Gastrointestinal cancers: new standards of care from landmark trials

Received for publication October 2, 2017

Published online ahead of print March 28, 2018

Correspondence

David H Henry, MD; David.Henry@uphs.upenn.edu;

Daniel G Haller, MD, FACP, FRCP; Daniel.Haller@uphs.upenn.edu

Disclosures The authors report no disclosures/conflicts of interest.

Citation JCSO 2018; 16(2): e117-e122

©2018 Frontline Medical Communications

doi https://doi.org/10.12788/jcso.0377

Listen to the audio here

Submit a paper here

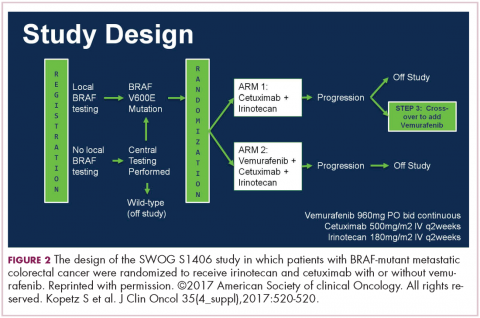

DR HENRY That’s really fascinating, and if not practice changing, then practice challenging. Staying with the mutations idea, in my patients, I’m checking the RAS family and the BRAF mutation, where I’ve learned that’s a particularly bad mutation. I wonder if you might comment on the Kopetz trial, which took a cohort of BRAF mutants and treated them (Figure 2).3 How did that turn out?

DR HALLER It turned out well. We’re turning colon cancer into non–small cell lung cancer in that we’re getting small groups of patients who now have very dedicated care. The backstory here is that there was some thought that you should be treating mutations, not tumor sites. Drugs such as vemurafenib, for example, which is a BRAF inhibitor, worked well in melanoma for the same mutation that’s in colon cancer, V600E. But when vemurafenib was used in the BRAF-mutant patients – these are 10% of the population – median survivorship was one-third that of the rest of the patients, so roughly 12 months. People looked like they were doing worse when vemurafenib was used. They had no benefit.

,Scott Kopetz at MD Anderson (Houston, Texas) is a very good bench-to-bed-and-back sort of doc. He looked at this in cell lines and found that when you give a BRAF inhibitor, you upregulate EGFR so you add an EGFR inhibitor. He did a phase 1 and 1B study, and then in the co-operative groups, a study was done – a randomized phase 2 trial for people who had the BRAF-V600E mutation failing first-line therapy, and then went on to receive either irinotecan single agent or irinotecan plus cetuximab or a triple arm of irinotecan, cetuximab, and vemurafenib. There was a crossover, and so the primary endpoint was progression-free survival. It accrued rapidly.

Again, small study, about 100 patients, but for the double-agent arm, or cetuximab–irinotecan, the median survivorship was 2 months. It was 4.4 months for the combination, so more than double. The response rate quadrupled from 4% to 16%, and the people who had disease control tripled, from 22% to 67%. Many of these patients had bulky disease, BRAF mutations. They need response, so this is a very important endpoint.

Overall survival was not different, in part because it was a crossover, and the crossover patients did pretty well. This is going to move more toward first-line therapy, because we don’t talk about fourth- and fifth-line therapies, TAS-102 or regorafenib. These patients don’t make it to even third line. We’re chipping away at what we think is a very homogenous group of peoples’ metastatic disease. They’re obviously not.

DR HENRY In the BRAF-mutant patient, the vemurafenib might drive them toward EGFR, and then the cetuximab could come in and handle that diversion of the pathway. Fascinating.

DR HALLER The preferred regimen in first-line therapy for a BRAF mutant might be FOLFIRI, cetuximab, and vemurafenib, especially on the left side.

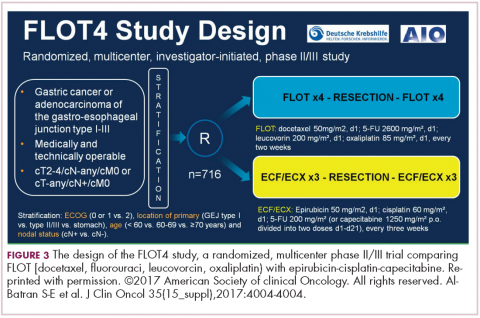

DR HENRY Certainly makes sense. We’ll continue the theme at ASCO of “new standard of care.” Let’s move to gastroesophageal junction. There was a so-called FLOT (5-FU, leucovorin, oxaliplatin, Taxotere) presentation in the neoadjuvant/adjuvant setting, 4 cycles preoperatively and 4 cycles postoperatively. Could you comment on that study?

DR HALLER Gastric cancer for metastatic disease has a very large buffet of treatment regimens, and some just become entrenched, like the ECF regimen with epirubicin (epirubicin, cisplatin, 5-FU), where most people don’t exactly know what the contribution of that drug is, and so some people use EOX (epirubicin, oxaliplatin, capecitabine), some people use FOLFOX, some people use FOLFIRI. It gets a little bit confusing as to whether you use taxanes, platinums, or 5-FU or capecitabine.

The Germans came up with a regimen called FLOT – it’s sort of like FOLFOX with Taxotere attached. They did a very large study comparing it with ECF or ECX (epirubicin, cisplatin, capecitabine; Figure 3).4 The overall endpoint with over 700 patients was survival. This is an adjuvant regimen. Only 37% of people got ECF or ECX postoperatively, and 50% of the FLOT patients got the regimens postoperatively.

One of the reasons FLOT might be more beneficial is that more people were given postoperative treatment, and it’s one reason why many adjuvant regimens are being moved completely preoperatively, because so few people get the planned treatment. The FLOT regimen improved overall survival with a P value of .0112 and a hazard ratio of 0.77. The difference was 35 months versus 50 months. With the uncertainty as to what epirubicin actually does and the fact that it’s been around for a while and that fewer people receive postoperative treatment, with that 15-month benefit, if you’re using chemotherapy alone, and there’s no radiotherapy component for true gastric cancer, this is a new standard of care.

DR HENRY I struggle with this in my patients as well. This concept of getting more therapy preoperatively to those who can’t get it postoperatively certainly resonates with most of us in practice.

DR HALLER If I were redesigning the trial, I would probably say just give 4-6 cycles of treatment, and give it all preoperatively. In rectal cancer, there’s the total neoadjuvant approach, where it’s being tested in people who get all their chemotherapy first, then chemoradiotherapy, then surgery, and you’re done.

DR HENRY Yes, right. Thank you for mentioning that. Staying with the gastric GE junction, you couldn’t get away from ASCO this year without hearing about the checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapies in this population. In the CHECKMATE-142 trial with nivolumab versus placebo, response rates were good, especially in the MSI-high (microsatellite instability). Could you comment on that study?

DR HALLER We already know that in May and July 2017, pembrolizumab and nivolumab were both approved for any MSI-high solid tumor based on phase 2 data only, and based on response. That’s the first time we’ve seen that happen. It’s remarkable. For nivolumab, the approval was based on 53 patients with MSI-high metastatic colon cancer. So these were people who failed standard therapy and got nivolumab by standard infusion every 2 weeks. The overall response rate was almost 30% in this population, which is typically quite resistant to any treatment, so one expects much lower response rates with anything in that setting – chemotherapy, TAS-102, regorafenib, et cetera (Table).5