Treatment of Biliary Tract Cancers

Pathology and Grading

The majority of BTCs are adenocarcinomas, corresponding to 90% of cholangiocarcinomas and 99% of gallbladder cancers.27,28 They are graded as well, moderately, or poorly differentiated.2 Adenosquamous and squamous cell carcinoma are responsible for most of the remaining cases.2,29 Cholangiocarcinomas are divided into 3 types, defined by the Liver Cancer Study Group of Japan: (1) mass-forming, (2) periductal-infiltrating, and (3) intraductal-growing.30,31 Mass-forming intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas are characterized morphologically by a homogeneous gray-yellow mass with frequent satellite nodules and irregular but well-defined margins.17,30 Central necrosis and fibrosis are also common.30 In the periductal-infiltrating type, tumor typically grows along the bile duct wall without mass formation, resulting in concentric mural thickening and proximal biliary dilation.30 Intraductal-growing papillary cholangiocarcinoma is characterized by the presence of intraluminal papillary or tubular polypoid tumors of the intra- or extrahepatic bile ducts, with partial obstruction and proximal biliary dilation.30

Cholangiocarcinoma

Case Presentation

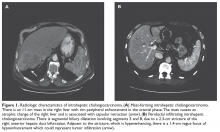

A previously healthy 59-year-old man presents to his primary care physician with a 3-month history of dull right upper quadrant pain associated with weight loss. The patient is markedly cachectic and abdominal examination reveals upper quadrant tenderness. Laboratory exams are significant for elevated alkaline phosphatase (500 U/L; reference range 45–115 U/L), cancer antigen 19-9 (CA 19-9, 73 U/mL; reference range ≤ 37 U/mL), and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA , 20 ng/mL; reference range for nonsmokers ≤ 3.0 ng/mL). Aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, total bilirubin, and coagulation studies are within normal range. Ultrasound demonstrates a homogeneous mass with irregular borders in the right lobe of the liver. Triphasic contrast-enhanced CT scan demonstrates a tumor with ragged rim enhancement at the periphery, and portal venous phase shows gradual centripetal enhancement of the tumor with capsular retraction. No abdominal lymph nodes or extrahepatic tumors are noted (Figure 1, Image A).

- What are the next diagnostic steps?

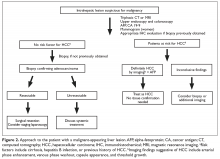

The most critical differential diagnosis of solid liver mass in patients without cirrhosis is cholangiocarcinoma and metastases from another primary site.32 Alternatively, when an intrahepatic lesion is noted on an imaging study in the setting of cirrhosis, the next diagnostic step is differentiation between cholangiocarcinoma and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).32 Triphasic contrast-enhanced CT and dynamic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are key diagnostic procedures.32,33 In the appropriate setting, classical imaging features in the arterial phase with washout in portal venous or delayed phase can be diagnostic of HCC and may obviate the need for a biopsy (Figure 2).

Typical radiographic features of cholangiocarcinoma include a hypodense hepatic lesion that can be either well-defined or infiltrative and is frequently associated with biliary dilatation (Figure 1, Image A).33 The dense fibrotic nature of the tumor may cause capsular retraction, which is seen in up to 20% of cases.17 This finding is highly suggestive of cholangiocarcinoma and is rarely present in HCC.33 Following contrast administration, there is peripheral (rim) enhancement throughout both arterial and venous phases.32–34 However, these classic features were present in only 70% of cases in one study.35 Although intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas are most commonly hypovascular, small mass-forming intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas can often be arterially hyperenhancing and mimic HCC.33 Tumor enhancement on delayed CT imaging has been correlated with survival. Asayama et al demonstrated that tumors that exhibited delayed enhancement on CT in more than two-thirds of their volume were associated with a worse prognosis.36

Patients without cirrhosis who present with a localized lesion of the liver should undergo extensive evaluation for a primary cancer site.37 CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis with contrast should be obtained.37 Additionally, mammogram and endoscopic evaluation with esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) and colonoscopy should be included in the work-up.37

Preoperative tumor markers are also included in the work-up. All patients with a solid liver lesion should have serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels checked. AFP is a serum glycoprotein recognized as a marker for HCC and is reported to detect preclinical HCC.38 However, serum concentrations are normal in up to 40% of small HCCs.38 Although no specific marker for cholangiocarcinoma has yet been identified, the presence of certain tumor markers in the serum of patients may be of diagnostic value, especially in patients with PSC. CA 19-9 and CEA are the best studied. Elevated levels of CA 19-9 prior to treatment are associated with a poorer prognosis, and CA 19-9 concentrations greater than 1000 U/mL are consistent with advanced disease.39,40 One large series evaluated the diagnostic value of serum CEA levels in 333 patients with PSC, 13% of whom were diagnosed with cholangiocarcinoma.34 A serum CEA level greater than 5.2 ng/mL had a sensitivity of 68.0% and specificity of 81.5%.38

If a biopsy is obtained, appropriate immunohistochemistry (IHC) can facilitate the diagnosis. BTC is strongly positive for CK-7 and CK-19.41 CK-7 positivity is not specific and is also common among metastatic cancers of the lung and breast; therefore, in some cases cholangiocarcinoma may be a diagnosis of exclusion. Immunostaining for monoclonal CEA is diffusely positive in up to 75% of cases.41 An IHC panel consisting of Hep Par-1, arginase-1, monoclonal CEA, CK-7, CK-20, TTF-1, MOC-31, and CDX-2 has been proposed to optimize the differential diagnosis of HCC, metastatic adenocarcinoma, and cholangiocarcinoma.41