Navigating NAFLD: Unveiling the approach to mitigate the impact of NAFLD

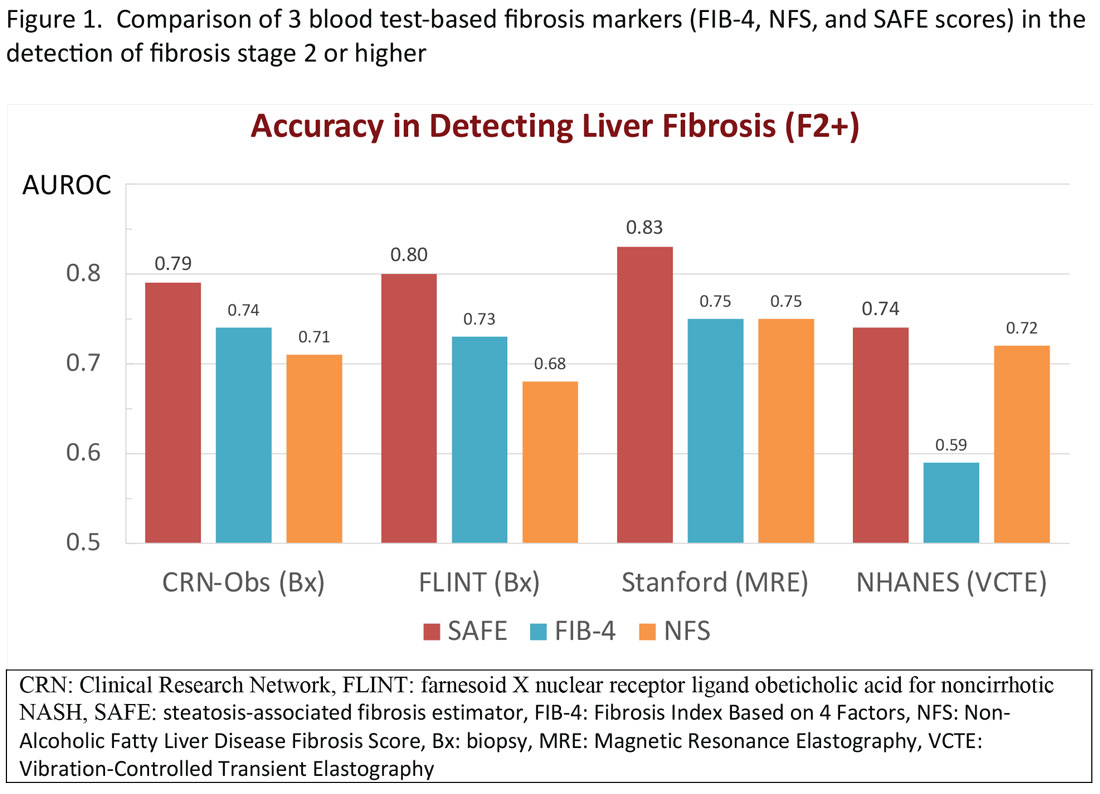

In general, these elastographic tests are not readily accessible to most physicians outside hepatology specialty practices. Instead, blood test-based markers have been developed and widely recommended as the initial modality to assess liver fibrosis. Figure 1 represents a partial list of blood test-based markers. Traditionally, FIB-4 and NFS have been considered the most widely recommended by society guidelines. The AGA Pathway for evaluation of patients with NAFLD recommends first to apply the FIB-4 score and, in patients considered to be at intermediate risk of fibrosis for advanced fibrosis (stage 3 or 4, FIB-4 = 1.3-2.67), to assess liver stiffness by VCTE.14

More recently, the accumulating natural history data have highlighted the inflection in the risk of future outcomes coinciding with F2 and therapeutic trials that target patients with “at risk NASH,” thus more attention has been paid to the identification of patients with stage 2 (or higher). The steatosis-associated fibrosis estimator (SAFE) was developed for this specific purpose. The score has been validated in multiple data sets, in all of which SAFE outperformed FIB-4 and NFS (Figure 1). When the score was applied to assess overall survival in participants of the NHANES, patients with NAFLD deemed to be high risk (SAFE > 100) had significantly lower survival (37% Kaplan-Meier survival at 20 years), compared to those with intermediate (SAFE 0-100, 61% survival) and low (SAFE < 0, 86% survival). In comparison, the 20-year survival of subjects without NAFLD survival was 79%.15

