EARLY LIFE STRESS AND DEPRESSION Childhood trauma may lead to neurobiologically unique mood disorders

Adults with a history of child abuse or neglect may respond differently than other depressed patients to the usual treatments.

A distinct ‘ELS depression’?

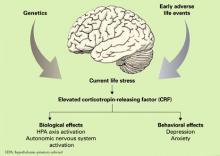

Depression has a complex etiology based on interacting contributions from genes and the environment19 that may ultimately result in biologically and clinically distinct forms of depression.20 Exposure to stress, particularly during neurobiologically vulnerable periods of development, may be one means whereby the environment influences the development of depression in genetically susceptible individuals.21

Heredity. Kendler and colleagues22 studied 1,404 female adult twins and observed that childhood sexual abuse was associated with both an increased risk for major depression and a marked increased sensitivity to the depressogenic effects of stressful life events. Moreover, research in human gene-environment interactions has identified a functional polymorphism in the promoter region of the gene for the serotonin transporter which appears to moderate the influence of stressful life events on the development of depression and potential for suicide.23,24

Environment. Similarly, a key variable in determining the clinical outcome of childhood trauma may be the developmental timing of the abuse. Women abused before age 13 are at equivalent risk for developing PTSD or major depressive disorder (MDD), whereas women abused after age 13 are more likely to develop PTSD.25

Thus a major challenge in depression research is to understand the biological mechanisms that mediate the effects of trauma during development through the genetic windows of vulnerability and resilience.

Animal models of ELS have been studied to elucidate the neurobiological consequences of early life trauma in adult humans. This work has largely been performed in rodents and nonhuman primates using a variety of experimental paradigms.

Although a comprehensive review of these data is beyond the scope of this article, ELS in laboratory animals has consistently been found to produce both short- and long-term adverse neurobiological and endocrine effects as well as cognitive dysfunction and abnormal behavior.21 One possible mechanism mediating these effects is a persistent hyperresponsiveness of different components of the HPA axis following exposure to stress.

Studies in adult women have sought to uncover the long-term effects of ELS (prepubertal physical or sexual abuse) on reactivity of the HPA axis in response to the Trier Social Stress Test, a standardized psychosocial stress test.26 It consists of the subject giving a 10-minute speech and performing a mental arithmetic task in front of a panel of stern-appearing evaluators. Variables measured include heart rate, plasma ACTH, and cortisol concentration at intervals before and after the performance component of the test. The four groups in this study included:

- women without psychiatric illness or history of ELS serving as a control group (CON)

- depressed women without a history of ELS (non-ELS/MDD)

- depressed women with a history of ELS (ELS/MDD)

- non-depressed women with a history of ELS (ELS/non-MDD).

The largest ACTH and cortisol responses and increases in heart rate following this stress exposure were seen in the ELS/MDD group. In fact, the ACTH response of these women was more than 6 times greater than that observed in the control group. The ELS/MDD group of women also had greater rates of comorbid PTSD (85%) in comparison to the other experimental groups as well.

These data are consistent with the hypothesis that ELS produces enduring sensitization of the HPA axis and autonomic nervous system response to stress. This phenomenon may constitute an important etiological element in the development of stress-related adult psychiatric illnesses such as depression or PTSD.

To further explore the hypothesis that ELS alters set points of the HPA axis, we sought to characterize the effects of standard HPA axis challenge tests (CRF stimulation test and ACTH1-24 stimulation test) in a similar population of women.27 Depressed women with a history of ELS and depressed women without a history of ELS both exhibited a blunted ACTH response to infusion of exogenous CRF. Conversely, women with a history of ELS but without current depression had an increased ACTH response following CRF infusion.

With respect to the ACTH1-24 stimulation test, abused women who were not depressed had lower plasma cortisol levels at baseline and after administration of ACTH1-24. Similar to the findings of our previous study,26 women with MDD and a history of ELS were more likely to report current life stress and to also have comorbid PTSD than women with ELS who were not depressed. Blunting of the ACTH response to exogenous CRF in depressed women with a history of ELS may in part be secondary to acute downregulation of pituitary CRF receptors as a result of chronic CRF hypersecretion.

More recently, Carpenter and colleagues28 evaluated the relationship between the perception of ELS and CSF CRF in patients with depression and healthy control subjects. The perception of ELS predicted CSF CRF concentration independent of the presence or absence of depression. Further, and most interestingly, the developmental timing of the stress exposure was predictive of either relatively increased or decreased CSF CRF. ELS before age 6 was associated with elevated CSF CRF, whereas perinatal and preteen exposure to stressful events was associated with decreased CSF CRF.