Suicide Risk in Older Adults: The Role and Responsibility of Primary Care

Suicide in Older Adults

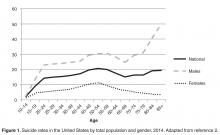

The United States has recently seen increases in suicide rates across the lifespan; from 1999 to 2014, the suicide rate rose by 24% across all ages [3]. Among both men and women aged 65 to 74, the suicide rate increased in this time period [3]. The high suicide rate among older adults is particularly important to address given the increasing numbers of older adults in the United States. By 2050, the older adult population in the United States is expected to reach 88.5 million, more than double the older adult population in 2010 [4]. Additionally, the generation that is currently aging into older adulthood has historically had higher rates of suicide across their lifespan [5]. Given that suicide rates also increase in older adulthood for men, the coming decades may evidence even higher rates of suicide among older adults than previously and it is critical that older adult suicide prevention becomes a public health priority.

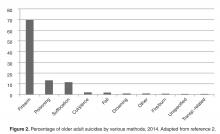

It is also essential to discuss other suicide-related outcomes among older adults, including suicide attempts and suicide ideation. This is critical particularly because the ratio of suicide attempts to deaths by suicide in this age-group is 4 to 1 [1]. This is in contrast to the ratio of attempts to deaths across all ages, which is 25 suicide attempts per death by suicide [1]. This means that suicide prevention must occur before a first suicide attempt is made; suicide attempts cannot be used a marker of elevated suicide risk in older adults or an indication that intervention is needed. Intervention is required prior to suicide risk becoming elevated to the point of a suicide attempt.

It is also critical to recognize that despite the fact that suicide rates rise with age, reports of suicide ideation decrease with age [7,8]. Across all ages, 3.9% of Americans report past-year suicide ideation; however, only 2.7% of older adults report thoughts of suicide [9]. The discrepancy with the increasing rates of death by suicide with age suggest that suicide risk, and thereby opportunities for intervention, may be missed in this age-group [10].

However, older adults may be more willing to report death ideation, as research has found that over 15% of older adults endorse death ideation [11–13]. Death ideation is a desire for death without a specific desire to end one’s own life, and is an important suicide-related outcome, as older adults with death ideation appear the same as those with suicide ideation in terms of depression, hopelessness, and history of suicidal behavior [14]. Additionally, older adults with death ideation had more hospitalizations, more outpatient visits, and more medical issues than older adults with suicide ideation [15]. Therefore, death ideation should be taken as seriously as suicide ideation in older adults [14]. In sum, the high rates of death by suicide, the likelihood of death on a first or early suicide attempt, and the discrepancy between decreasing reports of suicide ideation and increasing rates of death by suicide among older adults indicate that older adult suicide is an important public health problem.

Suicide Prevention Strategies

Many suicide prevention strategies to date have focused on indicated prevention, which concentrates on individuals already identified at high risk (eg, those with suicide ideation or who have made a suicide attempt) [16]. However, because older adults may not report suicide ideation or survive a first suicide attempt, indicated prevention is likely not enough to be effective in older adult suicide prevention. A multilevel suicide prevention strategy [17] is required to prevent older adult suicide [18]. Older adult suicide prevention must include indicated prevention but must also include selective and universal prevention [16]. Selective prevention focuses on groups who may be at risk for suicide (eg, individuals with depression, older adults) and universal prevention focuses on the entire population (eg, interventions to reduce mental health stigma) [16]. To prevent older adult suicide, crisis intervention is critical, but suicide prevention efforts upstream of the development of a suicidal crisis are also essential.

The Importance of Primary Care

Research indicates that primary care is one of the best settings in which to engage in older adult suicide prevention [18]. Older adults are significantly less likely to receive specialty mental health care than younger adults, even when they have depressive symptoms [19]. Additionally, among older adults who died by suicide, 58% had contact with a primary care provider within a month of their deaths, compared to only 11% who had contact with a mental health specialist [20]. Among older adults who died by suicide, 67% saw any provider in the 4 weeks prior to their death [21]. Approximately 10% of older adults saw an outpatient mental health provider, 11% saw a primary care physician for a mental health issue, and 40% saw a primary care physician for a non-mental health issue [21]. Therefore, because older adults are less likely to receive specialty mental health treatment and so often seen a primary care practitioner prior to death by suicide, primary care may be the ideal place for older adult suicide risk to be detected and addressed, especially as many older adults visit primary care without a mental health presenting concern prior to their death by suicide.

Additionally, older adults may be more likely to disclose suicide ideation to primary care practitioners, with whom they are more familiar, than physicians in other settings (eg, emergency departments). Research has shown that familiarity with a primary care physician significantly increases the likelihood of patient disclosure of psychosocial issues to the physician [22]. Primary care providers also have a critical role as care coordinators; many older adults also see specialty physicians and use the emergency department. In fact, older adults are more likely to use the emergency department than younger adults, but emergency departments are not equipped to navigate the complex care needs of this population [23]. Primary care practitioners are important in ensuring that health issues of older adults are addressed by coordinating with specialists, hospitals (eg, inpatient stays, emergency department visits, surgery) and other health services (eg, home health care, physical therapy). Approximately 35% of older adults in the United States experience a lack of care coordination [24], which can negatively impact their health and leave issues such as suicide ideation unaddressed. Primary care practitioners may be critical in screening for mental health issues and suicide risk during even routine visits because of their familiarity with patients, and also play an important role in coordinating care for older adults to improve well-being and to ensure that critical issues, such as suicide ideation, are appropriately addressed.

Primary care practitioners can also be key in upstream prevention. Primary care practitioners are in a unique role to address risk factors for suicide prior to the development of a suicidal crisis. Because older adults frequently see primary care practitioners, such practitioners may have more opportunities to identify risk factors (eg, chronic pain, depression). Primary care practitioners are also trained to treat a broad range of conditions, providing the skills to address many different risk factors.

Finally, primary care is a setting in which screening for depression and suicide ideation among older adults is recommended. The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends screening for depression in all adults and older adults and provides recommended screening instruments, some of which include questions about self-harm or suicide risk [25]. However, this same group has concluded that there is insufficient evidence to support a recommendation for suicide risk screening [26]. Despite this, the Joint Commission recently released an alert that recommends screening for suicide risk in all settings, including primary care [27]. The Joint Commission requirement for ambulatory care that is relevant to suicide is PC.04.01.01: The organization has a process that addresses the patient’s need for continuing care, treatment, or services after discharge or transfer; behavioral health settings have additional suicide-specific requirements. The recommendations, though, go far beyond this requirement for primary care. The Joint Commission specifically notes that primary care clinicians play an important role in detecting suicide ideation and recommends that primary care practitioners review each patient’s history for suicide risk factors, screen all patients for suicide risk, review screenings before patients leave appointments, and take appropriate actions to address suicide risk when needed [27]. Further details are available in the Joint Commission’s Sentinel Event Alert titled, “Detecting and treating suicide ideation in all settings” [27]. Given these recommendations, primary care is an important setting in which to identify and address suicide risk.