A Talking Map for Family Meetings in the Intensive Care Unit

3. Ask the Family's Understanding of the Situation (Ask-Tell-Ask)

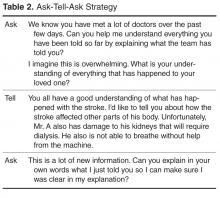

Asking the family to explain the situation in their own language reveals how well they understand the medical facts and helps the medical team determine what information will be most helpful to the family. An opening statement might be “We have all seen your dad and talked to many of his providers. It would help us all be on the same page if you can you tell me what the doctors are telling you?” Starting with the family’s understanding builds trust with the medical team as it creates an opportunity for the family to lead the meeting and indicates that the team is available to listen to their concerns. Asking surrogates for their understanding allows them to tell their story and not hear a reiteration of things they already know. Providing time for the family to share their perspective of the care elicits family’s concerns.

In a large meeting, ensure that all members of the family have an opportunity to communicate their concerns. Does a particular person do all of the talking? Are there individuals that do not speak at all? One way to further understand unspoken concerns during the meeting is to ask “I notice you have been quiet, what questions do you have that I can answer?” There may be several rounds of “asking” in order to ensure all the family members’ concerns are heard. Letting the family tell what they have heard helps the clinicians get a better idea of their health literacy. Do they explain information using technical data or jargon? Finally, as the family talks the clinicians can determine how surprising the “serious news” will be to them. For example, if the family says they know their dad is doing much worse and may die, the information to be delivered can be truncated. However if family incorrectly thinks their dad is doing better or is uncertain they will be much more surprised by the serious news.

After providing time for the family to express their understanding, tell them the information the team needs to communicate. When delivering serious news it is important to focus on the key 1 to 2 points you want the family to take away from the meeting. Typically when health care professionals talk to each other, they talk about every medical detail. Families find this amount of information overwhelming and are not sure what is most important, asking “So what does that mean?” Focusing on the “headline” helps the family focus on what you think the most important piece of information is. Studies suggest that what families most want to know is what the information means for the patient’s future and what treatments are possible. After delivering the new information, stop to allow the family space to think about what you said. If you are giving serious news, you will know they have heard what you said as they will get emotional (see next step).

Checking for understanding is the final “ask” in Ask-Tell-Ask. Begin by asking “What questions do you have?” Data in primary care has shown that patients are more likely to ask questions if you ask “what questions do you have” rather than “do you have any questions?” It is important to continue to ask this question until the family has asked all their questions. Often the family’s tough questions do not come until they get more comfortable and confident in the health care team. In cases where one family member is dominant it might also help to say “What questions do others have?” Next, using techniques like the “teach back” model the physician should check in to see what the family is taking away from the conversation. If a family understands, they can “teach back” the information accurately. This “ask” can be done in a way that does not make the family feel they are being tested: “I am not always clear when I communicate. Do you mind telling me back in your own words what you thought I said so I know we are on the same page?” This also provides an opportunity to answer any new questions that arise. Hearing the information directly from the family can allow the team to clarify any misconceptions and give insight into any emotional responses that the family might have.

4. Respond to Emotion

Discussing serious news in the ICU setting naturally leads to an emotional reaction. The clinician’s ability to notice emotional cues and respond with empathy is a key communication skill in family meetings [13]. Emotional reactions impede individual’s ability to process cognitive information and make it hard to think cognitively about what should be done next.

Physicians miss opportunities to respond to emotion in family meetings [14]. Missed opportunities lead to decreased family satisfaction and may lead to treatment decisions not consistent with the wishes of their loved ones. Empathic responses improve the family-clinician relationship and helps build trust and rapport [15]. Well- placed empathic statements may help surrogates disclose concerns that help the physician better understand the goals and values of the family and patient. Families also can more fully process cognitive information when their emotional responses have been attended to.

Physicians can develop the capacity to recognize and respond to the emotional cues family members are delivering. Intensivists should actively look for the emotions, the empathic opportunity, that are displayed by the family. This emotion is the “data” that will help lead to an empathic response. A family that just received bad news typically responds by showing emotion. Clues that emotions are present include: the family asking the same questions multiple times; using emotional words such as “sad” or “frustrated;” existential questions that do not have a cognitive answer such as “Why did God let this happen?;” or non-verbal cues like tears and hand wringing.

Sometimes the emotional responses are more difficult to recognize. Families may continue to ask for more cognitive information after hearing bad news. Someone keeps asking “Why did his kidney function worsen?” or “I thought the team said the chest x-ray looked better.” It is tempting to start answering these questions with more medical facts. However, if the question comes after bad news, it is usually an expression of frustration or sadness rather than a request for more information. Rather than giving information, it might help to acknowledge this by saying “I imagine this new is overwhelming.”

5. Highlight the Patient’s Voice

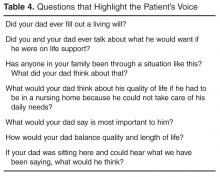

Family meetings are often used to develop new treatment plans (given that the old plans are not working). In these situations, it is essential to understand what the incapacitated patient would say if they were part of the family meeting. The surrogate’s primary role is to represent the patient’s voice. To do this, surrogates need assistance in applying their critically ill loved one’s thoughts and values to complex, possibly life limiting, situations. Surrogate decision makers struggle with the decisions’ emotional impact, as well as how to reconcile their desires with their loved one’s wishes [18]. This can lead them to make decisions that conflict with the loved one’s values [19] as well as emotional sequelae such as PTSD and depression [20].

As families reflect on their loved one’s values, conflicting desires will arise. For example, someone may have wanted to live as long as possible and also values independence. Or someone may value their ability to think clearly more than being physically well but would not want to be physically dependent on artificial life support. Exploring which values would be more important can help resolve these conflicts.

Clinicians should check for understanding while family members are identifying the values of their loved ones. Providing the family with a summary of what you have heard will help ensure a more accurate understanding of these crucial issues. A summary statement might be, “It sounds like you are saying your dad really valued his independence. He enjoyed being able to take care of his loved ones and himself. Is that right?”