Thrombosis in Pregnancy

CASE PRESENTATION 3

A 25-year-old woman is diagnosed with antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) during her second pregnancy when she experiences fetal loss during her second trimester. Pathologic examination of the placenta reveals infarcts. Laboratory evaluation reveals positive high-titer anticardiolipin and anti-beta-2 glycoprotein 1 antibodies (IgG isotype) and lupus anticoagulant on 2 separate occasions 12 weeks apart. In a subsequent pregnancy, she is started on prophylactic LMWH and daily low-dose aspirin (81 mg). At 36 weeks’ gestation, she presents with a blood pressure of 210/104 mm Hg and a platelet count of 94,000 cells/µL. She is diagnosed with preeclampsia and hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets (HELLP) syndrome and is induced for early delivery. About 2 weeks after vaginal delivery, she notices shortness of breath and chest pain. A CTPA demonstrates a right lower lobe lobar defect consistent with a PE. Her anticoagulation is increased to therapeutic dosage LMWH.

To what extent does thrombophilia increase the risk for VTE in pregnancy?

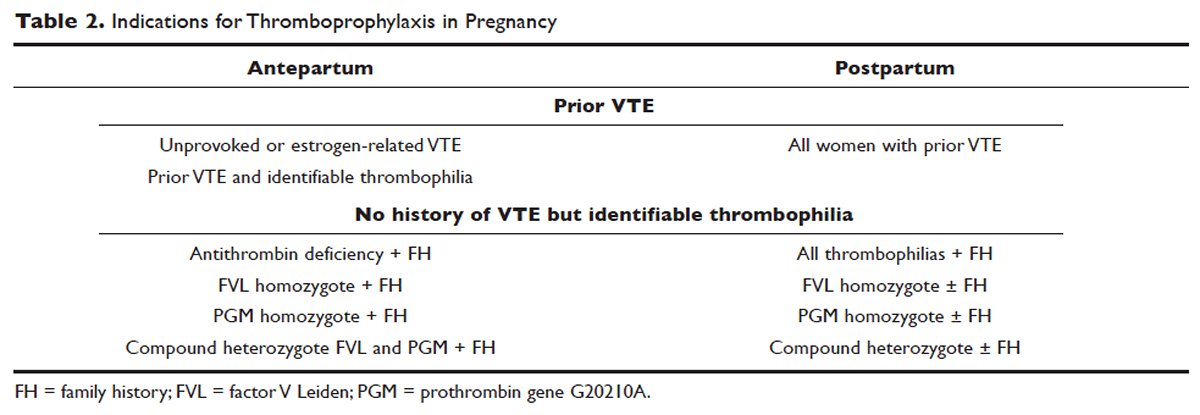

Approximately 50% of pregnancy-related VTEs are associated with inherited thrombophilia. A systematic review of 79 studies, in which 9 studies (n = 2526 patients) assessed the risk of VTE associated with inherited thrombophilia in pregnancy, revealed that the odds ratio for individuals with thrombophilia to develop VTE ranged from 0.74 to 34.40.73 Although women with thrombophilia have an increased relative risk of developing VTE in pregnancy, the absolute risk of VTE remains low (Table 1).41,73,74

,

How is APS managed in pregnant patients?

Women with history of recurrent early pregnancy loss (< 10 weeks’ gestation) related to the presence of aPL antibodies are managed with low-dose aspirin and prophylactic-dose UFH or LMWH. This treatment increases the rate of subsequent successful pregnancy outcomes and reduces the risk for thrombosis. A 2010 systematic review and meta-analysis of UFH plus low-dose aspirin compared with low-dose aspirin alone in patients with APS and recurrent pregnancy loss included 5 trials and 334 patients. Patients receiving dual therapy had higher rates of live births (74.3%; relative risk [RR] 1.30 [CI 1.04 to 1.63]) compared to the aspirin-only group (55.8%).75 A 2009 randomized controlled trial compared low-dose aspirin to low-dose aspirin plus LMWH in women with recurrent pregnancy loss and either aPL antibodies, antinuclear antibody, or inherited thrombophilia. The study was stopped early after 4 years and found no difference in rates of live births between the groups (77.8% versus 79.1%).76 However, a randomized case-control trial of women with aPL antibodies and recurrent miscarriage found a 72% live birth rate in 47 women randomly assigned to low-dose aspirin and LMWH.77 A 2012 guideline from the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) recommends that women with aPL antibodies with a history of 3 or more pregnancy losses receive low-dose aspirin plus prophylactic-dose LMWH or UFH.78 A 2014 systematic review and meta-analysis showed that the combination of low-dose aspirin and UFH resulted in a higher live-birth rate than aspirin alone in 803 women with APS (RR 1.54 [95% CI 1.25 to 1.89]).79 Further large randomized controlled trials are needed to confirm optimal management of recurrent miscarriage and aPL antibodies.

