen in ASA trials with regards to coronary artery disease in the era before statin therapy must be weighed against the known risk of bleeding. Because of this, the CDA and European Society of Cardiology have recommendations against the routine use of ASA for primary prevention in patients with diabetes [12,20].

A summary of pharmacotherapy for cardiovascular risk reduction is shown in the Figure.