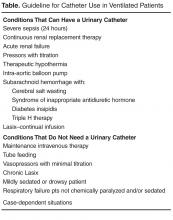

Cutting CAUTIs in Critical Care

Challenges Encountered

Culture change is challenging. The entrenched mindset was that “If a patient is sick enough to be in an ICU, then they are sick enough to need a urinary catheter.” Standard nursing practice typically included placement of a urinary catheter immediately on arrival to the ICU if not already present. Over the years, placing a urinary catheter had become the norm in the ICU, with nurses noting concern about obtaining accurate measurement of urine output and prevention of skin breakdown from incontinence. We had to continually address these concerns to make progress on the project. By providing alternatives to urinary catheters, such as incontinence pads, external male collection devices in varying sizes, moisture barrier products, and scales to measure urine output, nurses were more willing to comply with catheter removal.

We worked with our wound and ostomy nurses to ensure we were providing the proper moisture barrier products and presented research to support that incontinence did not need to lead to pressure ulcers. The wound care team helped with guiding the use of products for incontinent patients to prevent incontinence-associated dermatitis and potential skin breakdown. Our administration financially supported our program, allowing us to bring in and trial supplies. As we identified products for use, we were able to place them into floor stock and make them easily available to nursing. Items such as wicking pads, skin protective creams, and alternatives to catheters were a vital part of our bedside toolkit to maintain our patient’s skin integrity.

Both nurses and physicians were concerned about accurate measurement of output, specifically in surgical patients. The use of scales to weigh and measure output from an incontinent patient’s pads was helpful but sometimes inconvenient. From our surgeons' perspective, not having immediate hourly measurements of urine output to monitor risk for hypovolemia from third spacing of fluid or from abdominal compartment syndrome was not acceptable. Because of this concern, we did not see a decrease in early catheter removal among surgical patients. Daily conversations with nurses and surgeons at the bedside continue to be key to removing catheters as soon as the surgeon is comfortable that the patient is out of risk for hypovolemia.

Outcomes

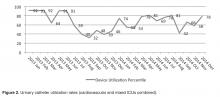

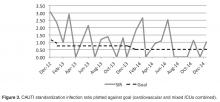

Within the first month we saw an immediate drop in catheter utilization and had zero CAUTIs, but during the next 2 months there was a return to our previous rates (Figure 2 and Figure 3 [figures show combined mixed and cardiovascular ICU rates due to reporting requirements]).

Although nursing is at the heart of this engagement, it is the combined efforts of all disciplines that promote the reduction of CAUTIs and improve patient outcomes. When our CAUTI counts plateaued at 10 annually in 2014–2015, we reached out to physicians and found that we had not adequately educated our medical and surgical staff of our project and goals. With the backing of a supportive and vocal ICU director, physician engagement has increased and there is more attention paid to catheter removal by our ICU intensivists. This collaborative approach has helped lower our rates even further in 2016 (n = 3). We achieved our CAUTI SIR goal of less than 1.0 , and changed our current goal to less than 0.5 (Figure 3).

In addition to greater intensivist engagement, the ED reduced their urinary catheter insertion rate from 12% to 4% for all patients transferring to an inpatient status. As previously mentioned, they are now placing catheters from kits that include urometers, so we do not have to break the integrity of the closed system after the patient it transferred to the ICU. We are also collaborating with surgical services to reduce catheter use. This is still a work in progress that requires collaboration with surgeons and hospitalists in changing departmental norms.