Differences in psychosocial stressors between black and white cancer patients

Background Screening patients with cancer for psychosocial distress enables providers to make referrals to resources early in the course of treatment. There is some evidence of differential impact of cancer on mental health between racial/ethnic groups, but the results are not consistent.

Objectives To examine differences in overall distress and individual psychosocial stressors between black and white cancer patients at first visit to the cancer center.

Methods This study included all invasive cancer patients from an urban, academic cancer center in the Midwest who completed the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Distress Thermometer from January 1, 2015 to February 19, 2016. Comparisons were made on overall distress score and for each individual stressor in the instrument. Categorical variables were compared using chi-square or Fisher exact test. Logistic regression was used to predict high distress by race adjusting for sex, age, and cancer type.

Results A total of 933 patients with invasive cancer completed the NCCN distress screening tool. The full sample was 16.9% black, and 32.6% of the sample indicated high distress on their first visit. There was no difference in overall distress score between black and white patients. Black patients more frequently identified housing, ability to have children, and loss of interest as sources of distress, whereas white patients more often identified treatment decisions and nervousness.

Limitations Limitations include limited capacity to explore demographic differences in our sample; some patients did not receive the distress screening tool thus some cancer sites are proportionally more represented in the sample.

Conclusions The findings do not indicate overall distress differences between black and white patients, but they do indicate differences in the source of distress, possibly indicating different resource needs or intervention strategies between black and white cancer patients.

Accepted for publication July 14, 2017

Correspondence Leslie Hinyard, PhD, MSW; hinyardl@slu.edu

Disclosures The authors report no disclosures/conflicts of interest.

Citation JCSO 2017;15(6):e314-e320

©2017 Frontline Medical Communications

doi https://doi.org/10.12788/jcso.0366

Related articles

The effect of centralizing breast cancer care in an urban public hospital

Comprehensive assessment of cancer survivors’ concerns to inform program development

Submit a paper here

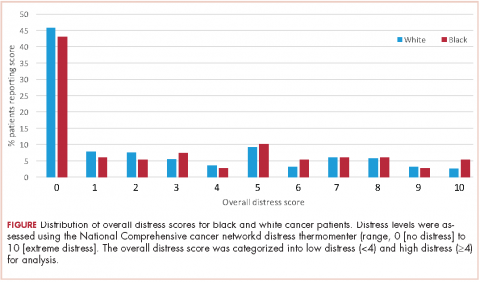

Two primary outcomes were assessed: overall distress, and each individual problem indicator. Overall distress was assessed using the thermometer visual analog rating (the thermometer rating of the NCCN screening tool) where possible values range from 0 (no distress) to 10 (extreme distress). The overall distress score was categorized into low distress (<4) and high distress (≥4) for analysis. The response options for individual stressors on the problem list are Yes or No for each of 17 discrete stressors: child care, housing, insurance/financial, transportation, work/school, treatment decisions, dealing with children, dealing with partner, ability to have children, family health issues, depression, fears, nervousness, sadness, worry, loss of interest, and spiritual/religious concerns. Physical complaints were not assessed in this study. Comparisons were made between white and black patients on overall distress score as well as for each individual psychosocial stressor.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics (counts and proportions or means and standard deviations) were calculated stratified by race. Categorical variables were compared by race using chi-square or Fisher exact test. Logistic regression was used to predict high distress by race adjusting for sex, age, and cancer type. All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 (Cary, NJ).

This study was reviewed and approved by the Saint Louis University Institutional Review Board (protocol number 26269).

Results

A total of 933 patients with cancer completed the NCCN distress screening tool. Of that total, 45 patients did not complete the overall distress score thermometer, but did complete the checklist of individual stressors. Those 45 patients were excluded from the logistic regression analysis for overall distress score, but included on comparisons of individual stressors. The distribution of overall distress scores by race can be seen in the Figure.

