Management of Stable Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

From the Division of Pulmonary Critical Care Medicine, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL.

Abstract

- Objective:To review the management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

- Methods: Review of the peer-reviewed literature.

- Results: Effective management of stable COPD requires the physician to apply a stepwise intensification of therapy depending on patient symptoms and functional reserve. Bronchodilators are the cornerstone of management. In addition to pharmacologic therapies, nonpharmacologic therapies, including smoking cessation, vaccinations, proper nutrition, and maintaining physical activity, are an important part of long-term management. Those who continue to be symptomatic despite appropriate maximal therapy may be candidates for lung volume reduction. Palliative care services for COPD patients, which can aid in reducing symptom burden and improving quality of life, should not be overlooked.

- Conclusion: Successful management of stable COPD requires a multidisciplinary approach that utilizes various medical therapies as well as nonpharmacologic interventions.

Key words: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; exacerbation; bronchodilator; lung volume reduction; cough.

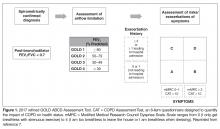

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a systemic inflammatory disease characterized by irreversible obstructive ventilatory defects [1–4]. It is a major cause of morbidity and mortality affecting 5% of the population in the United States and was the third leading cause of death in 2008 [5,6]. The goals in COPD management are to provide symptom relief, improve the quality of life, preserve lung function, and reduce the frequency of exacerbations and mortality. In this review, we will discuss the management of stable COPD in the context of 3 common clinical scenarios.

Case 1

A 65-year-old male with COPD underwent pulmonary function testing (PFT), which demonstrated an obstructive ventilatory defect (forced expiratory volume in 1 second/forced vital capacity ratio [FEV1/FVC], 0.45; FEV1, 2 L [65% of predicted]; and diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide [DLCO], 15 [65% of predicted]). He has dyspnea with strenuous exercise but is comfortable at rest and with minimal exercise. He has had 1 exacerbation in the last year that was treated on an outpatient basis with steroids and antibiotics. His medication regimen includes inhaled tiotropium once daily and inhaled albuterol as needed that he uses roughly twice a week.

What determines the appropriate therapy for a given COPD patient?

What is the approach to building a pharmacologic regimen for the patient with COPD?

The backbone of the pharmacologic regimen for COPD includes short- and long-acting bronchodilators. They are usually given in an inhaled form to maximize local effects on the lungs and minimize systemic side effects. There are 2 main classes of bronchodilators, beta agonists and muscarinic antagonists, and each targets specific receptors on the surface of airway smooth muscle cells. Beta agonists work by stimulating beta-2 receptors, resulting in bronchodilation, while muscarinic antagonists work by blocking the bronchoconstrictor action of M3 muscarinic receptors. Inhaled corticosteroids can be added to long-acting bronchodilator therapy but cannot be used as stand-alone therapy. Theophylline is an oral bronchodilator that is used infrequently due to its narrow therapeutic index, toxicity, and multiple drug interactions.

Who should be on short-acting bronchodilators? What is the best agent? Should it be scheduled or used as needed?

All patients with COPD should be an on inhaled short-acting bronchodilator as needed for relief of symptoms [7]. Both short-acting beta agonists (albuterol and levalbuterol) and short-acting muscarinic antagonists (ipratropium) have been shown in clinical trials and meta-analyses to improve symptoms and lung function in patients with stable COPD [9,10] and seem to have comparative efficacy when compared head-to-head in trials [11]. However, the airway bronchodilator effect achieved by both classes seems to be additive when used in combination and is also associated with less exacerbations compared to albuterol alone [12]. On the other hand, adding albuterol to ipratropium increased the bronchodilator response but did not reduce the exacerbation rate [11–13]. Inhaled short-acting beta agonists when used as needed rather than scheduled are associated with less medication use without any significant difference in symptoms or lung function [14].

The side effects related to using recommended doses of a short-acting bronchodilator are minimal. In retrospective studies, short-acting beta agonists increased the risk of severe cardiac arrhythmias [15]. Levalbuterol, the active enantiomer of albuterol (R-albuterol) developed for the theoretical benefits of reduced tachycardia, increased tolerability, and better or equal efficacy compared to racemic albuterol, failed to show a clinically significant difference in inducing tachycardia [16]. Beta agonist overuse is associated with tremor and in severe cases hypokalemia, which happens mainly when patients try to achieve maximal bronchodilation; the clinically used doses of beta agonists are associated with fewer side affects but achieve less than maximal bronchodilation [17]. Ipratropium can produce systemic anticholinergic side effects, urinary retention being the most clinically significant especially when combined with long-acting anticholinergic agents [18].

In light of the above discussion, a combination of short-acting beta agonist and muscarinic antagonist is recommended in all patients with COPD unless the patient is on a long-acting muscarinic antagonist [7,18]. In the latter case, a short-acting beta agonist used as a rescue inhaler is the best option. In our patient, albuterol was the choice for his short-acting bronchodilator as he was using the long-acting muscarinic antagonist tiotropium.

Are short-acting bronchodilators enough? What do we use for maintenance therapy?

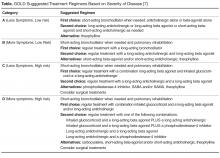

All patients with COPD who are category B or higher according to the modified GOLD staging system should be on a long-acting bronchodilator [7,19]: either a long-acting beta agonist (LABA) or long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA). Long-acting bronchodilators work on the same receptors as their short-acting counterparts but have structural differences. Salmeterol is the prototype for long-acting selective beta-2 agonist. It is structurally similar to albuterol but has an elongated side chain that allows it to bind firmly to the area of beta receptors and stimulate them repetitively, resulting in an extendedduration of action [20]. Tiotropium on the other hand is a quaternary ammonium of ipratropium that is a nonselective muscarinic antagonist [21]. Compared to ipratropium, tiotropium dissociates more quickly from M2 receptors, which is responsible for the undesired anticholinergic effects, while at the same time it binds M1 and M3 receptors for a prolonged time, resulting in extended duration of action [21].

The currently available long-acting beta agonists include salmeterol, formoterol, aformoterol, olodatetol, and indacaterol. The last two have the advantage of once-daily dosing rather than twice [22,23]. LABAs have been shown to improve lung function, exacerbation rate, and quality of life in multiple clinical trials [22–24]. Vilanterol is another LABA that has a long duration of action and can be used once daily [25], but is only available in a combination with umeclidinium, a LAMA. Several LAMAs are approved for use in COPD, including the prototype tiotropium in addition to aclidinium, umeclidinium, and glycopyrronium. These have been shown in clinical trials to improve lung function, symptoms, and exacerbation rate [26–29].

Patients can be started on either a LAMA or LABA depending on patient needs and side effects [7]. Both have comparable side effects and efficacy as detailed below. Concerning side effects, there is conflicting data concerning an association of cardiovascular events with both classes of long-acting bronchodilators. While clinical trials failed to show an increased risk [24,30,31], several retrospective studies showed an increased risk of emergency room visits and hospitalizations due to tachyarrhythmias, heart failure, myocardial infarction, and stroke upon initiation of long-acting bronchodilators [32,33]. There was no difference in risk for adverse cardiovascular events between LABA and LAMA in one Canadian study, and slightly more with LABA in a study using an American database [32,33]. Urinary retention is another possible complication of LAMA supported by evidence from meta-analyses and retrospective studies but not clinical trials and should be discussed with patients upon initiation [34,35]. There have been concerns about increased mortality with the soft mist formulation of tiotropium that were put to rest by the tiotropium safety and performance in Respimat (TIOSPIR) trial, which showed no increased mortality compared to Handihaler [36].