Patient navigators’ personal experiences with cancer: does it have an impact on treatment?

As patient navigation has become the standard of cancer diagnostic and treatment practices, there is a need to develop competencies and standards for hiring and training navigators, but it is not clear which professional training and skill sets and what personal experiences are most useful to becoming an effective navigator. In this paper, the authors consider whether patient navigation promotes more timely diagnostic care if the navigator has personal experience with cancer.

Accepted for publication February 9, 2016

Correspondence Carolyn.Rubin@tufts.edu

Disclosures The authors report no disclosures/conflicts of interest.

Citation JCSO 2018;16(1):e43-e46

©2018 Frontline Medical Communications

doi https://doi.org/10.12788/jcso.0266

Related articles

Impact of nurse navigation on timeliness of diagnostic medical services in patients with newly diagnosed lung cancer

Predictors of resolution in navigated patients with abnormal cancer screening tests

Submit a paper here

Cox proportional hazard models and adjusted hazard ratios were developed and calculated to examine the impact of navigator’s personal experience with cancer on time to resolution, controlling for patient gender, race, age, and cancer type in the models. The analysis controlled for the individual effect of navigators through clustering. We used P < .05 as the cut-off for significance, and used Stata 10.1 (StataCorp, College Station Texas 77845) for all analyses.

Results

Our analytic sample included the 3,975 patients with only 1 navigator over the course of the study, 79% of the navigation (n = 5,063) arm. Most of the patients were women (93%), and most were from racial and ethnic minority communities. Most patients spoke English (60%), with Spanish (33%) as the next most common language. Most patients were publically insured (38%) or uninsured (40%) (Table 1).

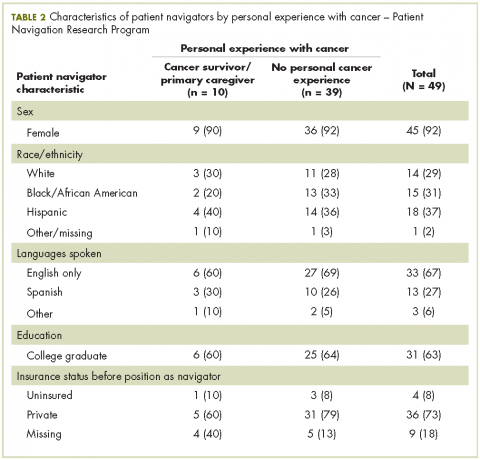

Of the total 49 navigators, 6 were cancer survivors and 4 were primary caregivers to a family member with cancer; an additional 19 reported that they had family members with cancer (Table 2). Most of the navigators were women. The racial/ethnic distribution mirrored the populations they served: white (29%); black or African American (31%); and Hispanic (37%). English was the only spoken language of 67% of the navigators; 27% spoke Spanish, and 6% reported speaking another language. Most had a college degree (63%).

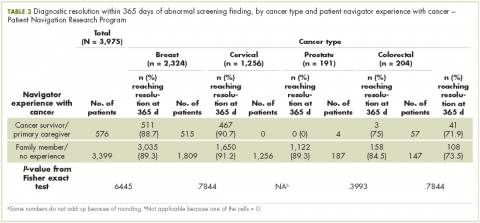

The unadjusted bivariate comparison of patients who achieved diagnostic resolution within 365 days, by navigator experience with cancer, are shown in Table 3. We found no difference in time to diagnostic resolution for those patients for whom navigators had personal experience with cancer compared with those whose navigators had no experience. When stratified by type of cancer screening abnormality (breast, cervical, prostate, or colorectal), the results also did not reveal a significant difference in the proportion of patients achieving diagnostic resolution by 365 days by navigator experience with cancer.

In the Cox proportional hazard model adjusting for patient gender, age, race/ethnicity, cancer type, and adjusting for navigator using clustering, there was no difference between patients whose navigators had experience with cancer care, and those who did not (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.03; 95% confidence interval, .83-1.3). The level of education of navigators was not significantly associated with time to diagnostic resolution for patients.

Discussion

Although several cancer support programs have explicitly used cancer survivors as patient navigators or other supports for patients in active cancer care, there are scant data on whether this expertise improves care. Our study was not able to identify that navigators with previous experience with cancer care, either as a patient or as the primary caregiver, was associated with improved time to diagnostic resolution.

As patient navigation has become the standard of cancer diagnostic and treatment practices, there is a need to develop competencies and standards for hiring and training navigators. Part of this hiring process is to determine what past experience and training are relevant for effective navigation. There is little previous research on relevant skills of navigators, with only one study having demonstrated that language and racial/ ethnic concordance between patients and navigators was associated with more timely care. The national PNRP program hired mostly lay navigators with minimal medical experience, but with affiliations to the communities of the patients receiving care. Our program has demonstrated that lay individuals can be trained in the logistic aspects of navigation.5 Although it may seem intuitive that the experience of being a cancer survivor may make a navigator more empathetic, it is also possible that being too close to the experience of survivorship can also pose challenges to a navigator. Alternatively, navigation may be equally effective with proper training regardless of previous experience with cancer.

Our study is limited to addressing the outcome of timely resolution in the diagnostic phase of care after abnormal cancer screening. It is possible that past experience with cancer care will be beneficial when providing navigation for cancer care. While this study represents one of the largest groups of navigators who have been studied, the small sample may have limited our ability to detect differences. Our study has the benefit of a diverse group of navigators from a nationally representative, multi-site study. We suggest that prior experience with cancer care is not a prerequisite to supporting diagnostic care after abnormal cancer screening. Providing appropriate training to navigators may be sufficient to ensure effective and appropriate care is provided by patient navigators.