Assessment and Treatment of Late-Life Depression

From the Department of Neuropsychiatry and Behavioral Sceince, University of South Carolina School of Medicine, Columbia, SC.

Abstract

- Objective: To review the identification, clinical assessment and treatment of patients with late-life depression.

- Methods: Review of the literature.

- Results: Depressive symptoms are present in up to 1 in 4 older adults. Comprehensive evaluation of depressive symptoms in this population often requires a multidisciplinary and collaborative approach between primary care, mental health, and other ancillary providers. Key aspects include a detailed history, physical and mental status examinations, cognitive and functional status assessment, and suicide risk assessment. Treatment options include anti-depressants, psychotherapy, and electroconvulsive therapy.

- Conclusion: A systematic approach to evaluating depressive symptoms in the elderly can enhance timely recognition and treatment.

Key words: Late-life depression; clinical assessment; antidepressants; psychotherapy; electroconvulsive therapy.

The U.S. population is aging, and with this comes the potential for increased health care needs. In 2014, there were over 46 million Americans age 65 and over (14.5% of the U.S. population). This number is projected to increase to 88 million by the year 2050 [1]. One in 4 older adults suffers with depressive symptoms that cause distress and functional impairment [2]. The World Health Organization Global Burden of Disease Study found depressive disorders to be the leading cause of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) and the second leading cause of years lived with disability (YLDs). The burden of disease due to depressive disorders increased by 37.5% between 1990 and 2010, and 10.4% was attributable to aging [3]. These figures underscore the importance of accurate assessment and treatment of depression in the elderly. In this article, we review the identification, clinical assessment, and treatment of patients with late-life depression.

Diagnostic Criteria

Prevalence

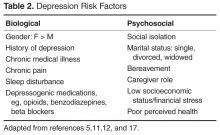

It is estimated that 1% to 4% of community-dwelling adults age 65 and older suffer from MDD, with women more likely to be affected than men (prevalence of 4.4% vs. 2.7) [2,5–7]. This estimate is low compared with lifetime prevalence of almost 20% in the general adult population [8]. However, when depressive symptoms that do not meet criteria for MDD are considered, prevalence rates increase up to 25% [2,9]. These estimates also vary by clinical setting, with the highest rates (up to 40%) among elderly patients in long-term care facilities [10,11]. While individuals with subsyndromal depression may experience fewer symptoms than those with MDD, clinically significant distress persists, impacting health and functional status. Depression is associated with overall poor social or occupational functioning, cognitive decline, increased health care utilization and cost, increased morbidity and mortality from medical illness, and increased suicide mortality [5,9,10,12].

Identifying LLD

Accurate identification of LLD also requires recognition of the differences in the presentation of LLD compared with onset in earlier life. Depression in younger adults is often marked by depressed mood and loss of interest [18]. In contrast, older adults may present with increased anger or irritability [5]. Younger adults are more likely to report suicidal thoughts while older patients report feelings of hopelessness and thoughts of death [18]. LLD is often characterized by increased somatic complaints, hypochondriasis, or pain [5,18,19]. Another major difference lies in the presentation of cognitive difficulties. Younger patients typically complain of poor concentration or indecisiveness. Geriatric patients may present with cognitive changes including objective findings of slower processing speed and executive dysfunction on neuropsychological testing [17].

Depression rating scales may aid in identification of LLD. They are not a substitute for clinical diagnosis but can be useful as screening tools. Two commonly utilized depression rating scales are the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) and the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). GDS is a 30-item instrument developed specifically for older adults. Shorter 15-item, 5-item, and 4-item versions exist. The scale utilizes a Yes/No format and can be self- or clinician-administered [20]. One advantage of the GDS lies in its focus on psychological and cognitive aspects of depression rather than neurovegetative symptoms that may overlap with medical illnesses common in older adults [21]. The PHQ-9 is a 9-item self- or clinician-administered screening tool designed for use in primary care settings and has also been validated in geriatric populations [22,23]. The 9 items on this scale correspond to the DSM-5 criteria for major depression. A shorter 2-item version (PHQ-2) has also been validated, and a positive screen on this test should prompt administration of the full-length version. Both versions have approximately 80% sensitivity and specificity in detecting depression. An added advantage of PHQ-9 over GDS is that it can be useful in monitoring treatment response over time [22,23]