Hospitalizations for fracture in patients with metastatic disease: primary source lesions in the United States

Background Breast, lung, thyroid, kidney, and prostate cancers have high rates of metastasis to bone in cadaveric studies. However, bone metastasis at time of death may be less clinically relevant than occurrence of pathologic fracture and related morbidity. No population-based studies have examined the economic burden from pathologic fractures.

Objectives To determine primary tumors in patients hospitalized with metastatic disease who sustain pathologic and nonpathologic (traumatic) fractures, and to estimate the costs and lengths of stay for associated hospitalizations in patients with metastatic disease and fracture.

Methods The Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project’s National (Nationwide) Inpatient Sample was used to retrospectively identify patients with metastatic disease in the United States who had been hospitalized with pathologic or nonpathologic fracture during from 2003-2010. Patients with pathologic fracture were compared with patients with nonpathologic fractures and those without fractures.

Results Of 674,680 hospitalizations of patients with metastatic disease, 17,313 hospitalizations were for pathologic fractures and 12,770 were for nonpathologic fractures. The most common primary cancers in patients hospitalized for fractures were lung (187,059 hospitalizations; 5,652 pathologic fractures; 3% of hospitalizations were for pathologic fractures), breast (124,303; 5,252; 4.2%), prostate (79,052; 2,233; 2.8%), kidney (32,263; 1,765; 5.5%), and colorectal carcinoma (172,039; 940; 0.5%). Kidney cancer had the highest rate of hospitalization for pathologic fracture (24 hospitalizations/1,000 newly diagnosed cases). Patients hospitalized for pathologic fracture had higher billed costs and longer length of stay.

Limitations Hospital administrative discharge data includes only billed charges from the inpatient hospitalization.

Conclusion Metastatic lung, breast, prostate, kidney, and colorectal carcinoma are commonly seen in patients hospitalized with pathologic fracture. Pathologic fracture is associated with higher costs and longer hospitalization.

Funding Grants from the NIH (K08 AR060164-01A), American Society for Surgery of the Hand Hand Surgeon Scientist Award grant, and University of Rochester Medical Center Clinical & Translational Science Institute grants, in addition to institutional support from the University of Rochester and Pennsylvania State University Medical Centers.

Accepted for publication November 21, 2017

Correspondence openelfar@gmail.com

Disclosures The authors report no disclosures/conflicts of interest.

Citation JCSO 2018;16(1):e14-e20

©2018 Frontline Medical Communications

doi https://doi.org/10.12788/jcso.0385

Related article

Analgesic management in radiation oncology for painful bone metastases

Submit a paper here

Results

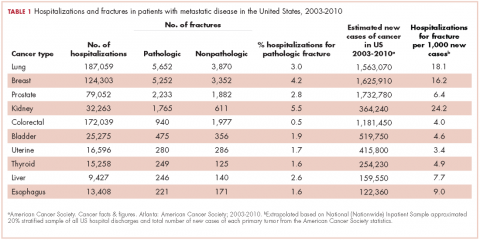

From 2003-2010 there were 674,680 hospitalizations in patients with metastatic cancer that met the inclusion criteria. Hospitalization was most frequent for lung cancer (187,059 admissions), colorectal cancer (172,039), and breast cancer (124,303; Table 1).

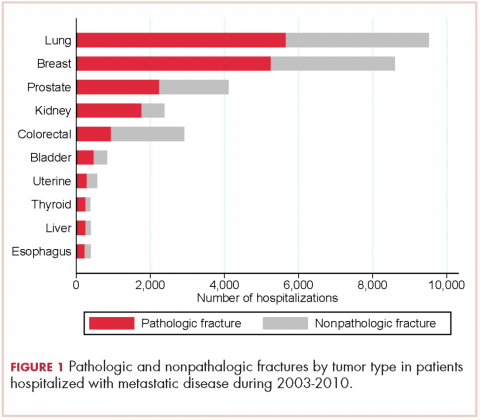

There were 17,303 hospitalizations with pathologic fracture and 12,770 hospitalizations with nonpathologic fracture (Figure 1).

,Among the most commonly occurring primary cancers in hospitalizations with pathologic fracture were lung, breast, prostate, kidney, and colorectal cancers (Table 1).

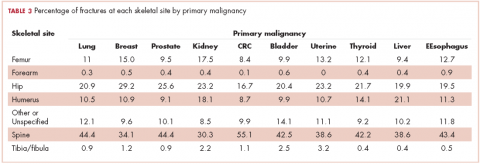

Relative to the annual incidence,15 kidney, lung, and breast cancer had the highest rates of hospital admission for pathologic fracture during the study period. Hospital admission with pathologic fracture was more common than nonpathologic fracture for every type of metastatic disease except colorectal and uterine cancer. Pathologic fracture in patients with metastatic disease was most likely to occur in the spine, hip, and femur (Table 2), and ratio of anatomic sites fractured was relatively consistent across each of the 10 primary malignancies (Table 3).

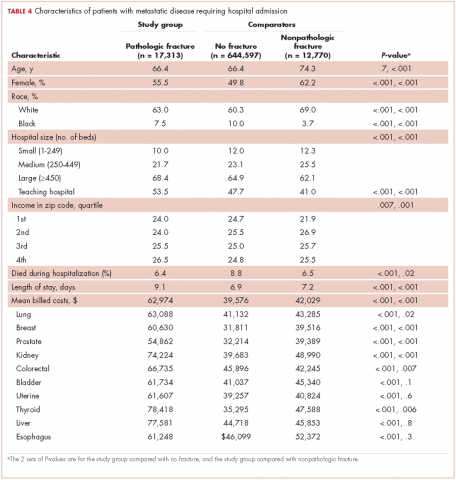

Demographic characteristics of patients in the 3 study groups are shown in Table 4. Patients with pathologic fracture were more likely than those in the no-fracture group to be white (63.0% vs 60.3%, respectively; P < .001) and female (55.5% vs 49.8%; P < .001), but were similar in age (66.4 years; P = 0.7). In-hospital mortality was lower in the pathologic fracture group compared with the no-fracture group (6.4% vs 8.8%; P < .001). People in the pathologic fracture group were more likely than others to be treated at a teaching hospital (P < .001) with ≥450 beds (P < .001), and reside in a zip code with higher income (P < .01).