Briefly, the full sample was 16.9% black and 38.8% female. In all, 32.6% of the sample indicated high distress on the distress thermometer at their first visit. Demographics for the participants stratified by race are reported in Table 1 (see PDF).There was no statistically significant difference in the gender or age distribution between black and white patients. Cancer distribution did vary by race. Black patients were proportionally more represented in gastrointestinal cancers, hepatobiliary cancers, sarcomas, breast cancer, and genitourinary cancers. White patients were proportionally more represented in melanoma, nonmelanoma skin cancers, and hematologic cancers.

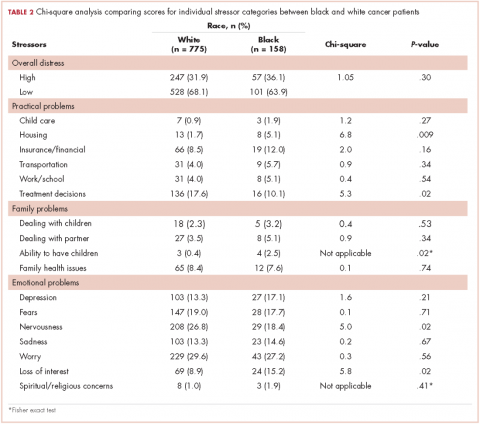

Table 2 presents bivariate comparisons on overall distress and individual stressors between black and white patients. There was no difference in the high distress between black and white patients in bivariate analysis (31.9% and 36.1%, respectively, P = .30). However, there were differences in the individual stressors identified for each racial group (Table 2). White patients, compared with black patients, more frequently identified treatment decisions (17.6% vs 10.1%, P = .02) and nervousness (26.8% vs 18.4%, P = .02) as sources of distress. Black patients, compared with white patients, more frequently identified housing (5.1% vs 1.7%, P = .009), the ability to have children (2.5% vs 0.4%, P =.02), and loss of interest (15.2% vs 8.9%, P = .02) as sources of distress. Distress scores did not differ between black and white patients for child care, insurance or financial issues, transportation, work or school, dealing with children, dealing with partners, family health issues, depression, fears, sadness, worry, or spiritual or religious concerns.

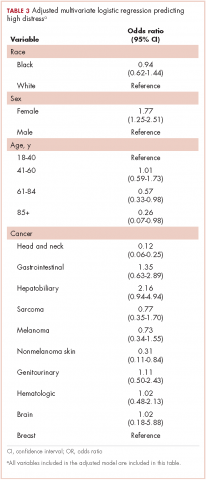

Table 3 presents the results from the logistic analysis predicting high distress. In adjusted analysis, black race did not predict high distress (OR, 0.94; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.62-1.44). High distress was associated with sex, age, and some cancer categories. Women had 77% higher odds of high distress compared with men (OR, 1.77; 95% CI, 1.25-2.51).

Compared with patients aged 18-44 years, patients aged 61-84 had 43% lower odds of high distress (OR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.33-0.98), and patients aged 85 and older had 74% lower odds of high distress (OR, 0.26; 95% CI, 0.07-0.98). There was no statistically significant difference between patients aged 18-40 and those aged 41-60 for high distress (OR, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.59-1.73).

Discussion

Management of patients with cancer continues to evolve. Although a tremendous amount of importance is still placed on the pathophysiology of cancer and its prescribed treatments, more emphasis is being assigned to the physical and psychosocial effects of cancer on these patients. In 2008, the Institute of Medicine published a report that examined the psychosocial health of patients with cancer.14 The report recommended that all cancer care should ensure the provision of appropriate psychosocial health services by facilitating effective communication between patients and care providers, identifying each patient’s psychosocial health needs, coordinating referrals for psychosocial services and monitoring efficacy of psychosocial interventions. The inclusion of psychosocial distress screening in all cancer programs accredited by the ACS CoC helped to prioritize the identification and treatment of psychosocial issues for all cancer patients.