The challenge of managing a cetuximab rash

Accepted for publication November 27, 2018

Correspondence Jondavid Pollock, MD, PhD; jpollock@wheelinghospital.org

Disclosures The authors report no disclosures/conflicts of interest.

©2018 Frontline Medical Communications

doi https://doi.org/10.12788/jcso.0440

Discussion

A cetuximab-induced rash is common. In a 2011 meta-analysis quantifying grades 1 to 4 in severity, about 75% of patients treated with an EGFR inhibitor experienced a rash. Most of the rashes were lower than grade 3, and the drug was either dose-reduced or temporarily held, but it was not generally discontinued.6 Of note is that in a nonselected survey of medical oncologists who were prescribing cetuximab, 76% reported holding the drug owing to rash severity, 60% reported dose reductions for a drug rash, and 32% reported changing the drug because of rash severity.7

In the initial pharmaceutical registration trial, 76% to 88% of patients who received cetuximab developed a rash, 17% of which were at least grade 3. The pharma recommendations for managing the drug rash include a drug delay for up to 2 weeks for a rash of grade 3 or less and to terminate use of the drug if there is no clinical improvement after 2 weeks.8 Biopsies of the rash confirm a suppurative inflammatory reaction separate from an infectious acne reaction,9 resulting in a recommendation to treat with topical steroid therapy. In some circumstances, the drug reaction can become infected or involve the paronychia, often related to Staphylococcus aureus.10 Despite what would otherwise be a problem addressed by anti-inflammatory medical therapy, the clinical appearance of the rash marked by pustules, coupled with the relative immunosuppressed state of a cancer patient, has prompted medical oncologists to prescribe antibiotic therapy.

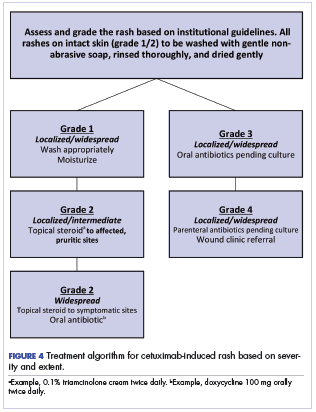

To address the many single-institutional reports on management of the EGFR rash, several guidelines have been published. The earliest guideline – after a report that concurrent cetuximab and radiotherapy was superior to radiotherapy alone in locally advanced head and neck cancer, which documented a 23% incidence of at least grade 3 cutaneous toxicity in the cetuximab arm1 – attempted to score the severity of the rash according to the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI) Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE). Under those criteria, the authors defined grade 2 toxicity as moderate to brisk erythema with patchy moist desquamation, mostly confined to skin folds and creases. Grade 3 toxicity was described as moist desquamation other than skin folds and creases with bleeding induced by minor trauma, and grade 4 skin toxicity was defined as skin necrosis or ulceration of full thickness dermis with spontaneous bleeding from the involved site. The authors went on to describe a grade-related treatment algorithm that included gently washing the skin, keeping it dry, and using topical anti-inflammatory agents, including steroids. Antibiotics should be used in the presence of a suspected infection after culturing the area, and grade 4 toxicity should be referred to a wound care center.11

,In a consensus statement from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, the authors noted that most management recommendations were anecdotal. They recommended against the use of astringents and other drying agents because they exacerbate pain. The ultimate choice of topical steroids or antibiotics was based entirely on subjective judgement given the absence of prospective data.12

A Spanish consensus conference report argued against any prophylaxis against a skin reaction, other than keeping the skin clean and dry.13 The authors of the report recommended against washing the affected skin more than twice a day to avoid excess drying, and they advocated for moisturizers and debridement of skin crusting with hydrogels to reduce superinfection and bleeding.13 The authors also noted that some guidelines have suggested that topical steroids might exacerbate a skin rash,14 but they concluded that topical steroids are beneficial as long as they are used for less than 2 weeks. Any use of antibiotics should be based on clear evidence of an infection.13

In the first modification of the NCI’s CTCAE rash grading scale, an international panel addressed the increasing number of reports in the literature suggesting that the previous toxicity scale was possibly inadequate in its recommendations for appropriate treatment. The initial scale had defined only the skin reaction and not what therapy should be administered; therefore, in the update, the descriptions for grades 1 and 2 toxicity remained unchanged, but oral antibiotics were recommended for grade 3 lesion, and parenteral antibiotics with skin grafting were required with grade 4 toxicity.15

An Asian expert panel suggested modifying the bioradiation dermatitis scale, defining a grade 3 dermatitis as >50% moist desquamation of the involved field with formation of confluent lesions because of treatment. They recommended both topical and oral therapy, wound care, and possible hospitalization in severe cases. The panel suggested topical and systemic steroids and antibiotics.16

Finally, in an Italian consensus report, the members again modified the skin toxicity grading and were notably more aggressive in terms of their management recommendations. They defined grade 2 toxicity as pustules or papules covering 10% to 30% of the body surface area, with potential pruritus or tenderness. They also noted the psychosocial impact of skin toxicities on patients and the limits to their activities of daily living. They recommended vitamin K1 (menadione) cream, topical antibiotics, topical intermediate potency steroids, and oral antibiotic therapy for up to 4 weeks for grade 2 toxicity. Despite this aggressive treatment course, the authors admitted that the utility of topical steroids and antibiotics was unknown. They defined grade 3 toxicity as pustules or papules covering more than 30% of the body surface area, with signs of possible pruritus and tenderness. Activities of daily living and self-care were affected, and there was evidence of a superinfection. The panel suggested use of antibiotics pending culture results, oral prednisone, antihistamines, and oral analgesics. Topical therapy was not included.17 It is noteworthy that only the Italian panel recommended the use of vitamin K1 cream. In a prospective randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial of 30 patients, menadione exhibited no clinical benefit in terms of reducing the severity of cetuximab skin lesions.18

Figure 4 illustrates our institutional approach to treating cetuximab rash based on a combination of the Spanish and NCI approaches.

The ultimate choice of therapy to manage a cetuximab rash must be patient and treatment specific. Our institutional approach, like that of the Spanish series,13 is to avoid chemoprophylaxis against a rash; rather, we recommend daily washing of the skin with a gentle soap followed by thorough rinsing and adequate, nonaggressive drying. Moisturizing the intact skin has been shown to reduce exfoliation, and we have incorporated that approach into our regimen.19

In our patient, whose head and neck radiotherapy tumor volume included a portion of the oral cavity and oropharynx, systemic antibiotic and steroid therapy would likely lead to further complications with the development of oral candidiasis. Therefore, while the severity of the reaction remained a grade 2, it seemed appropriate to treat with topical intermediate potency steroids and skin cleansing only. If the reaction had become more severe, then cultures would have been obtained to guide our decision on antibiotic therapy. Our patient’s response to topical steroids was predictable and effective, and he was able to proceed with his course of cancer therapy.