Pathologic fracture hospitalizations, on average, had higher billed costs and longer length of stay ($62,974, 9.1 days; Table 4), compared with the no-fracture group ($39,576, 6.9 days; both P < .001) and the nonpathologic fracture group ($42,029, 7.2 days; both P < .001). Pathologic fracture in patients with thyroid, liver, and kidney cancer was associated with the highest costs of hospitalization.

In patients with metastatic disease, differences were found between those with pathologic and nonpathologic fractures: those with pathologic fracture were younger (66.4 vs 74.3 years; P < .001), less likely to be white (63.0% vs 69.0%; P < .001), and more commonly treated at a large hospital (68.4% vs 62.1%; P < .001) or a teaching hospital (53.5% vs 41.0%; P < .001).

Discussion

Other investigators have looked at risk factors for pathologic fracture, such as degree of bone involvement, location, and the presence of lytic versus blastic disease, as well as the optimal management of such patients.16-20 In those analyses, there is an emphasis on large, lytic lesions with cortical destruction in weight-bearing long bones, and on functional pain as a key determinant of fracture risk. Although the guidelines outlined by Mirel and others are helpful in predicting fractures, they are not widely applied by practicing oncologists.18 Oncologists and surgeons lack foolproof criteria to predict impending pathologic fracture despite evidence that the pathologic fracture event greatly increases mortality and morbidity.1,4,21,22 As far as we know, this is the first study to determine which types of primary carcinomas were most associated with pathologic fracture requiring hospitalization. This finding will hopefully raise awareness among doctors who care for these patients to be particularly conscientious with patients who present with symptoms of bone pain with activity (functional bone pain) or with lytic disease in the long bones. The results of the present study are similar to those from cadaveric studies, which emphasize the importance of lung, breast, prostate, and kidney cancers as primary tumors that metastasize to bone and lead to pathologic fracture. A novel finding is the nearly 4-fold greater number of pathologic fractures from colorectal carcinoma than thyroid carcinoma.

The importance of detecting patients at risk for pathologic fracture is now more relevant than ever because there are treatment modalities that are readily available to patients with metastatic bone involvement. Two classes of medications, the RANK-ligand inhibitors and bisphosphonates, reduce the number of skeletal events, such as pathologic fracture, in patients with metastatic disease to bone.23-26 However, most of those studies focused on the 3 most common carcinomas (breast, lung, and prostate) to metastasize to bone and cause pathologic fracture. There is greater variability in the prophylactic treatment of other forms of cancer that have metastasized to bone amongst oncologists.

Despite a lower proportion of hospitalizations for fracture in patients with CRC than for thyroid carcinoma (0.5% vs 1.6%, respectively), there were more pathologic fractures from CRC than from thyroid carcinoma because there are far more cases of CRC. SEER data estimate that in 2014 there were 62,000 cases of thyroid cancer and 1,890 deaths, compared with 136,000 cases of CRC and 50,000 deaths.10 Previous findings have shown that bone metastasis from CRC is more common than originally thought, based on autopsies of CRC patients.3 However, the lower rate of bone metastasis in CRC compared with other malignancies has led to a decreased focus on skeletal-related events in CRC. Our results suggest vigilance to bone health is warranted in patients with metastatic CRC. A novel finding is that patients with metastatic CRC also have a high number of hospital admissions for nonpathologic fracture. In establishing that patients with metastatic CRC with bone involvement have a real and significant risk of developing both pathologic and nonpathologic fractures, it may alter the treatment practice for these patients going forward, with greater consideration for an antiresorptive therapy, fall prevention education, or other preventive modalities, such as external-beam radiation therapy after it has been established that patients have metastatic bone disease.

There were some demographic differences between patients with metastatic disease who sustain pathologic fractures and those who do not fracture or sustain nonpathologic fractures. Patients with pathologic fracture were younger than those with nonpathologic fractures, and patients who sustained any fracture were more likely to be white than were patients in the no-fracture group. Known osteoporosis risk factors including older, female, and white with Northern European descent.27 Those findings emphasize the importance of osteoporosis screening and fracture prevention in patients with metastatic disease in general, regardless of the presence of bony metastasis. The present study found that patients who reside in zip codes areas with higher incomes were at slightly increased risk of hospitalization for pathologic fracture. Economic disparities in access to health care and cancer care are well documented,28 and the basis for this finding is a direction for future research.

Both mean billed costs and length of stay were greatest in the pathologic fracture group. The large number of admissions for no-fractured patients may be a final opportunity for intervention and preventative measures in this fragile population. Improved surveillance for bony lesions and attention to pain, especially at night, or unexplained hypercalcemia may help with early diagnosis and prevent some pathologic fractures. Patients with pathologic fracture often undergo additional treatments such as radiation therapy or chemotherapy. These additional treatments may partially explain the higher billed costs associated with inpatient hospitalization; future studies may be able to elucidate treatment differences or other reasons for the increased costs associated with pathologic fractures and identify targets to reduce expenditures.