Critical Care in the ED: Mechanical Ventilation, Sepsis, Neurological Hypertensive Emergencies, and Pressors in Shock

The tremendous overlap between the specialties of emergency medicine and critical care medicine is particularly apparent in the initial resuscitation of critically ill patients—a vulnerable population in which the early period of care has significant impact on outcomes.

In summary, assuming control of a patient’s respiratory system—with its nuanced and responsive role in acid-base, oxygenation, and cardiopulmonary hemodynamics—is one of the most difficult situations routinely encountered by an EP. While the procedure itself may be life-saving, the next several hours can have significant impact on the patient’s long-term outcome.

Treating Sepsis and Surviving Sepsis: Recommendations Versus the ARISE/ProCESS Trials

Sepsis and Septic Shock

,Sepsis is defined as an infection plus systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS). Severe sepsis is sepsis plus sepsis-induced organ dysfunction or tissue hypoperfusion resulting in or caused by lactic acidosis, acute lung injury, altered mental status, or coagulation abnormalities. Septic shock refers to persistent sepsis-induced hypotension despite adequate fluid resuscitation.24 The ambiguity of these definitions may invariably lead to a practitioner’s underappreciation or misconception of the importance of sepsis.

Sepsis is one of the most common, yet least-recognized, entities. In the United States, it is estimated that 3 in 1,000 people annually are affected by sepsis, and every few seconds, a person dies of sepsis.25 Both numbers underestimate the effects on the elderly. Clinical manifestations of sepsis vary, and the condition may originate from both community-acquired and healthcare-associated sources.

In 2001, a landmark study demonstrated that early goal-directed therapy (EGDT) reduced mortality and improved patient outcomes in patients presenting to the ED in severe sepsis.26 The estimated 12% to 16% reduction in mortality reported in this trial began an initiative to broaden the scope and awareness of sepsis.

Current Literature and Evidence-Based Guidelines

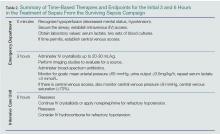

The most recent guidelines for the management of septic shock from the Surviving Sepsis Campaign are summarized in Table 1. With its last revision, the Surviving Sepsis guidelines of 2012 has two main management foci—initiating treatment within the first 3 and the first 6 hours after recognition within the first 3 hours and those within the first 6 hours after sepsis recognition (Table 2). Within the first 3 hours, the treatment team should draw a serum lactate level; obtain cultures prior to the administration of antibiotics; initiate broad-spectrum antibiotics as early as possible; and administer 20 to 30 mL/kg of crystalloid fluids in patients with hypotension or a lactate level greater than 4 mmol/L. Within the first 6 hours, the clinician should administer intravenous (IV) vasopressors, preferentially norepinephrine, for persistent hypotension after a fluid challenge to maintain a mean arterial pressure >65 mm Hg; place a supra-diaphragmatic central venous catheter to measure a serum mixed venous O2 saturation (ScvO2) and central venous pressure (CVP); and measure serial serum lactate levels if they were initially elevated (lactate ≥4 mmol/L [36 mg/dL]).24,30,31 The targets for ScvO2 and CVP are ≥70%, and >8 mm Hg, respectively.

Summary

Sepsis is a prevalent ED presentation associated with mortality that can present in a complex fashion. Early recognition and management is essential and can be condensed into a few key recommendations. Becoming familiar with and incorporating these recommendations into daily practice will enable EPs to deliver quality care to every patient presenting with sepsis, and will also reduce mortality.