Hemophilia A and B: An Overview

INHIBITORS TO FACTOR IX

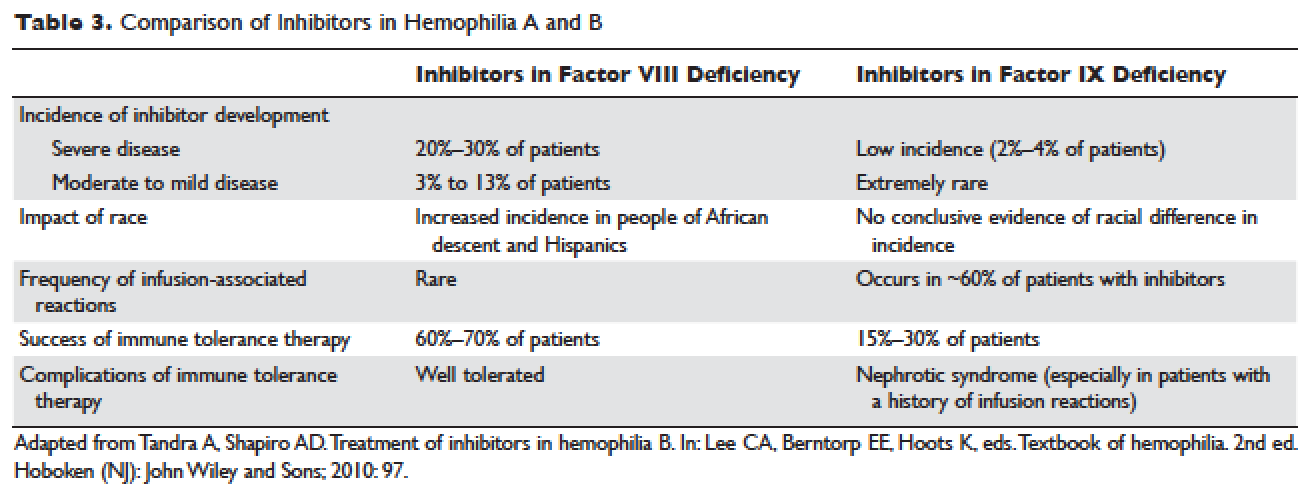

Factor IX inhibitors are relatively uncommon, occurring in only 1% to 3% of persons with hemophilia B. This is in striking contrast to hemophilia A, where approximately 30% of patients develop inhibitors. The majority of patients with hemophilia B who develop inhibitors have severe hemophilia B.

Risk Factors

Certain mutations in the factor IX gene are associated with an increased incidence of inhibitor development. Large deletions and frame-shift mutations leading to the loss of coding information are much more likely to be associated with inhibitor development. Large deletions account for only 1% to 3% of all hemophilia B patients, but account for 50% of inhibitor patients.68 Patients with hemophilia B who develop inhibitors are at risk for developing anaphylactic reactions to factor IX–containing products. Anaphylaxis occurred more frequently in families with null mutations (large deletions, frame-shift mutations, or nonsense mutations) than in those with missense mutations.69 With hemophilia A, approximately 40% to 50% of black individuals develop inhibitors, but no such association has been found in hemophilia B. Individuals who develop an inhibitor to factor IX do so relatively early in life (within the first 4 to 5 years), after a median of 9 to 11 exposure days to any factor IX–containing products. Because of the severity of a potential anaphylactic reaction occurring early in life after very few exposures to factor IX, all infants and small children with severe hemophilia B should be closely followed over their first 10 infusions with any factor IX–containing products in a facility equipped to treat anaphylactic shock.70–72 A comparison of inhibitors in hemophilia A and B is shown in Table 3.

,

TREATMENT OF ACUTE BLEEDS IN PATIENTS WITH FACTOR VIII INHIBITORS

The available therapeutic agents for treatment of acute hemorrhage in children with hemophilia A with an inhibitor include high-dose recombinant or plasma-derived factor VIII concentrate, activated prothrombin complex concentrates (aPCCs), and recombinant activated factor VII (rFVIIa). In addition, antifibrinolytics may be used as an adjunct therapy.