The addition of prednisone to aspirin, heparin, or both has shown no benefits in pregnant women with aPL antibodies. Indeed, prolonged use of steroids may cause serious pregnancy complications, such as prematurity and hypertension.80–83 Intravenous infusions of immunoglobulin (IVIG) have not been shown to be superior to heparin and aspirin. This finding was confirmed in a multicenter clinical trial that tested the effects of IVIG compared with LMWH plus low-dose aspirin for the treatment of women with aPL antibodies and recurrent miscarriage. The rate of live-birth was 72.5% in the group treated with heparin plus low-dose aspirin compared with 39.5% in the IVIG group.84

Preeclampsia and HELLP syndrome complicated the case patient’s pregnancy even though she was being treated with prophylactic-dose LMWH and low-dose aspirin, the current standard of care for pregnant women with APS (UFH can be used as well). It is important to note that complications may still occur despite standard treatment. Indeed, PE is more common in the postpartum than in the antepartum period. Prompt diagnosis is paramount to initiate the appropriate treatment; in this case the dose of LMWH was increased from prophylactic to therapeutic dose. However, additional therapeutic modalities are necessary to improve outcomes. A randomized controlled trial comparing standard of care with or without hydroxychloroquine is under way to address this issue.

PROPHYLAXIS

CASE PRESENTATION 4

A 34-year-old woman G1P0 at 6 weeks’ gestation with a past medical history of a proximal lower extremity DVT while on oral contraception is treated with warfarin anticoagulation for 6 months. Her obstetrician consults the hematologist to advise regarding antithrombotic management during this pregnancy.

What is the approach to prophylaxis in women at high risk for pregnancy-associated VTE?

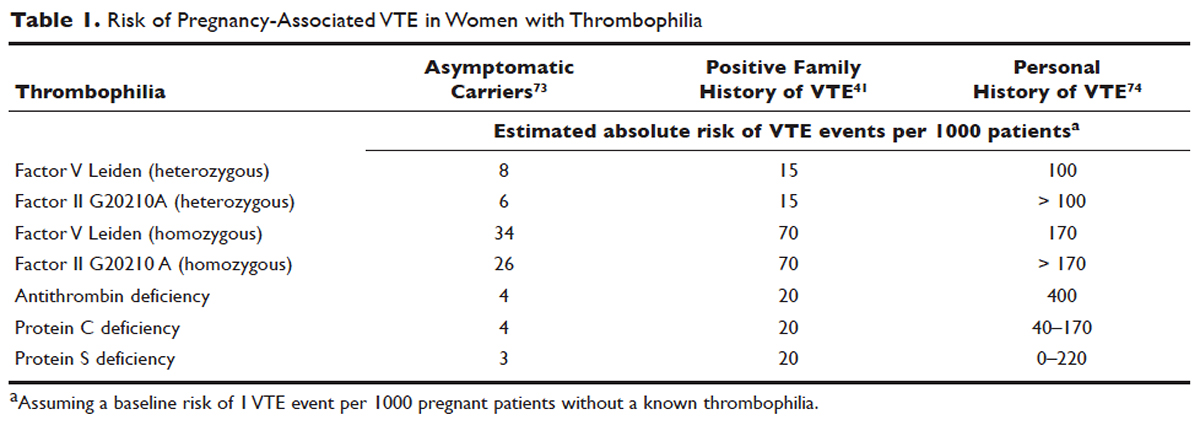

All women at high risk for pregnancy-associated VTE should be counseled about the signs and symptoms of DVT or PE during preconception and pregnancy and have a plan developed should these symptoms arise. The ACCP guidelines on antithrombotic therapy outline recommendations ranging from clinical vigilance to prophylactic and intermediate-dose anticoagulation, depending on the risk for VTE recurrence, based on the personal and family history of VTE and type of thrombophilia (Table 2).78 These recommendations range from grade 2B to 2C.