The effect of centralizing breast cancer care in an urban public hospital

Background Quality of care and patient outcomes improve when cancer care is comprehensively centralized. Most patients of lower socioeconomic status in New York City do not receive their cancer care in centralized cancer centers because of the way the medical insurance is structured. In 2002, the Queens Cancer Center was established at Queens Hospital Center in the borough of Queens, to provide consolidated medical, surgical, radiation, gynecologic, and urologic oncology services.

Objective To establish whether breast cancer care changed after the establishment of the cancer center by comparing the changes or improvements in treatment modalities and outcomes before and after the center was established.

Methods We conducted a retrospective chart review of all patients with stage I, II, or III breast cancer treated in 2000, before the comprehensive center was established, and 2008, after its establishment.

Results Several factors changed, including an increase in the number of patients diagnosed with earlier-stage breast cancer, an increase in the use of lumpectomies, and an increase in survival for patients with stage 3 disease.

Limitations Retrospective study

Conclusions Care for breast cancer patients can be improved by centralizing their care.

Accepted for publication April 21, 2017

Correspondence

M Margaret Kemeny, MD, FACS;

kemenym@nychhc.org

Disclosures The author reports no disclosures/conflicts of interest.

Citation JCSO 2017;15(5):e263-e267

©2017 Frontline Medical Communications

doi https://doi.org/10.12788/jcso.0344

Submit a paper here

When cancer care is centralized in a comprehensive fashion, the quality of care and the outcomes improve.1,2 Unfortunately, because of the medical insurance structure in New York City, most patients of lower socioeconomic status do not receive their cancer care in such dedicated cancer centers. In New York City, the majority of the underserved vulnerable populations – that is, those without health insurance – receive their care from the public hospital system known as NYC Health and Hospitals. Cancer care in this system is not centralized and may result in fragmented implementation of various modalities of treatment. In addition, because there is no centralized care, needs such as early screening and prevention programs are often not addressed. This problem was evident in Queens in 2000 and before when many patients with late-stage cancers were presenting for cancer care. Queens, which is one of the 5 boroughs of New York City, has more than 2.3 million residents. It has 2 public hospitals, Elmhurst Hospital Center and Queens Hospital Center (QHC). In 2001, the plan was devised for the establishment of a cancer center at QHC, mainly because of the high rate of late-stage cancers that were being seen at presentation and recognition of the need for more comprehensive care. In 2002, the Queens Cancer Center (QCC) began to see patients. QCC is a single facility that provides medical, surgical, radiation, gynecologic, and urologic oncology all in one area of the QHC.

This study is an investigation of the possible impact on care for breast cancer patients of low socioeconomic status who were treated at a comprehensive cancer center, with specific consideration of the change or improvement in treatment modalities and outcomes. Data on treatment modalities and outcomes of cancer patients who were treated at the QHC during 2000, before the QCC was set up, were compared with data of patients treated during 2008 (2008 was selected because we have 5-year survival data for those patients). The public hospital system treats all patients regardless of their ability to pay, so the majority of patients in the system are of lower socioeconomic status. In addition, 92% of the patients seen QHC are from a minority population. These are the populations that tend to have a worse prognosis and often are not given optimal treatment.3 The payer mix of patients in the public hospital system is different than that of private hospitals. Most of the patients present at the hospital with no insurance and if they are diagnosed with cancer they may be converted to emergency Medicaid. About 10% of patients will not be converted because of their document status.

Patients and methods

We used the Queens Hospital Tumor Registry to identify the patients who had been diagnosed with and treated for breast cancer in 2000 and 2008. The electronic medical records were reviewed, and in the case of the 2000-year patients, the written charts were also reviewed. The study was approved by the Mount Sinai institutional review board. It was not necessary to obtain patient consent because it was a retrospective study.

,Only patients diagnosed with stage 0, I, II, or III breast cancer who received their treatment at QHC were included in the study. Patients who were seen in consultation at QHC but not treated there were excluded. Statistics were done using the 2x2 chi-squared SPSS analysis; a P value of .05 was considered significant. The survival data was analyzed using SAS.

Results

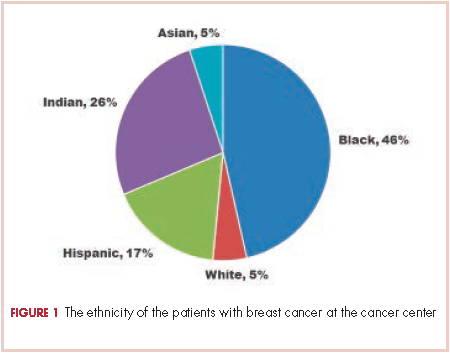

There were 24 evaluable patients in 2000 and 78 evaluable patients in 2008 who had stage 0, I, II, or III primary breast cancer and were treated at QHC. The average age of the patients in 2000 was 53.5 years and 54.7 years in 2008. The mean age for both groups was 55 years. The patients were ethnically diverse in both groups with 46% black, 17% Hispanic, 25% ethnic Asian Indian, and 6% white (Figure 1).

