Individualizing Treatment of Hyperglycemia in Type 2 Diabetes

From the University of Arizona College of Pharmacy and the University of Arizona College of Medicine-Tucson, Tucson, AZ.

Abstract

- Objective: To summarize key issues relevant to managing hyperglycemia in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and review a strategy for initiating and intensifying therapy.

- Methods: Review of the literature.

- Results: The 6 most widely used pharmacologic treatment options for hyperglycemia in T2DM are metformin, sulfonylureas, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors, and insulin. Recent guidelines stress the importance of an individualized, patient-centered approach to managing hyperglycemia in T2DM, although sufficient guidance for nonspecialists on how to individualize treatment is often lacking. For patients with no contraindications, metformin should be recommended concurrent with lifestyle intervention at the time of diabetes diagnosis. Due to the progressive nature of T2DM, glycemic control on metformin monotherapy is likely to deteriorate over time, and there is no consensus as to what the second-line agent should be. A second agent should be selected based on glycemic goal and potential advantages and disadvantages of each agent for any given patient. If the patient progresses to the point where dual therapy does not provide adequate control, either a third non-insulin agent or insulin can be added.

- Conclusion: Although research is increasingly focusing on what the ideal number and sequence of drugs should be when managing T2DM, investigating all possible combinations in diverse patient populations is not feasible. Physicians therefore must continue to rely on clinical judgment to determine how to apply trial data to the treatment of individual patients.

Key words: type 2 diabetes; patient-centered care; antihyper-glycemic drugs; insulin; therapeutic decision-making.

Diabetes mellitus affects approximately 29.1 million people, or 9.3% of the U.S. population [1,2]. The high prevalence of diabetes and its associated multiple complications, including cardiovascular disease (CVD), blindness, renal failure, lower extremity amputations, and premature death, lead to a tremendous overall burden of disease. The financial cost is staggering as well, with more than 1 in 5 health care dollars spent on treating diabetes or its complications [3]. The goal of diabetes treatment is to prevent acute complications and reduce the risk of long-term complications. Interventions that have been shown to improve diabetes outcomes include medications for glycemic control and treatment of cardiovascular risk factors, nutrition and physical activity counseling, smoking cessation, immunizations, psychosocial care, and ongoing surveillance and early treatment for eye, kidney, and foot problems [4].

Glycemic management in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), the focus of this review, is growing increasingly complex and has been the subject of numerous extensive reviews [5,6] and published guidelines [4,7]. In the context of an increasing array of available pharmacologic options, there are mounting uncertainties regarding the benefits of intensive glycemic control as well as increasing concerns about potential adverse treatment effects, hypoglycemia in particular. While previous guidelines encouraged specific approaches for most patients, more recent guidelines stress the importance of a patient-centered approach with shared decision-making [4]. Less prescriptive guidelines are more appropriate, given the current state of science, but they also may be viewed as providing insufficient guidance to some providers. It can be overwhelming for a non-specialist to try to match the nuances of antihyperglycemic medications to the nuances of each patient’s preferences and medical characteristics.

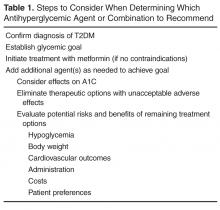

This article examines key issues faced by primary care providers when managing hyperglycemia in patients with T2DM and outlines a stepwise approach to determining the optimal antihyperglycemic agent(s) (Table 1).

Confirm Diagnosis of T2DM

It can be difficult to distinguish between type 1 diabetes mellitus and T2DM in some individuals due to overlapping characteristics. However, correctly classifying a patient’s diabetes at the outset is essential, as the classification helps determine the best treatment regimen and is rarely reconsidered [4,8]. Considerable evidence suggests that misclassification of diabetes occurs frequently [9,10], resulting in patients receiving inappropriate treatment. Clinical characteristics suggestive of T2DM include older age and features of insulin resistance such as obesity, hyper-tension, hypertriglyceridemia, and low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. When these features are not present, an alternate diagnosis should be entertained.

Establish Glycemic Goal

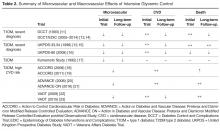

Research over the past decade has led to a growing appreciation of the enormous complexity of hyperglycemia management. During the 1990s, landmark trials such as the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) [11] and UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) [12] demonstrated that improving glucose control could reduce the incidence of microvascular complications [11,12], prompting a lower-is-better philosophy regarding glucose targets. Despite limited evidence to support such thinking, this viewpoint was adopted by the developers of many guidelines. During the following decade more research was devoted to determining whether aggressively lowering a patient’s glucose could also improve macrovascular outcomes. Table 2 summarizes microvascular and macrovascular effects of intensive glycemic control seen in major trials [11–23]. After several major trials [20,22] found only mild cardiovascular benefits and even suggested harm [18], experts and policy makers began to reconsider the value of tightly controlling glucose levels [24]. Since then, other studies have demonstrated that the potential benefits and risks of glucose control are strongly related to individual patient factors, such as age and duration of diabetes, and associated comorbidities, such as CVD and impaired renal function [6].

A one-size-fits-all glycemic goal is no longer recommended. Personalization is necessary, balancing the potential benefits and risks of treatments required to achieve that goal. Whereas an A1C of < 7% is an appropriate target for some individuals with diabetes, glycemic targets may be more or less stringent based on patient features including life expectancy, duration of diabetes, comorbidities, and patient attitude and support system (Table 3) [4].

A particular group in which less stringent goals should be considered is older patients, especially those with complex or poor health status [4,25]. The risk of intensive glycemic control may exceed the benefits in these patients, as they are at higher risk of hypoglycemia and polypharmacy [26]. A goal A1C of 7% to 7.5% is now recommended for healthy older adults, and less stringent A1C goals of 7.5% to 8% and 8% to 8.5% should be considered based on the presence and severity of multiple coexisting chronic illnesses, decreased self-care ability, or cognitive impairment [4,25]. Unfortunately, overtreatment is frequently seen in this group. In a recent study of patients over age 65 years, about 40% of those with complex or poor health status had tight glycemic control with A1C below 6.5% [26]. An analysis of U.S. Veterans Affairs administration data showed that only 27% of 12,917 patients older than 65 with very low A1C (< 6%) and about 21% of those with A1C of 6% to 6.5% underwent treatment deintensification [27].

Initiate Treatment with Metformin

There is strong consensus that metformin is the preferred drug for monotherapy due to its long proven safety record, low cost, weight-reduction benefit, and potential cardiovascular advantages [4,16]. As long as there are no contraindications, metformin should be recommended concurrent with lifestyle intervention at the time of diabetes diagnosis. The recommendation is based on the fact that adherence to diet, weight reduction, and regular exercise is not sustained in most patients, and most patients ultimately will require treatment. Since metformin is usually well-tolerated, does not cause hypoglycemia, has a favorable effect on body weight, and is relatively inexpensive, potential benefits of early initiation of medication appear to outweigh potential risks.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently relaxed prescribing polices to extend the use of this important medication to patients who have mild–moderate, but stable, chronic kidney disease (CKD) [28]. Metformin is recommended as first-line therapy and should be used unless it is contraindicated (ie, estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR] < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2)[4,7,29].