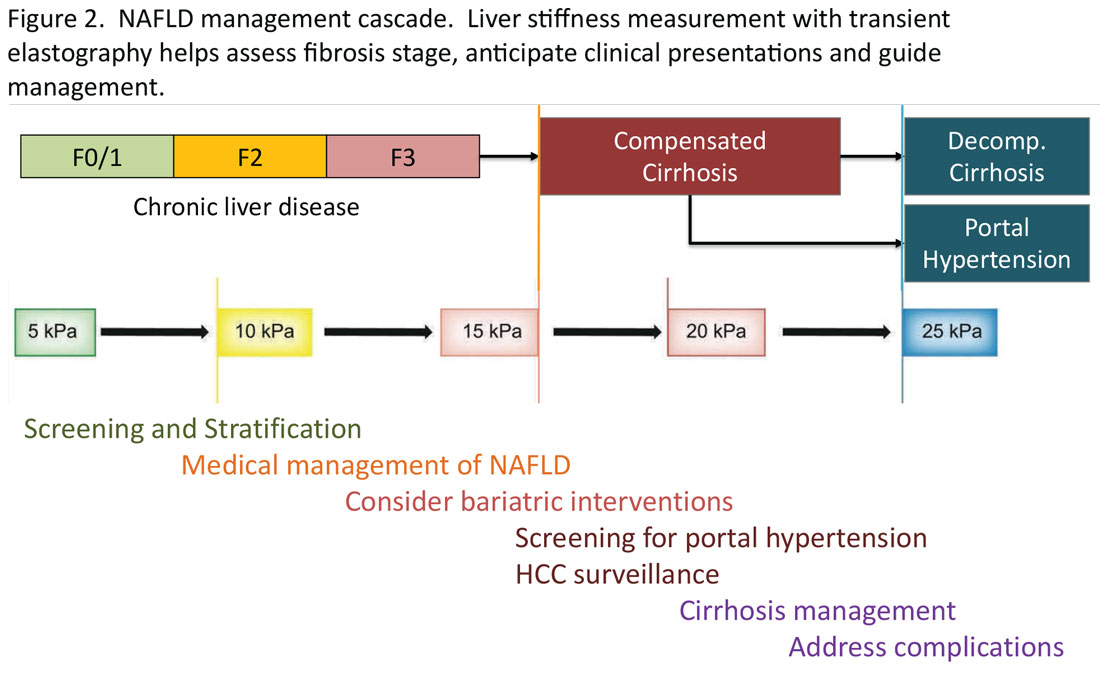

Regardless of the modality for initial stratification, it is widely accepted that mechanical elastography constitutes the next step in prognosticating the patient. In the AGA Pathway, liver stiffness of < 8 kPa is considered low risk, which corresponds in most analysis with lack of stage 2 fibrosis, whereas stiffness of > 12 kPa may be indicative of stage 3 or 4. These recommendations are consistent with those from the latest Baveno Consensus Conference (“Baveno 7”). Figure 2 expands on the so-called “rule of 5” from the consensus document and correlates liver stiffness (by VCTE) with progression of liver fibrosis as well as clinical presentation. For example, liver stiffness < 15 kPa is associated with a low risk of clinically significant portal hypertension (CSPH). Similarly, in patients with a normal platelet count (>150,000/mm3) and liver stiffness < 20 kPa, the probability of gastroesophageal varices is sufficiently low that a screening endoscopy may be avoided. On the other hand, liver stiffness > 25 kPa is associated with increasing risk of decompensated cirrhosis and portal hypertension.16

Partnership between primary care and specialty

The insights expressed in Figure 2 can be utilized to guide management decisions. In patients without evidence of liver fibrosis, emphasis may primarily be on screening, stratification and management of metabolic syndrome. For patients with evidence of incipient liver fibrosis, medical management of NAFLD needs to be implemented including lifestyle changes and pharmacological interventions as appropriate. For patients unresponsive to medical therapy, an endoscopic or surgical bariatric procedure should be considered. Management of patients with evidence of cirrhosis includes screening for portal hypertension, surveillance for HCC, medical management of cirrhosis, and finally, in suitable cases, referral for liver transplant evaluation. The reader is referred to the latest treatment guidelines for detailed discussion of these individual management modalities [ref, AGA and AASLD guidelines].14,17