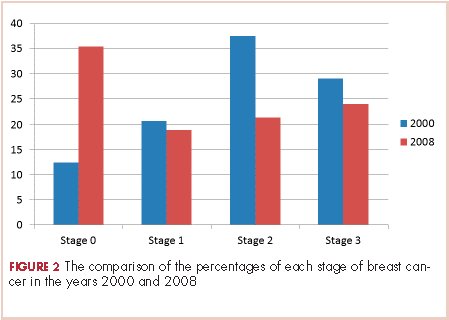

The payer mix in 2000 was 9 patients (37.5%) self-pay, 7 (29%) Medicaid, and 8 (33%) Medicare. In 2008, 11 patients (14%) were self-pay, 46 (59%) Medicaid, 11 (14%) Medicare, and 10 (13%) were private insurance. In 2000, there were 3 (12%) patients with stage 0 disease, 5 (21%) with stage I; 9 (37.5%) with stage II, and 7 (29%) with stage III. In 2008 there were 28 (36%) patients with stage 0 disease, 15 (19%) with stage I, 17 (22%) with stage II, and 18 (23%) with stage III (Figure 2).

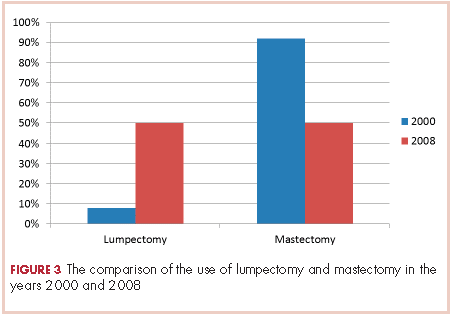

None of those values are statistically different. In 2000, 2 of the 24 patients had lumpectomies (partial mastectomy) and the rest had mastectomies. In 2008, 39 (50%) patients had mastectomy and 39 (50%) had lumpectomies (Figure 3). This was a statistically significant difference.

Radiation was given to both patients with lumpectomy in the 2000 group. In the 2008 group, all patients with lumpectomies were evaluated for radiation, and 6 of them did not receive radiation for the following reasons: 3 had very small foci of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) and were treated with hormone therapy and no radiation; 1 patient had a lumpectomy for stage 1 cancer and also did not get radiation therapy because of a low oncotype and very small lesion; 2 patients were older than 70 years and had DCIS and were treated with tamoxifen alone as per NCCN Guidelines for women in that age group. The rest of the patients with lumpectomies received postoperative radiation.

Hormone and HER2 (human epidermal growth factor receptor 2) status was obtained on all patients. For the 2000 patients, 71% had 1 hormone receptor–positive (estrogen receptor [ER] or progesterone receptor [PR]), 21% were triple negative (ER-PR and HER2-neu), and 42% had HER2-neu–positive tumors. For the 2008, patients 65% were positive for 1 hormone receptor (ER or PR), 28% were triple negative (ER-PR and HER2-neu), and 7% had HER2-neu-positive tumors.

All patients were offered chemotherapy and hormone therapy if appropriate, as per NCCN guidelines. If a patient’s tumor was found to be HER2-positive, then the chemotherapy regimen would include the use of trastuzumab in both groups.

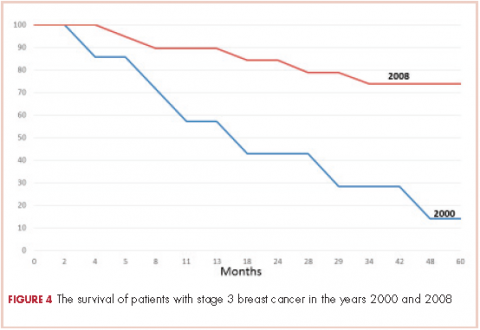

The 5-year survival for the 2008 stage III patients was 73.7%, compared with 14.2% for the 2000 stage III patients. The only deaths in the 2008 group were in patients with stage III disease. In the 2000 group, 4 of the 5 patients with stage III cancer died, and 33% of patients with stage I or II either died or were lost to follow-up before 5 years. This survival difference is significant by a chi-square and Wilcoxon analysis, with a P value of .01.

In 2000, 86% of patients with cancer were termed self-pay, that is, they had no insurance and they were not converted to emergency Medicaid. In 2008, 16% of patients were self-pay, and the rest were converted to Medicaid. In 2000, fewer than 2% of patients had commercial insurance, compared with 9% in 2008.