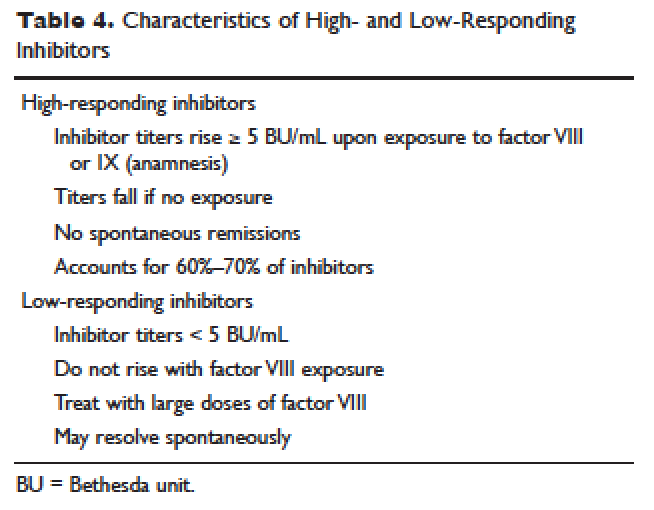

Patient response to each treatment varies widely, with some patients responding well to one treatment and less well to another. Neither the patient's history nor standard lab tests can assist in making the best choice for the patient. A personalized approach to factor selection is used, and the dosing of that particular agent is often determined primarily by clinical assessment. Inhibitors are quantitated using the Bethesda inhibitor assay and clinically are classified as low- and high-responding inhibitors (Table 4). Inhibitor screening should be done prior to invasive procedures and periodically during the first 50 days of treatment since the risk for inhibitor development is highest during this period.

Low-Responding Inhibitors

A low-responding inhibitor is one in which inhibitor titers are < 5 Bethesda units (BU)/mL; patients with low-responding inhibitors can generally be treated with factor VIII concentrates at higher doses.73 Because the effect of factor VIII inhibitor is usually delayed, the Bethesda titer in plasma is determined after a 2-hour incubation period. As a result of this time delay, continuous administration of factor VIII is usually found to be effective.74 For a serious limb- or life-threatening bleeding episode, a bolus infusion of 100 IU of factor VIII per kg of body weight is administered, and the level is maintained by treatment at a rate of 20 IU/kg/hr. An assay for factor VIII should be performed 1 hour after the bolus infusion and at least daily thereafter. As the antibody titer drops, the daily level of factor VIII may rise and thus downward adjustment of the continuous infusion rate may be required. For routine joint and muscle hemorrhage, patients can usually be managed with infusions at twice the usual dosage. Routine inhibitor assays should be performed after exposure to factor VIII to determine whether an anamnestic response has occurred.

High-Responding Inhibitors

Most clinicians caring for patients with limb- or life-threatening bleeding episodes prefer to use products for which therapeutic levels can be monitored. As described earlier, continuous admin-istration of factor VIII is often effective because of the time delay in inhibition by the antibody. An initial dose of 100 to 200 IU/kg can be administered, and factor VIII levels can be determined 1 hour after initiation of continuous infusion at a rate of 20 to 40 IU/kg/hr. If a factor VIII level cannot be obtained (ie, patients with inhibitor titers > 5 to 10 BU/mL), alternative approaches include the bypassing agents aPCC and rFVIIa.

First used in the 1970s, aPCCs represented a significant improvement in the management in patients with hemophilia with inhibitors. They contain multiple activated serine protease molecules; activated factor X and prothrombin are the main active components in FEIBA (factor eight inhibitor bypassing activity), the most commonly used aPCC in the United States. FEIBA is a pooled plasma product that contains activated factors II, VII, IX and X, and has a duration of action of about 6 to 12 hours. For treatment of acute bleeds, the recommended dose of FEIBA is 50 to 100 IU/kg infused every 8 to 12 hours (maximum daily dose of 200 IU/kg). There is a risk of thrombosis/disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) with very large doses given frequently (> 200 IU/kg/day).

rFVIIa directly activates factor X and increases thrombin production on the surface of activated platelets in the absence of factor VIII or factor IX. Standard dosing of rFVIIa is 90 to 120 µg/kg, and many hemophilia treatment centers use higher doses (270 µg/kg/dose), especially in children and young adults. The half-life is about 1.5 to 3 hours, and therefore frequent administration (every 2–6 hours) is required. In one study that assessed the safety and efficacy of fixed-dose rFVIIa in the home setting, hemostasis was achieved in 566 (92%) of evaluable bleeding episodes, and following administration of the additional maintenance dose, hemostasis was maintained in 95% of successfully treated cases.75 As with aPCCs, there is no standardized quantitative laboratory test for measuring the effectiveness of rFVIIa therapy.

All currently used bypassing agents are associated with a risk of thrombotic complications including thromboembolism, DIC, and myocardial infarction. These complications are very rare in patients with hemophilia, however. In general, bypassing agents work for most bleeds and for most patients, but are not as predictable as factor replacement therapy and cannot be monitored by laboratory assays.